ENVIRONMENT

Who says our CHANGE ACTIVISTS have to be Adults?

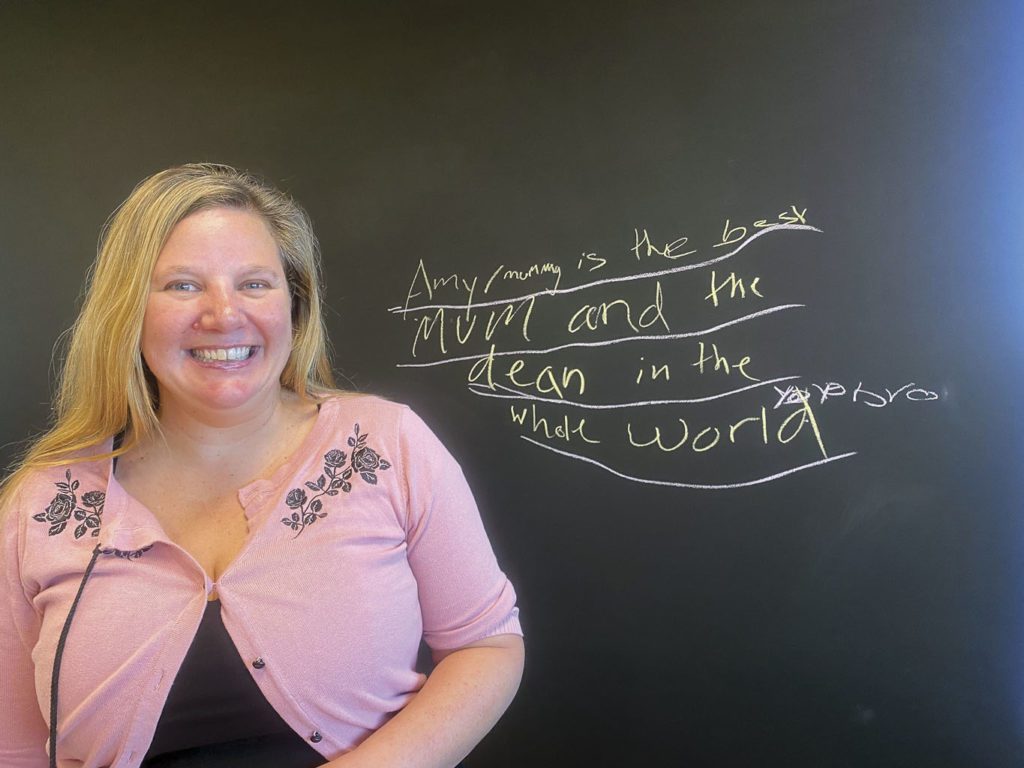

WORDS: Yasmin Nelson PHOTOGRAPHY Supplied - Southern Cross University

A new initiative at Southern Cross University is taking children and young people on a climate action-adventure to inform and educate them about the challenges facing different parts of planet Earth.

LIVING at Tamborine Mountain, or as she likes to call it, ‘The Spider Hotel’, Professor Amy Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles knows how powerful a connection with nature can be, especially in the early years of a child’s life.

The Executive Dean of Education at Southern Cross University and mother-of-two has led more than 40 research projects in environmental education resulting in more than 150 publications, with children and young people’s voices at the forefront of her research. Whether it be climate change, nature play, or diversifying the traditional teaching curriculum, Amy makes sure children and young people have a chance to be heard.

The ecological philosopher grew up in Tieri, a small town in Central Queensland, where her father worked in the mines. Amy admits her upbringing in a coal-mining town is ironic given her advocacy for environmental change.

“He (Dad) always used to talk about how he was bothered by open-cut mining and how they don’t leave a tree. Eventually, he became part of the union for central Queensland and was involved in the environmental regeneration plans. His journey from being pro-mining to then questioning it rubbed off on me too,” Amy says.

Amy has led the Faculty of Education at Southern Cross University for the past three years. Paradoxically, she was a self-described ‘disengaged’ student throughout primary school, in the small, landlocked town more than 500km from any ocean.

“I was mostly bored. Sometimes I would leave school and go home at lunchtime or go out into the bush. That was the really exciting thing about being in a country town school – just having access to nature,” she says.

Fast-forward to Year 7, where it took just one teacher to shift Amy’s engagement in learning. She calls him Mr F.

“He was a very worldly character and really honoured children and I respected that so deeply. I went from being an average student to a straight-A student and then it never really stopped. Something switched on and I became very passionate about learning,” Amy says.

“Then I had other teachers in Years 11 and 12 who were equally as inspiring in that way. They opened up topics for me like climate change and had me reading Thoreau, an 18th Century environmental philosopher.”

Amy’s passion for science, geography and the environment stuck well into her 30s and propelled her into an impressive academic career. As well as heading up the Faculty of Education, she also now leads the ‘Sustainability, Environment and the Arts in Education’ (SEAE) research cluster at Southern Cross University. The team focuses on climate change education, nature play, the Anthropocene and posthuman philosophy.

Their latest endeavour is ‘The Climate Action Adventure!’ web application. The collaborative project, with 20 children and young people, has been designed as an adventure game to inform and educate them about the challenges facing different parts of planet Earth.

After registering, players join avatars Aoi and Elbereth on a climate action-adventure and choose from four different ‘scapes’ currently being impacted by climate change: Desertscapes, Forestscapes, Arcticscapes and Cityscapes. As they explore each of these environments, players encounter ‘climate concerns’ that have been sourced from children, young people and adults through extended social media networks.

The safe space offers a range of peer-reviewed resources about climate change and a series of actions designed by young people to allow everyone to engage with sustainable, responsible practices.

“This game app is not only exciting but is inspiring too. It enables children and young people to contribute meaningfully to climate change conversations,” Amy says.

Kiki Gonzales, a Year 7 student from Kingscliff High School, co-designed the app and found the experience inspiring.

“I found contributing to creating an environmental app was a great way to raise awareness for young people on this critical issue,” Kiki says. “Being part of this experience also helped improve my collaboration skills, and for this, I would like to say a big thanks to all the amazing mentors and peers on the project.”

The most influential and thought-provoking conversations about our global climate crisis have recently come from those people born in the past 20 years.

“They’re going to get louder and louder and more power to them,” Amy says.

“Ten years ago, I didn’t think it was conceivable that millions of children and people would be striking from schools. Children have a better understanding that climate change is as much a relational and cultural issue as it is a scientific issue. Some children have said things like ‘humans don’t even know they’re animals anymore’.

“In the deep history of time, we’ve been here for a blip compared to the time that the Earth’s been here and kids really get that.”

It’s no coincidence TIME’s 2019 Person of the Year was Greta Thunberg, a 19-year-old Swedish environmental activist known for her youthful and straightforward manner.

“People like Greta Thunberg don’t need to be given a platform. She created it herself. I see more and more of that – where kids aren’t waiting for adults,” Amy says.

“There are limited politicians who are standing there too and that’s where there’s a deep frustration. However, we’ve seen great change with or without politicians. When you look at some of the greatest achievements of humanity, that hasn’t always happened because of government – it’s happened in spite of government.”

It’s no surprise that Amy was one of the youngest women in Australia to become a full professor at just 37. Rather than simply accepting the way things are, Amy has built a career looking outside the box. A recent example is building Indigenous philosophies and practices into teacher education.

“We’ve now incorporated this type of research into our curriculum at Southern Cross University, where from 2022, our Bachelor of Education and Master of Teaching now include a unit each on environmental education and Indigenous education, as foundation subjects rather than electives,” she says.

When Amy is asked what an ideal teaching curriculum would look like, she says it’s up to the children to decide.

“I’d want children and young people involved in taking ownership of what they think their education should be. If you were to ask an Indigenous student how they think schools should look, I don’t think it would be as it is right now. Diversity of different schooling systems is an excellent thing, but this drive to be chasing a one-size-fits-all curriculum is the antithesis to that,” she says.

“For instance, Arcadia College on the Gold Coast is specifically designed for young people who are disengaged from mainstream schooling. That doesn’t mean these kids aren’t highly intelligent – most of them are. But the school employs alternative, arts-based learning to engage them. That’s a good example of how school can be done differently and work really well for those young people.”

Recently, Amy has been working on the new ‘Mudbook Framework,’ a project co-designed with early childhood educators and children who participated in a Horizon project funded by the Queensland Government, researching the rapid resurgence in supporting open, free nature play in education settings.

“We were seeing a lot of publications claiming that children spend significantly less time in nature. And now we are seeing more and more programs deliberately focused on nature play and Bush kindy and forest schools, with the intent of building up those connections with nature – so our research is specifically about how young children aged four to five years old learn scientific concepts through nature play,” Amy says.

The research was a joint project between Southern Cross University, RMIT and Swinburne, with partners including Nature Play QLD and QLD Early Childhood Teachers’ Association.

“The Mudbook is an entry point not only for other educators to expand their practice but also for parents and families as well to understand how nature play builds environmentally-led STEM learning. The project revealed nine types of nature play with the most common science concepts being earth, weathering, relations, materials, bodies, time and ecologies.”

The pedagogical nature play framework (the Mudbook) used cartography to map children’s and educators’ existing nature play conceptions and involved 20 early childhood education settings across Queensland.

The research team found that numerous early childhood education settings also placed a focus on Indigenous heritage.

“They would apply pedagogies like Country-responsive play, where it wasn’t only about doing an Acknowledgement of Country at the beginning of the day or session, but where the Acknowledgement was absolutely embodied in the practice itself.”

One of Amy’s next research projects is called ‘climate country’ and involves working with Indigenous and non-Indigenous young people on climate change.

Away from work, you can find Amy either swimming or outside in her sustainable garden, with plenty of dogs, cats, guinea pigs, and of course her husband and two children, Lily (13) and Finley (9).

You can keep up to date with Amy’s work at www.climatechangeandme.com.au or https://childhoodnatureplay.com