PEOPLE

The PHIL AVALON Story

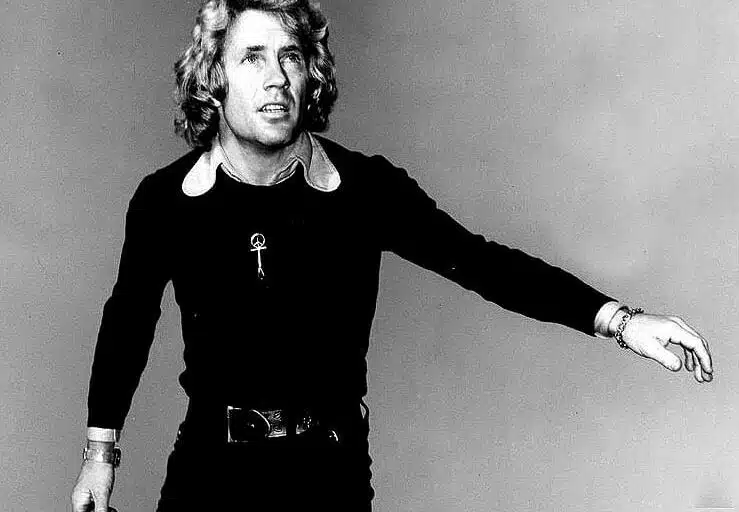

WORDS: Greg Pride PHOTOGRAPHY Supplied

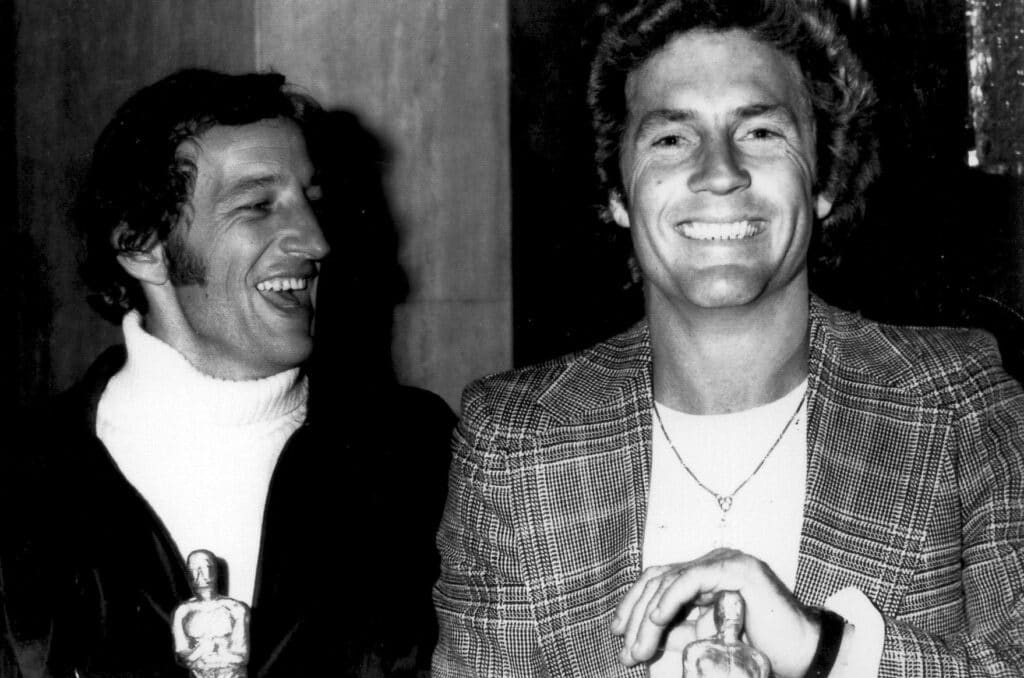

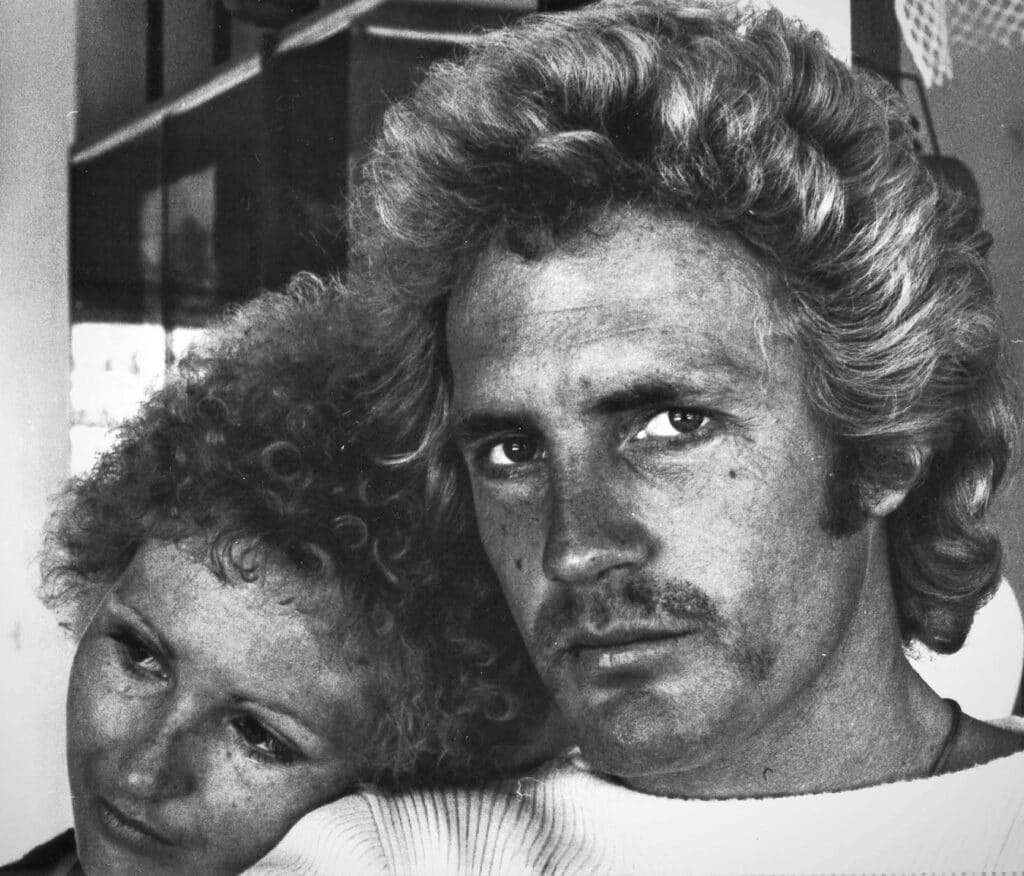

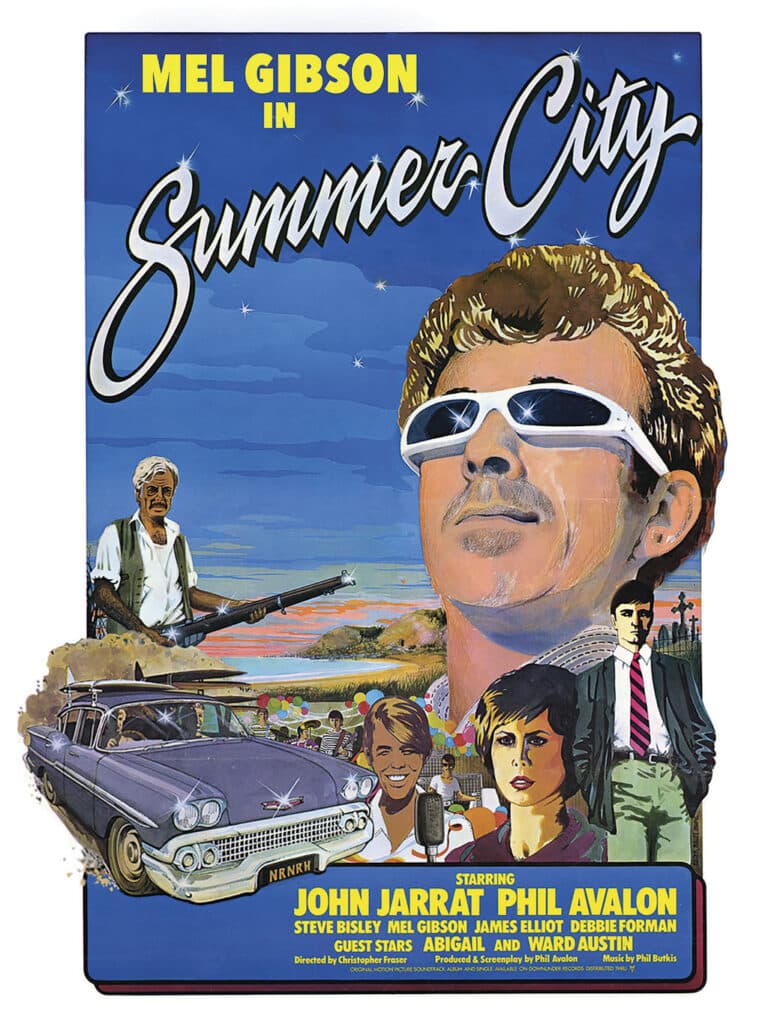

IN 1977, when young film-maker Phil Avalon was casting for actors for his upcoming surfing thriller Summer City, three fellow drama school students came into the frame. Their names were Mel Gibson, John Jarratt and Steve Bisley and the rest, as they say, is history.

Summer City was not just a very successful movie that became a cult classic; it also proved to be a launching pad for the trio (alongside Avalon), who have since gone on to screen stardom (in Gibson’s case, mega-stardom).

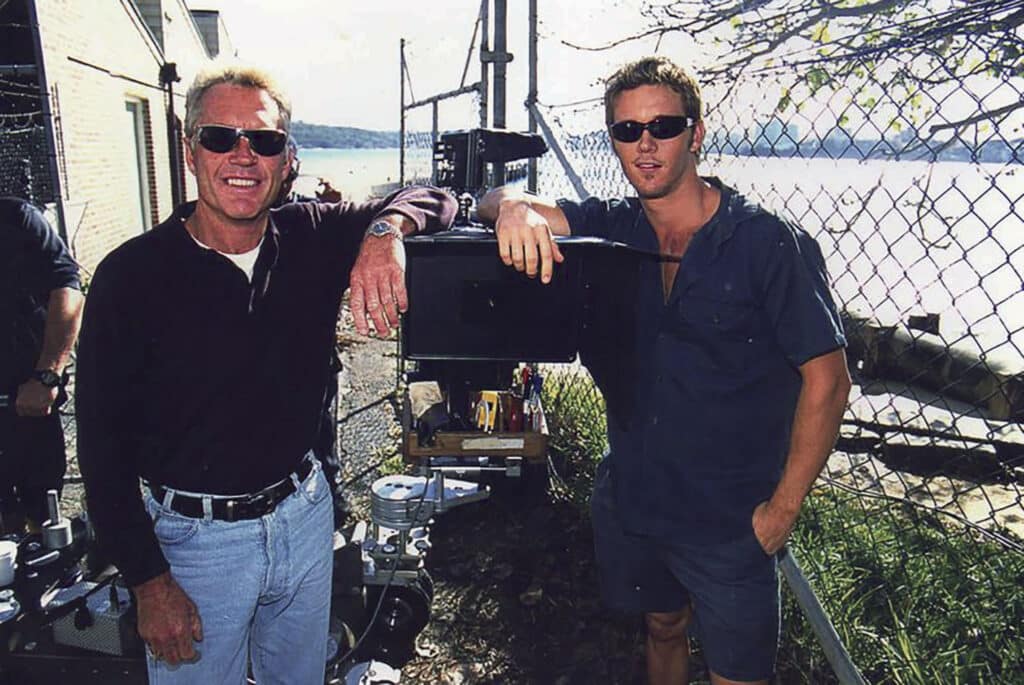

Avalon is about to release Sons of Summer, the second sequel to Summer City, and anticipation is running high for the movie which features Kiwi actor Temuera Morrison – of Once Were Warriors and Boba Fett fame – Aussie screen darling Isabel Lucas and Gold Coast-based rising star Joe Davidson.

The film was shot entirely on the Gold Coast, where Avalon – one of the legends and great characters of the Australian film industry – has been based for the past 20 years.

Ocean Road caught up with him recently at the Main Beach apartment he shares with partner Olga and dog Bo, “the pomeranian who thinks he’s a lion”. Across the road is the beach where Avalon, a self-confessed “grey grommet”, surfs daily between working on his latest film or stage project.

We start by asking him about his early life, growing up in Newcastle, and how he found himself in the film industry.

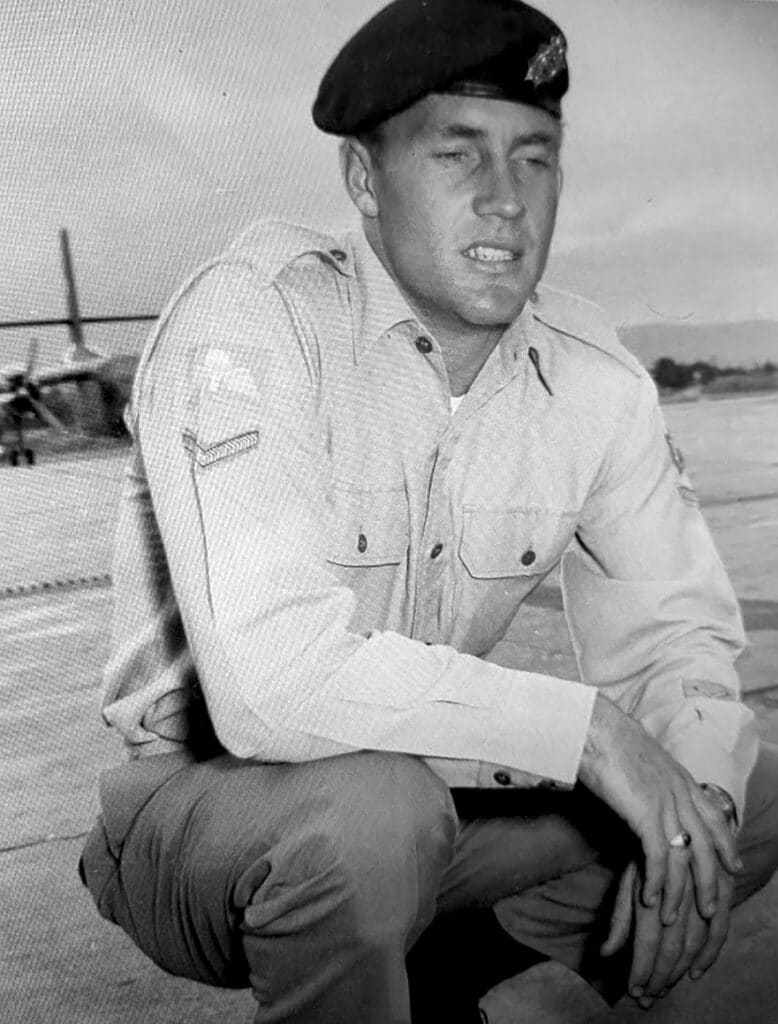

“I was in the army at 16 – mum got me enlisted, she thought I needed waking up,” Avalon says with a laugh over coffee and biscuits on his balcony.

“Mum was a music teacher and dad was a singer in a big band, so I always loved the arts. It was a bit weird in those years in Newcastle, a steel town, having an artistic bent rather than being a coal miner or whatever, but that was me.”

Avalon, then known as Phillip Holbrow (more about that later), was also a keen and talented surfer who competed successfully. Professional surfing, however, was still a way off.

“There wasn’t anything like today’s professional surfing back then, so it would have been a lean and mean career choice,” he says.

During his six years in the army, Avalon met many fellow soldiers who had never even been to the cinema, let alone seen a stage show.

“They’d never been exposed to the arts so on a Tuesday afternoon, when we were supposed to be at footy practice, I’d take them to the movies or to see a stage play or whatever,” he says.

“I could see the effect that it had on them. Instead of going to footy training, we were going to see Paul Newman or Steve McQueen in a movie, and the guys loved it.”

Avalon was in the army during the Vietnam War era but managed to avoid the long-running and controversial conflict.

“I was a crew commander in an army aircraft and they gave us a choice to go to New Guinea or Vietnam,” he says.

“I asked them ‘which one pays the highest?’ and they said ‘New Guinea’ so that’s where I ended up. I was in New Guinea for a while and played in a little band up there.”

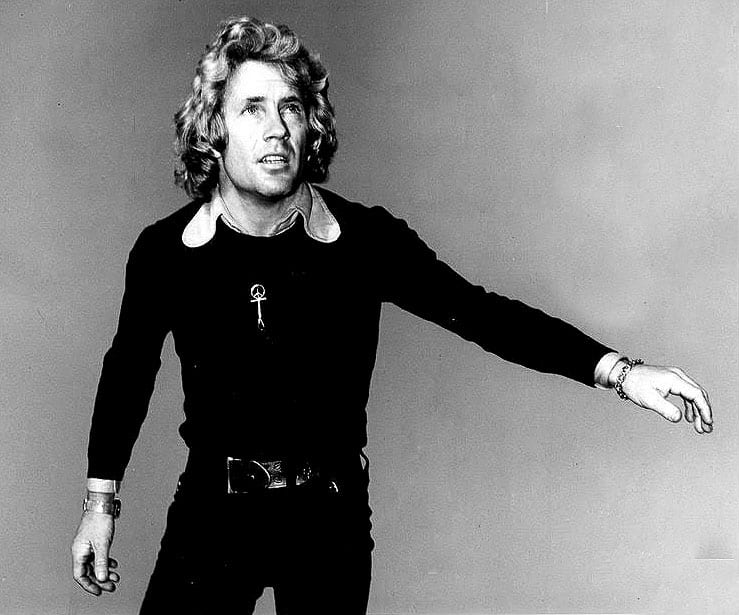

After finishing his military service, Avalon enrolled in drama school while also working as a model. While still studying, he wrote, produced and starred in Australia’s first telemovie, Double Dealer, which he self-financed through modelling gigs.

“Unfortunately, I never got to finish it because the sound on it needed fixing and I just didn’t have the money,” he says.

Then came Summer City, which he funded with the help of mates “and cast a guy named Mel Gibson”.

John Jarratt, a National Institute of Dramatic Art graduate who had starred in the acclaimed 1975 film Picnic at Hanging Rock, had come on board for Summer City and recommended NIDA students Gibson and Bisley for roles.

“I tested them, they got the roles and we made Summer City,” Avalon says.

“It did very well – it was one of the first films to capture the Australian youth surfing culture in a genuine way.”

The plot centres on four young surfers – Scollop (Gibson), Sandy (Jarratt), Boo (Bisley) and Robbie (Avalon) – who leave Sydney for a bachelor party/surfing weekend before Sandy’s impending wedding, only for one of them to be murdered.

The movie was shot mainly around Catherine Hill Bay, south of Newcastle, and in his 2015 memoir From Steel City to Hollywood, Avalon recalls one hilarious incident during filming.

Made on a shoestring budget so tight he was “running out of laces”, Avalon had hired the tiny Catherine Hill Bay RSL Hall for $100 a week to use for filming and double as accommodation for cast and crew. All good, except they had to share the venue one Saturday night with a wedding.

“The cast and crew headed off to the pub,’’ Avalon wrote in his book.

“I had arranged to meet (then-wife) Karmen for dinner in Swansea. The cast and crew agreed to meet back at the hall at midnight when the wedding party had finished their celebrations so we could clean the hall, get the mattresses back out and get to bed.

“We were shooting a surfing sequence the next day and I wanted to capture the sunrise, so it was a 5 am call.”

Gibson and Bisley, who would team up again two years later for the landmark film Mad Max, headed to the pub for a skinful of schooners.

When they wandered back to the hall, the wedding was still in full swing, so they decided to hurry things along by “mooning” guests through the window.

With the reception erupting in howls of outrage and menfolk rushing for the door to deal with whoever had pointed their rear ends at the bride and groom, Gibson and Bisley bolted into the night.

Returning with Karmen to find themselves surrounded by a group baying for blood, Avalon seized an old .303 rifle from the back seat.

The gun was a prop for the film but the sight of it being shoved out the window of his car forced the crowd back a few steps.

“We thought you were one of the guys that put shit on our wedding,’’ one said. “You’re from the movie mob, right?’’

“Yes,’’ Avalon replied. “I’m the producer. What happened?’’

“Two of the movie guys showed their bare bums at the hall window,’’ the man said.

“Are you sure it was guys from the movie?’’ Avalon asked.

“Yep, Joe here recognised one of them.’’ Avalon struggled to keep a straight face, thinking to himself: “He recognised one of their bare bums?!’’

Summer City opened in Sydney at the old Century Cinema around the same time as the original Star Wars.

Within a week, screenings at the 1800-seat theatre were selling out, helped by publicity including a “terrific review” by ABC film reviewer John Hinde which lured then-Prime Minister Gough Whitlam and wife Margaret to the theatre to see the film.

Avalon saw the Whitlams in the queue and spoke to them.

“I said to him ‘What made you come here’ and he said, ‘I love Australian movies and talent, and John Hinde gave you five stars’.’’

Avalon took the movie on the road, including a brief season at the old Burleigh drive-in.

“Summer City did very well at the box office and internationally as well,” he says.

“It’s one of those films that’s timeless and I’m very proud of it. It still plays in surf museums and reminiscent events. People like Tarantino and Elliott Gould have given it a nod, so we got it right.

“It was the beginning of the renaissance of the Australian film industry, so I was very fortunate as a young guy to be there.

“I thought at the time when I was working with Gibson ‘gee, he’s got a great presence, good voice’ and I reported that to the casting director for the movie Tim (based on the 1974 novel by The Thorn Birds author Colleen McCullough).

“Mel got the gig and won an AFI award and then of course went on to do Mad Max.

“He became one of the biggest stars in the world. Jarratt’s done very well too, as has Bisley. Everyone’s done exceptionally well so I’m happy. And I’ve helped others since that time as well.”

They include True Blood star Ryan Kwanten, who appeared in Liquid Bridge, another surfing drama that Avalon made in 2003.

He very nearly also helped launch Russell Crowe’s career when he auditioned him for the 1991 film Fatal Bond, starring The Exorcist’s Linda Blair, only for the studio to intervene and request he cast Gibson’s brother Donal instead.

“I look back at my earlier films with a smile,” Avalon says.

“This is a transient business – it’s that caravan, that group on this show and you may never see them again. Or you may be lucky enough to be able to work with them again or stay in contact.

“It can also be a lonely business, especially when you’re a writer as well as a producer. I actually enjoy writing the most. I’ve written probably 30 to 40 films, half of which have been made.

“If you get a film that’s successful you get offers to do others. I had a lot of offers straight after Summer City, and I ended up doing a film called Little Boy Lost.”

The 1978 film, which also starred Jarratt, was based on the true story of Steven Walls, a four-year-old who went missing in the Australian bush for four days in February 1960.

His disappearance sparked one of the nation’s biggest-ever searches, became a legend in Australian folklore and spawned a hit song called Little Boy Lost.

Avalon’s filmography also includes Breaking Loose, a 1988 sequel to Summer City starring Peter Phelps and TV screen siren Abigail, which also did “very well”.

Avalon also had his own film studios in Sydney where the smash hit Crocodile Dundee was filmed, as well as the 1989 adventure/drama Trouble in Paradise starring Raquel Welch and Aussie screen legend Jack Thompson.

“That film was financed by Christopher Skase,” Avalon recalls with a wry smile.

“I was the last one to get paid, but I did get paid.”

Speaking of Thompson, Avalon has a story about him too.

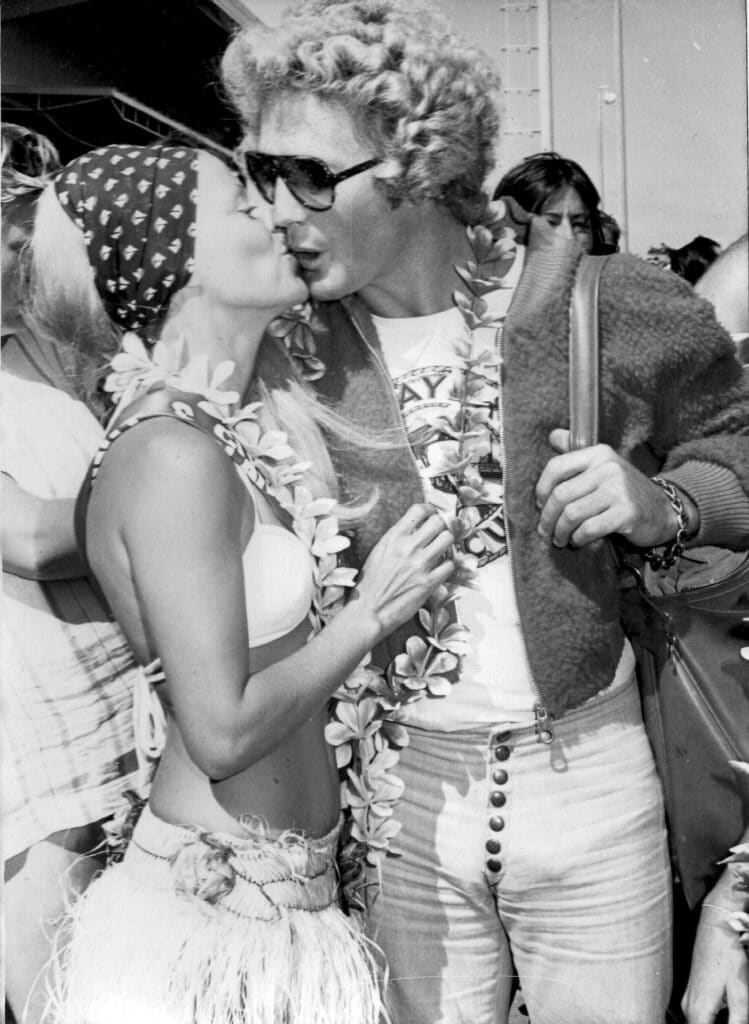

As mentioned earlier, Avalon was a top male model in his early years and used the proceeds to help fund his film career.

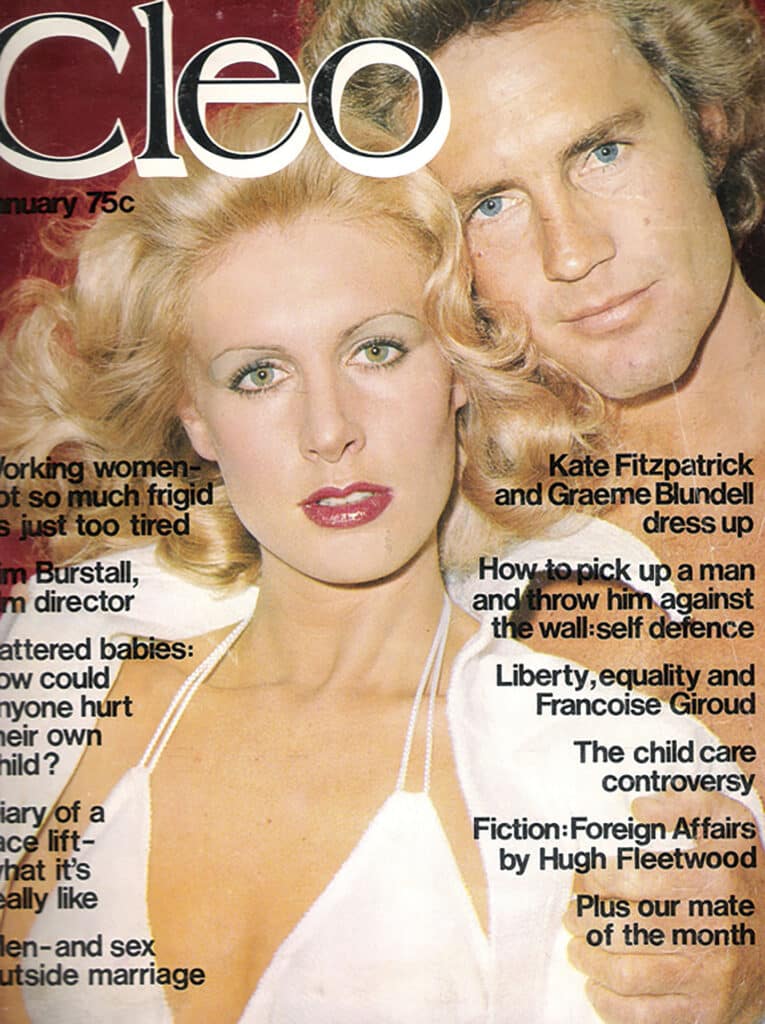

In 1972, Ita Buttrose – editor of the Kerry Packer-owned women’s magazine Cleo – came knocking with an offer to become the publication’s first male centrefold. His agent told him the gig would pay handsomely but when he was offered just $400, he knocked it back.

Thompson, then one of Australia’s top actors, agreed to get his gear off for a lark and the same fee.

Avalon, however, trumped Thompson soon after when he became Cleo’s first-ever cover guy, with a spread that included him butt naked astride a motorcycle. It led to a much-more lucrative photo shoot for US magazine Playgirl, which he agreed to do only after being told the magazine would not be seen in Australia by his schoolteacher mum Hazel.

“It was a massive fee, I got a trip to America and had a wonderful year on the back of that one,” he chuckles.

Avalon still has lunch weekly with the man who gave him his nom de plume, famed former radio disc jockey Graham ‘Spider’ Webb.

Webb, whose career included working extensively on the UK’s famous pirate radio ships that inspired the 2009 film The Boat That Rocked, was involved in a TV show called Blind Date and Avalon was invited on.

“Graham said to me, ‘you can’t use Phillip Holbrow, let’s come up with another name’,” Avalon recalls.

“I said, ‘I like Avalon because I surf at (Sydney’s) Avalon beach’. He said, ‘OK you’re Phillip Avalon’. I used Graham as an extra on a couple of my movies as a payback. He lives on the Coast and he and I catch up for lunch every week.”

Avalon says Sons of Summer came about pre-Covid when a US film financier flew out to ask him and co-writer Greg Clayton to do a remake, as streaming services were hungry for content.

“He’s an old Brissie boy and Summer City was one of the favourite films of his youth,” he says.

“I told him I was interested but would like to update it, not remake it. He agreed and flew out here three or four times. Then Covid hit and really smacked us.”

When the pandemic eased, the investor told Avalon that he was no longer in a position to back the film, but the producer managed to assemble a new group of financiers.

“The international distributor said he had faith in the project and if we decided to proceed, he’d also support it,” he says.

“We shot it over six weeks last June and it rained the whole time, but you wouldn’t know it on the film. We got just enough glimpses of sunshine to make it work.”

Avalon says Morrison agreed to get involved after reading the script, in which he was cast in a different role to the one he plays in the film.

“Temuera came back and said ‘I like the script but I’d prefer to play the bad guy’,” Avalon says.

“I said ‘really, I think we’ve already cast that’. So I went back to the actor who had been cast as the bad guy and asked him if he’d mind swapping. He said ‘you’re joking, Temuera’s one of the greatest actors on the planet, of course I’ll step down and play that other role’.

“Temuera’s a great human being, a wonderful actor and a beautiful man offscreen. Nothing was too hard and there were no demands, even though at the time he was this massive star as Boba Fett.

“It’s the first time I’ve worked with him and he’s an actor I’d love to work with again.”

He is hopeful the new film will be as big a success as Summer City.

“We already know that there’s big interest in it internationally, which is a blessing,” he says.

“So that gives us a little bit of comfort, but you just never know. I’ve seen films where I’ve gone ‘wow, this is going to kill it at the box office’ and it runs a week and it’s gone. With others that have been successful, I’ve gone ‘how the hell did that happen?’

“The trick in film-making is you’ve got five minutes to attract an audience. If you don’t get them there and then – especially nowadays when they’ve got a remote control in their hands – you lose them. I learned that very early on in my career.”

Asked for his take on the Gold Coast film industry, Avalon says he’d like to see more support from Screen Queensland for grassroots independent productions as opposed to the big-budget international films.

“The Gold Coast City Council really goes out of their way to help us – they’re No.1 in my book,” he says.

“Screen Queensland, they’re encouraging overseas productions to be shot here, whereas I think they should focus more on domestic product, I really do. I don’t think they’re supporting domestic product enough.

“For us independent film-makers, they’re a no-go, and that’s a great shame because we’re making Australian stories. And that should be encouraged.”

Avalon admits he’s “in the sunset” of his career but still has a few more projects in him, in between riding the waves.

“I get a lot of offers to do stuff and I’m pretty particular about what I do,” he says.

“I’m still enjoying it and I’ve still got the passion.”

Avalon was having coffee with some friends recently when Summer City, a song he recorded at the same time as the movie, came on the radio.

“Someone said ‘have you ever thought how many young guys would have loved to have had a hit record, produce and star in a movie and own a movie studio?’”,” he says

“I’d never really thought about it before but when I reflect on it, I guess it was definitely a case of ‘right place, right time’.”