GREAT OUTDOORS

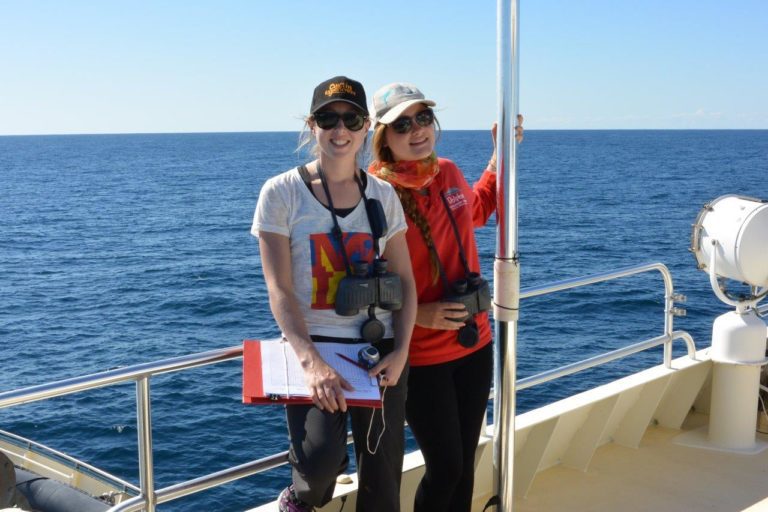

When a tape measure won’t do – measuring whales

WORDS: PHOTOGRAPHY

Anyone who’s ever tried to measure a whale will know how difficult that is. Assessing their size and body condition is a rather large problem.

For Southern Cross University PhD candidate and scientist Grace Russell, the solution is to use unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), or drones, to photograph the whales from above; before taking measurements from the photographs.

“I’ll use photogrammetry techniques to get morphometric (size and shape) measurements and individual body condition,” she explains.

Ms Russell will use this data to compare the whales’ body condition within different reproductive classes such as juveniles, adults, pregnant whales, lactating whales and calves; and make comparisons between their northward and southbound migrations.

“I am also aiming to compare the west and east coast populations of humpback whales, and how this may differ between the two putative (considered to be) distinct breeding populations.”

One may well ask why?

“In the face of a changing environment and increasing human activity, it’s vital to understand how species respond to stressors in their environment, so that we are able to help mitigate the negative impacts on population recovery, health and growth,” said Ms Russell.

Assessing a whale’s body condition is one way to monitor individual and population level health.

“Body condition is a reflection of a whale’s foraging success in the feeding grounds and it will have an impact on the amount of time they are able to spend in their breeding grounds reproducing, competing for breeding opportunities, or calving. This will also influence how much energy a mother will be able to pass onto her calves; this energy is vital for calf growth and survival,” said Ms Russell.

Humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) are capital breeders relying on endogenous (originating from within) energy to sustain reproduction and migration during a period of fasting.

During this time individual whales expend large amounts of energy for one of the most important life stages; breeding and calving. Body condition is a key descriptor of individual energy stores and can serve as a link to ecological fitness.

“Improving our understanding of body condition in free-living whales can lead to improved knowledge on reproductive capacity, population health and viability, and understanding responses to environmental and anthropogenic changes. Despite its importance, little information is available on the relationship between humpback migration and body condition.”

The segregation of humpback whale migration timing is well documented, however the factors that contribute to this timing is unclear.

“Increasing our understanding of migration patterns in relation to body condition may help us predict future consequences of climate change, and how this may impact their migration or their reproductive success. For example, individuals with reduced fat reserves – maybe due to decreased prey availability in their feeding grounds, or stressors in their environment – may have a decreased chance of reproducing successfully.”

“In addition, calf survival may be compromised due to their mothers reduced energy reserves, or females may skip a reproductive cycle in order to ensure they have enough energy reserves for future pregnancy. Males may also spend less time on the breeding grounds if they do not have sufficient energy reserves, decreasing their breeding opportunities.”

This study will use UAVs to gain vertical images of humpback and blue whales in Australian waters.

“I’m hypothesising that there will be a different relationship between body condition and migration timing between the west and east coast populations. This is because there are significant feeding opportunities where humpbacks have been observed feeding in Eden, Tasmania and New Zealand. What these feeding opportunities mean for body condition and migration timing we are not too sure, but it will be interesting to see the results.”

Ms Russell has successfully obtained funding for her research from the Holsworth Wildlife Research Endowment/Ecological Society of Australia.

The first phase of research on the West Coast has been delayed due to Covid-19 but the current plan is to start the field season on the East Coast in early June.

“It’s such a challenge to study marine mammals, especially the ones that don’t come to the surface that often. I find I am rewarded more with the more effort I put in. The allusive nature of some marine species, the distances they travel and their surface time all present challenges to try and study these species, and I think the more you challenge yourself, the more rewarding it is when you succeed.”

Ms Russell has previously studied heat dissipation behaviours in Australian desert birds, done an internship in China with Giant Pandas, volunteered in Africa with the Born Free Foundation, and processed data for an NGO in the Congo on Western low land Gorillas.