BUSINESS

Hyper-Truth

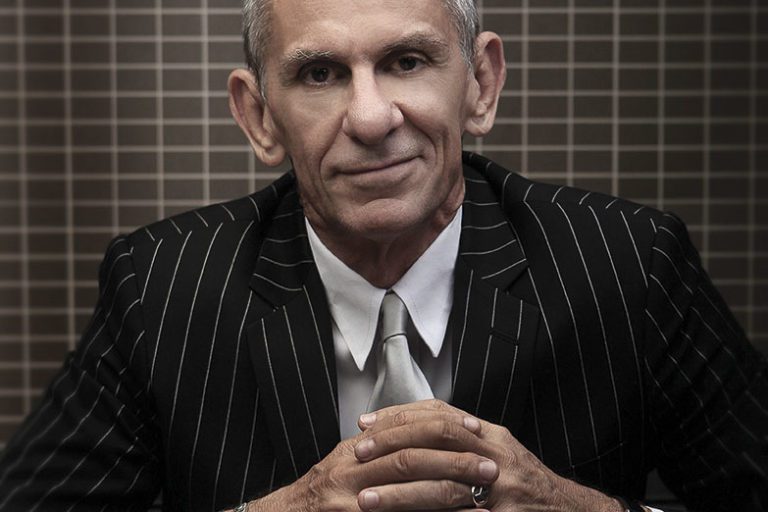

WORDS: Chris Nyst PHOTOGRAPHY Supplied

The internet has made it increasingly difficult to discern where truth ends and fantasy begins.

MORE than 40 years ago, the postmodernist French philosopher Jean Baudrillard observed that: “We live in a world where there is more and more information and less and less meaning.” The celebrated social theorist warned the Western world was teetering precariously on the edge of a crisis of information overload, in which simulacra – recycled images, ideas and symbols – would begin to take precedence over reality itself.

The term simulacrum was first reported in the English language in the late 16th century, describing a representation, such as a statue or painting, often an inferior substitute for the original it purports to portray. Simulacra, and the so-often-vexed process of image-creation, have intrigued the philosophical mind for millennia.

As long ago as the fourth century BC, the philosopher Plato, in his dialogue Sophist, cited the Greek art of sculpture as a metaphorical example of the human tendency to distort truth to reflect the viewpoint of its beholder. In those ancient times, statues of kings, warriors and gods were carved so that the image was larger at the top than it was at the bottom, such that viewers peering up at it from the ground saw it in perfect proportion. Thus, Plato argued, so-called truth and history were often similarly misshapen.

In his 1981 treatise Simulacra and Simulation, Jean Baudrillard concluded that sometimes a simulacrum becomes not just a copy of the real, but a new version of reality itself, one he described as ‘the hyperreal’ – a truth in its own right, which wholly supplants the original. The ever more pervasive dumbing-down of information by contemporary media, Baudrillard argued, was driving an unstoppable collapse of meaning, making it increasingly difficult to discern where truth ended and fantasy began.

While Simulacra and Simulation was published well before the internet revolution, Baudrillard’s words may be truer today than they ever were.

Consider the curious case of Caleb Cain. As a disillusioned, young, white American male growing up in the late 2000s, Caleb became fascinated by internet culture. He and his friends spent hours playing online games and then graduated to watching videos of intellectuals debating life’s big issues. Raised in a conservative Christian family, Caleb was a liberal who cared about social values. But he was also young and unsettled and when he eventually dropped out of college, he was a little bit lost and looking for answers. So he searched for them in the place where he spent most of his time – online – and he eventually found them on the video-sharing and social media platform YouTube.

In late 2014, YouTube recommended a self-help video by Canadian talk show host Stefan Molyneux. A passionate, self-styled philosopher, Molyneux offered the impressionable young Caleb everyday tips on how to negotiate life’s many hurdles and benefit from self-improvement. But Molyneux was also an avowed ‘anarcho-capitalist’, a far-right commentator who aggressively opposed feminism and race and gender politics. He was smart, outspoken and funny and he addressed young men’s issues directly, in a way Caleb had never heard before.

Before long, Caleb dived headlong into the YouTube universe, watching dozens of clips by right-wing conspiracy theorists who sold their messages of anti-feminism and white nationalism with an entertaining mix of sarcasm, satire and comedy. They packaged it all in a wrapper of irreverent free speech, casting themselves as straight-talking rebels pushing back against the humourless feminists and ‘social justice warriors’ who had hi-jacked mainstream social dialogue.

Caleb was convinced YouTube had introduced him into a cool, exclusive club – the enlightened few who knew the hyper-truth.

What he didn’t know was that YouTube had locked him, and others like him, in a self-affirming house of mirrors. Two years earlier, the platform’s engineers had made an update to its recommendations algorithm. Previously, the algorithm had been programmed to maximise the number of videos a viewer clicked on, but the YouTube executives now decided the algorithm should target watch-time, rather than views. Instead of going from one view to another, the new recommendation algorithm ensured viewers stayed longer on their chosen site and then moved on to a new video that complimented and reinforced the message of the first.

For the next three years, the platform’s watch time grew by 50 per cent a year, while the number of views shrank as viewers enjoyed a video-fest of more-and-more of what they already knew, loved and believed – and completely side-stepped all opposing views and debate. YouTube’s resultant exponential growth was driven overwhelmingly by right-wing populism and Caleb Cain found himself swept along with it.

Donald Trump’s unexpected election to the US Presidency in November 2016 felt like a ringing vindication and Caleb’s online consumption suddenly went through the roof. He listened to his favourite YouTube creators for up to 17 hours a day and watched nearly 4000 YouTube videos in the following 12 months.

In this modern era of the internet, like Caleb Cain, most people take much of their information and their inspiration from the web. In the process, sometimes they are misled, sometimes mistaken and sometimes just plain deluded. In March 2019, a white nationalist gunman who live-streamed video of himself murdering Muslim worshippers in two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, signed off with the words: “Remember lads, subscribe to PewDiePie.” It was a reference to a 29-year-old Swedish content creator whose YouTube channel has more than 111 million subscribers and 28.1 billion views to date. PewDiePie is currently rated by Time magazine as one of the world’s most influential people.

At a time when COVID has made online contact more ubiquitous than ever, we are increasingly susceptible to algorithmic constructs that channel to us versions of the Truth peddled by a disparate myriad of untested sources. Now, more than ever, we must remember they include the irresponsible, the ill-informed and the intentionally dishonest.