PEOPLE

The scars of sound

WORDS: PHOTOGRAPHY

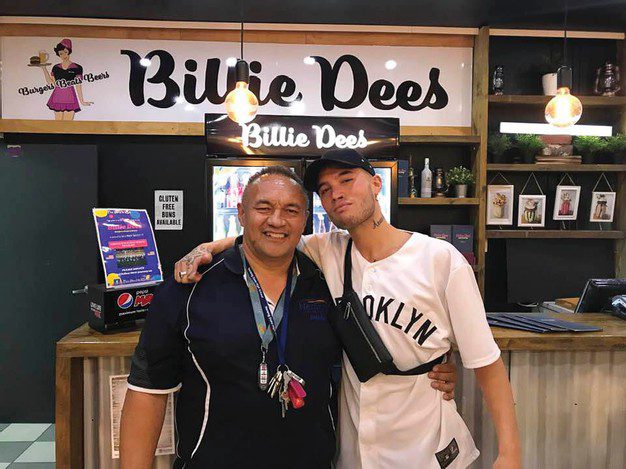

Magic is happening in the music rooms of Australian schools. Specifically, there had been magic occurring at Nerang State High School — thanks to Dean Hawawira. And if you’ve never heard of him or his music, ORM is here to fill you in.

Shakespeare wrote, ‘If music be the food of love, play on; Give me excess of it, that surfeiting…’

From the very beginning back in New Zealand, Dean Harawira has been serving excess of it, surfeiting our appetite for music with only success in mind. That’s one of the many gifts he garnishes on to the plates of new talent and his dedicated students who form part of his music class at Nerang State High School.

You are excused if you do not recognise his name, nor associate him with being a key influencer on the Australian music scene. However, that is exactly what this 53-year-old high school music teacher is, until recently plying his trade in classrooms on a daily basis — and he recently earned himself a nomination with the music elite and the Australian ARIA awards.

Harawira has been embossing the envelope of talented musicians on the Gold Coast and in New Zealand for the past 35 years, quietly slipping through the velvet curtains himself without too much fanfare or recognition.

His story was shaped in the small coastal community of Wainuiomata in New Zealand, a community outlined in chalk, set among a similar disposition to the Once Were Warriors movie — with high unemployment and a lower socioeconomic demographic, the entire region bleeds rugby and passion, boasting a tough interior landscape. With little else to do, the area is welded in spirit and a sense of community, a courthouse of instinct and naturalism.

Harawira learnt his street smarts sitting around the burning 44-gallon barrels fuelled by pine pallets and cardboard, with a four-string guitar in one hand and preparing the traditional hangi feast with the other.

It is easy to lose the road map out of this town and one day find yourself sitting at the table next to another wasted talented someone. The world is full of talented derelicts, people that are blessed with freakish natural gifts, sadly there is a portion of the Maori culture who will never get the opportunity to display their talents and share their gifts with us.

Harawira was different. He was gritty and determined to make a pay cheque out of music. Being a full-time musician in those days was rare, and to do it, one would be ridiculed and would have to suffer for their art to even contemplate going to Woolworths with a shopping list.

His old-school punch-through style prepared him well for the disappointments of the industry that lay ahead for him — the days and nights that he toiled with the highs and lows, the rejection, the failures for his hard work and effort, the loss of his marriage, the pain surrounding the death of family and friends.

Harawira was bridled with a solid girth and always found strength in living a minimalistic life, taking on each situation as penance for starting this journey, all those years before. He learnt to inhale his experiences and not hold his breath. He credits his humility today to those dark days in the lower basement of music.

***

Dean Harawira is a musical icon 30 years in the making, and we as the general public only get to see the ‘overnight’ part of the success story. The driving vehicle for his success has been in adapting old ideas of music to the platforms of the modern age and transcending the status quo of what we believe music and teaching to be.

Harawira initially struggled with music as a child until the process of teaching himself grew into a fascination and love affair with funk, R&B, and reggae. Otherwise a typical kid and talented representative footballer with a bit of a rebel streak, he would often entertain for his friends and family with comical impersonations of artists and songs of the day.

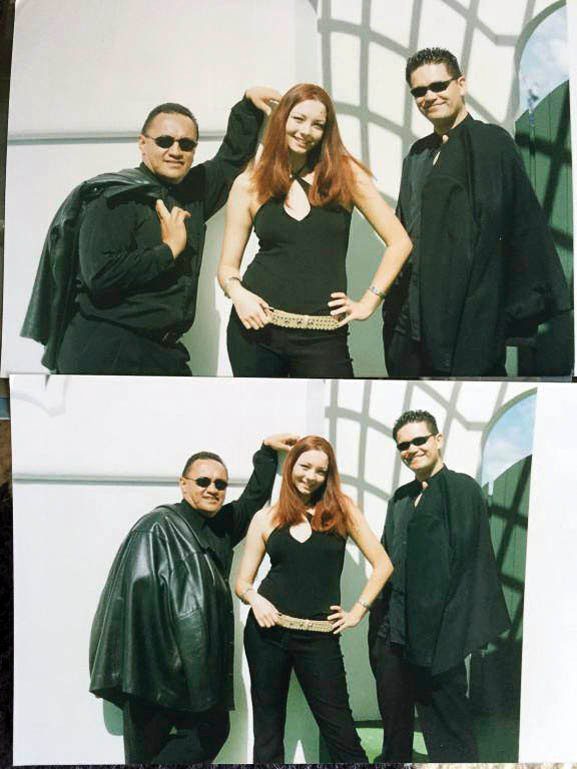

Musically gifted, he found himself in a series of bands in New Zealand and then on the Gold Coast, moving here in 1988 from Wellington. In his early 20s, he found himself working on the Island Queen showboat out of Tiki Village, playing guitar and leading the Island Queen Polynesian show through nightly tours around the Broadwater of the Gold Coast, finally landing a semi-permanent performance gig that brushed his creative juncture and gave him satisfaction.

I first met Dean on this showboat, performing the Island Queen cabaret show, where he would take requests from the audience and adapt whatever contemporary song or golden oldie they suggested with humour and creativity. He was a master of impersonation and often satirically took off Stevie Wonder, Elvis Presley, and Tom Jones (to name a few), soaking up the adulation of the live performance like a drug, then afterwards, venturing out to piano bars and other local gigs until sun-up. He was self-mutilating himself with this pursuit, chasing some resemblance of the stigma that surrounded the ‘rock star life’.

“The contrast between the highs of a successful show and the anti-climactic low that often follows can be hard to adjust to,” he reveals, “a phenomenon that has been termed ‘post-performance depression’ — the ups and downs of life. It was destructive on me, that’s for sure. I’d come home from a gig and I’m back to feeding the cat.

“There was a lot of tension, because I’m thinking to myself, ‘I don’t deserve this; I’m a big star’, and that was one of the contributing factors in ending my marriage. You end up with a lot of expectations from life that aren’t real or always fulfilled in everyday tasks like going down to the shops for milk or even going for dinner with friends. It’s hard to replace all that adrenaline.”

Living the life of a full-time muso, with no money, a short fiery temper, and sleeping ’til midday, the days would roll into nights. Music was his oxygen — without it, he would reach deep dark places of depression, pushing on for days without rest, fuelled by whiskey, cigarettes, drugs, and a bass guitar.

I remember sharing a beer with him and chatting on the balcony of the Pink Elephant bar in Surfers Paradise in early 1994. Dean’s band CHURBRO had been playing that night in the bar, and we were interrupted by a scuffle out on the road between one of his band members and no less than five Englishmen visiting the Gold Coast for holidays. Dean asked me to hold his beer, and dressed immaculately in his stage dress suit, he walked calmly down to the scuffle and lay out the five Englishmen with five punches. He then calmly walked back to the balcony, straightened his suit, and resumed drinking his beer.

It was about the time Once Were Warriors had been released, and I immediately nicknamed him ‘Jake the Muso’. He had an ability to fight, and I am certain he could have pursued a career as a professional boxer. However, despite his raw, full-frontal approach and the hardman leather that saddled him, he is one of the fairest and naturally caring humans I have ever met.

Ironically, surviving to play another day would eventually become the pillars of his temple. He used failure as a platform to discover himself, living through poverty and the process of grunge gigging one day to burying himself in the creation of big-time dance and cabaret show production the next. If the world of music was defined as a currency, then Harawira paid more tax on a non-profit organisation than any other.

He would eventually lose it all and the paint would peel off the walls of his family life, the security of the Island Queen showboat income would be gone, and Dean would have to stare down the image of Father Time being his only paying customer and resurrect himself. To find harmony outside of a vocal pitch in the binds of books, he returned to the most unlikely place on earth for him: he went back to school.

After several years of persistent small successes just paying the bills, Harawira morphed himself into the challenge of returning to school to complete his Bachelor of Music and Diploma in Teaching. As a mature-age student at 40, that decision redefined him, opening passage and new doors to music and equipment, new minds and young souls eager to learn, providing him with a base to use his incredible resource and ear for talent.

Harawira has discovered some of the best artists we have seen in our country for decades, names that are now on household playlists — name such as Ricki Lee-Coulter, Stan Walker, and The Koi Boys, to name a few, have all graduated through the tuition and guidance of Harawira at some point, and to this day they proudly boast about his influence and being the catalyst for their early success.

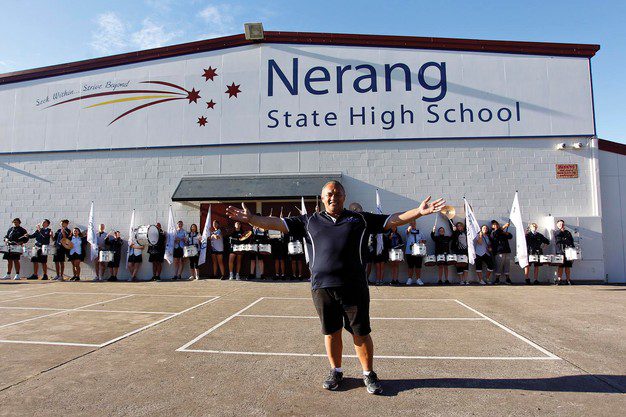

There is not a note known to music that hasn’t passed through the ears of Dean Harawira, as he successfully created the national champion drumline school band at Nerang and has taken the school band to the USA in 2019 for an international tour.

Through all his success as a teacher, being nominated for the ARIA (for the 2018 best music teacher in the land), and from overseeing the successful productions of countless international Polynesian and cabaret shows through Vegas, Europe, Asia, New Zealand, and Australia to continually challenge the boundaries of pragmatic teaching and learning styles, this humble father of four children and five whangai (foster) children has limitless energy and a passion for music like no other.

“Teaching people to play music is only fun if they practise, taking the marriage of chaos and design, the sounds of life, and placing them in a formal place that has been set for it,” he says.

One gets the opinion when talking music to Harawira that he is sufficiently loose about it; there is an undercurrent of clowning and jostling that hides the real process behind the brilliance. As he says, “It is all necessary noise.”

Sitting in rehearsal while he is leading the Nerang State High School band and their internationally famous drumline, I get the picture of why he has this passion and why the group is wildly successful. I get the feeling that his students are engaged in the entire process of learning — objectively and collectively moving through the difficulty of getting the words right and the instruments on the same page, keeping the ritual of this medium from falling apart into the anarchy of separate impulses — and from the simple lifting of a wrist and tap of the conductor’s baton, the wave of a hand, from within all that misplaced clatter punctuated by whatever instrument is now tuned and handy, a piece of beauty is born.

There is a precision and duty in the room, a classical journey back in time, one part played will not work without the other, as the recording creates a nostalgic and hauntingly accessible insight into restoring the moment of this music’s first inscribing. Scattered among the room, there are reminders that this masterpiece was not an accident, with ageing instruments bearing the marks of older students who sat before — their scuffs and bites and dents are the mysterious scars of sound, and in their midst, a soundboard waits to be struck.

To attempt to describe how Harawira creates and conducts this masterful atmosphere feels a little like an invasion of his privacy. Listening to his music is the most inward language that I have known, even transcending my thought. It is a captivating image, watching him stand at the front, head slightly tilted toward the band, with a mindful and watchful ear.

Sitting and listening, the room vibrating, I feel like the intruder in the room. I am captivated, afraid to move for fear of unsettling the sound waves. The entire emotion is a symphony of players in command.

Their precision generates hope of a younger generation and leaves me with the thought that whatever life holds at home or in school for these students, whatever might be lost or broken or forgotten in the world, is really nothing at all to be concerned about, because this group has a sense of belonging and dedication to this room, through this simple blessing in unison, the migration of sound, one eye on the page, one eye on the hand, contemplating Dean Harawira nodding his head in rhythm with the tune.

Ricki-Lee Coulter

“Wow, Dean is an amazing teacher. He gave me my first break and pushed me and pushed me. He made me stand out the front when I had no confidence, he made me talk to the crowd and made me sing. I owe him so much; he taught me how to perform and work with a crowd.”

The Koi Boys

“Shout-out to Dean Harawira — wonderful teacher and a dear friend, has done a great job with the kids; he has taught us a lot and helped us all when we were starting out.”

Stan Walker

“He deserves everything — he got me into music, taught me everything I know; the best music teacher.”