LEGAL

WHAT DOES NOT KILL US

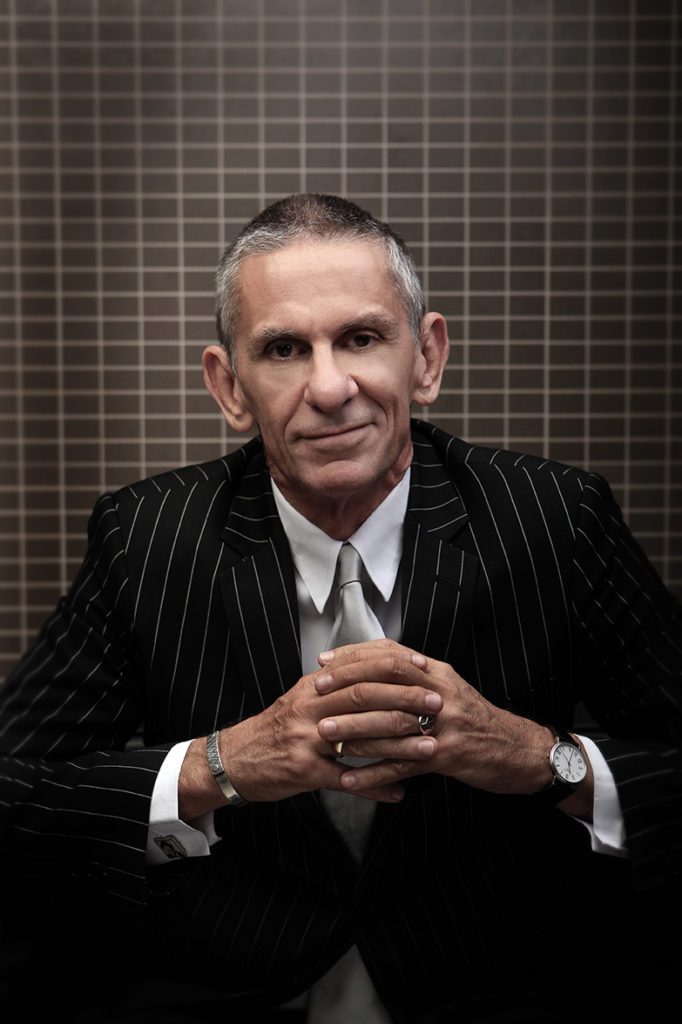

WORDS: Chris Nyst PHOTOGRAPHY Brian Usher - www.usherusher.com

The renowned 19th-century philosopher and poet Friedrich Nietzsche once said: “That which does not kill us makes us stronger.” That observation is perhaps as true today as it ever was.

A little over a year ago, we were faced with the scary prospect that a cataclysmic pandemic was set to sweep the globe. On February 11, 2020, the World Health Organisation named the disease “COVID-19” – an acute respiratory syndrome with potentially fatal consequences. The first reported death occurred in Wuhan, China, on January 9, 2020; the first outside China in the Philippines on February 1, 2020; and the first outside Asia in the US on February 6, 2020. Suddenly, the world was poised on the edge of a terrifying precipice, an unknown future ahead.

Now, a year later, there are around 110 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 in 219 countries and territories around the world. International borders have closed and the virus has killed more than 2.4 million people to date.

But that’s not the whole story. Of all those diagnosed as contracting the virus, more than 95 per cent have fully recovered. And now, with a virus in place, the world has begun to fight back.

So what have the past 12 months taught us about ourselves, the survivors, so far? How have we coped with the fear, and the reality, of COVID-19? In seeking to answer that question, some psychologists have drawn on the lessons of history to make some interesting observations.

During the early days of World War II, Nazi Germany launched a sustained, nine-month bombing attack on the British populace that became known as ‘The Blitz’. On September 6, 1940, Adolf Hitler ordered a ‘blitzkrieg’ – the German word for ‘lightning war’ – on Britain and for the next 57 days, London was systematically bombed, day and night, by the German Luftwaffe. In unrelenting carpet air raids, the Luftwaffe rained bombs down on industrial and civilian targets in towns and cities throughout the United Kingdom.

The ensuing conflagration was designed to drive fear and panic into the civilian population, to demoralise the Brits and sap their national will to resist the then seemingly unstoppable forces of the Third Reich. Fearing mass panic on the streets of London, Churchill’s government rushed to set up psychiatric hospitals to cope with the expected widespread mental health fall-out.

As it turned out, it didn’t happen. Despite nine months of sustained bombing by the Luftwaffe, 43,000 civilians killed, 139,000 more wounded and more than a million houses destroyed, the predicted chaos on the streets of Britain never materialised. No psychiatric crisis emerged, even during the most intense period of bombing in September 1940.

Brits carried on with their everyday lives, referring to the air raids as if they were weather, a day of particularly heavy bombing being described as ‘very blitzy’. The phenomenon was so unexpected it moved one American commentator of the day to observe: “By every test and measure, these people are staunch to the bone… The British are stronger and in a better position than they were at its beginning.”

The special network of psychiatric clinics opened to receive mental casualties of the attacks were soon closed due to lack of demand.

At the time, the eminent Canadian psychiatrist John Thompson MacCurdy was teaching psychopathology at Cambridge University, where he lectured soldiers about being sent into combat on the psychology of fear. The Blitz experience in London inspired MacCurdy to write his 1943 treatise, The Structure of Morale. In it, he applied the principles of conditioned response to the emotion of fear in persons untouched by the bombing attacks, dividing the targeted Londoners into three separate categories – direct hit, near miss and remote miss.

The direct hit group he defined as those killed in the bombings. The near miss category referred to those who were wounded in some way, or who had loved ones killed, and the remote miss cohort were those who faced serious fear, but survived.

In studying the effect of the bombings on community morale, MacCurdy observed of the first group – those classed direct hit: “The morale of the community depends on the reaction of the survivors … Put this way, the fact is obvious. Corpses do not run about spreading panic.”

Of course, the victims’ deaths no doubt had a deep and direct effect on others, particularly in the near miss group. However, with 139,000 Londoners wounded, out of a city of 8 million people, the near miss group were a relatively small minority.

The overwhelming majority of those affected by The Blitz fell into the third group, remote miss – those who had faced the terror of the bombing onslaught, but had survived. Of that significant majority, MacCurdy opined that the process of facing serious fear without having panicked or been harmed had led to ‘a feeling of excitement with the flavour of invulnerability’. Instead of producing a city of millions running in fear and panic, The Blitz had left Londoners feeling invincible.

In the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic, fears were raised of essential supplies drying up, economies collapsing, and health systems becoming overwhelmed by the weight of demand. However, as things have transpired, even in the most hard-hit communities, the majority of citizens have not suffered a direct physical impact from the disease. With an estimated infection/fatality rate of less than one per cent, and a relatively high rate of asymptomatic infection, COVID-19 has left an overwhelming majority of people in the remote miss category.

Like the Londoners of World War II, those of us in the remote miss category may be feeling a tad invulnerable. Certainly, so far at least, COVID-19 has not killed us. Hopefully, as Nietzsche predicted, it will ultimately make us stronger.

Author – Chris Nyst