PEOPLE

Vietnam: My Story of Service – and Recovery

WORDS: PHOTOGRAPHY

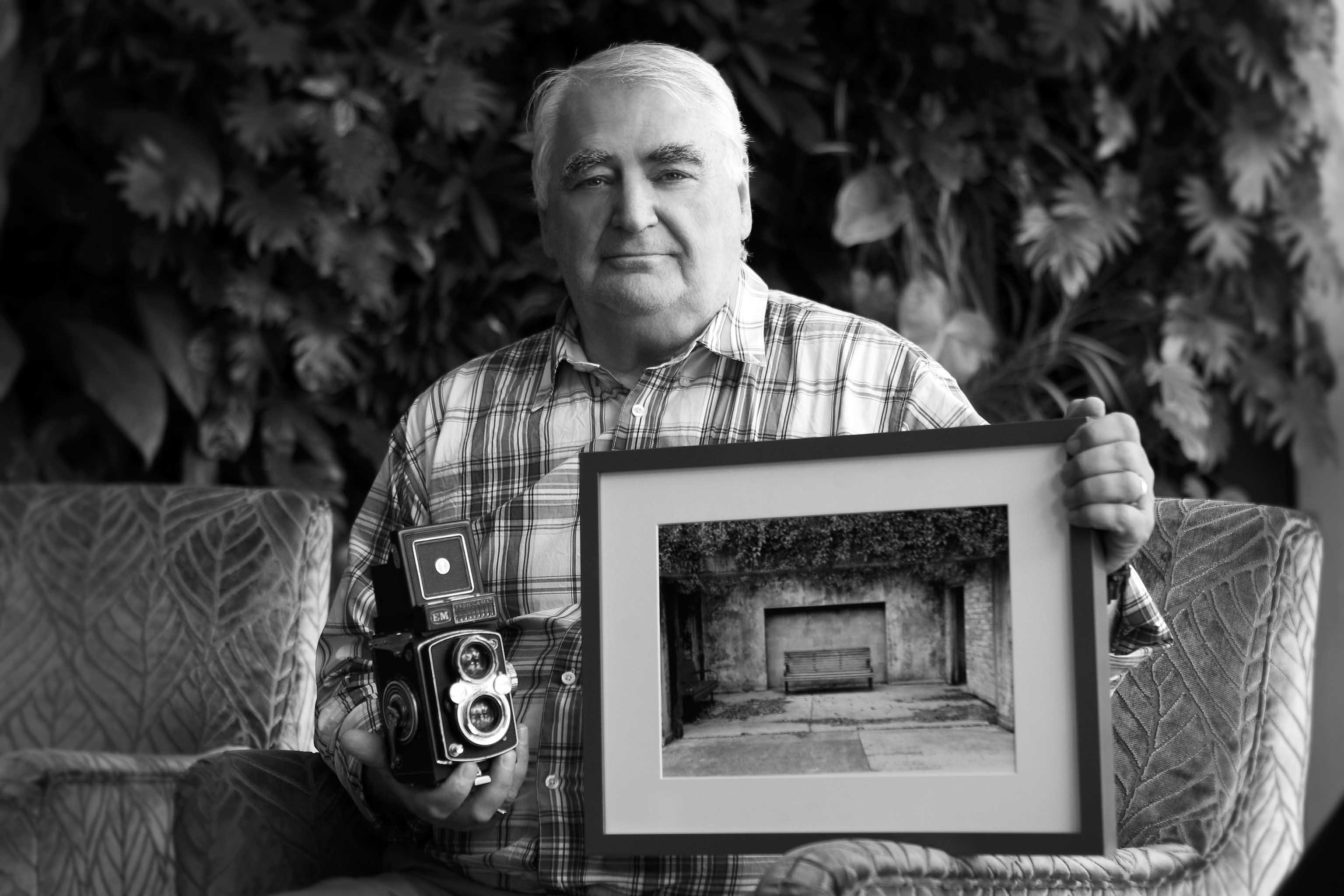

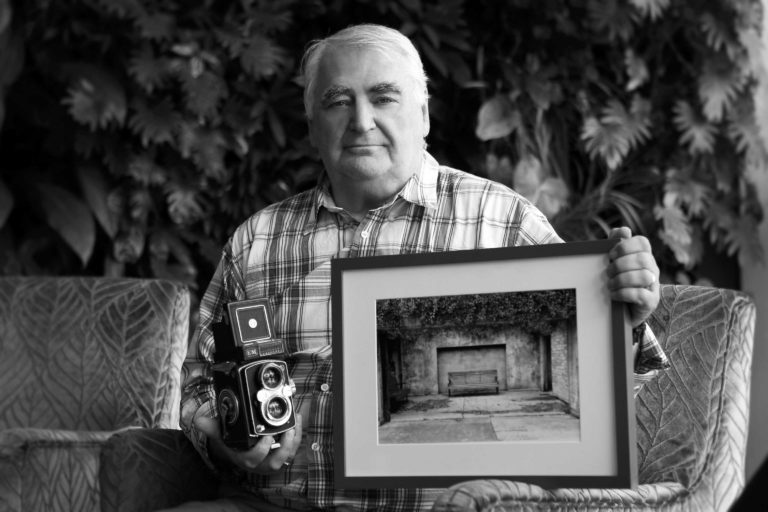

Richard McLaren, 70, grew up in NSW and now lives in Ipswich. He joined the Air Force in 1966 when he was 20 and served in Vietnam in 1969-1970. He tells ORM about his experience, the affect it had on him, and how photography became his therapy.

“The year 1965 was a difficult one for me. My father died suddenly, I got married and had my first child. I think that’s when I started running away.

I joined the air force in 1966 when I was 20 years old. I became helicopter crewman in 1968, I was looking for adventure.

I spent nine months in Vietnam between 1969-1970, stationed at Vung Tau. I’d been married for four weeks before I went to Vietnam. On the flight, heading out to Vietnam, I felt excited. I was looking forward to doing what we had been trained to do. I had a lot of respect for what we were doing and we did the job well.

It was scary at times, intensely sad at others. It became a problem when I realised we really shouldn’t have been there at all. It was not a fight we should have been involved in. It was an internal fight between the north and south, and Ho Chi Minh wanting unification for his country.

We avoided talking at night about what had gone on during the day. There was a lot of drinking, as there was little else to do and the booze was cheap. Some entertainment was provided, movies and some visiting entertainers to keep us occupied.

We’d head into town and go around the bars. Beer was the favourite but I drank scotch with coke which cost 5 cents. It served a purpose.

During the day we did what we were asked to do. We had briefings each day and most of the day was flying around the country. We did SAS insertions and extractions, troop insertions and resupply, ferried wounded to hospital and more. We worked with the local military and we worked hard.

There was no phone communication for us to contact family so it was constant letter writing to home. My wife wrote regularly. Her brother was in the army and was in Vietnam at the same time as me. I was able to keep in contact with him up there, which was good. Letters from home were very important to our moral.

I was enjoying doing my job until about three months in when I realised they were shooting back and they wanted to kill us. It changed everything. Suddenly we felt unsafe, as we didn’t really know who the enemy was.

There were a few alarming incidents. A lady who did our laundry during the day was shot trying to sneak through the airfield perimeter at night. It transpired she was Viet Cong by night and doing our laundry by day. Another included children in the streets carrying newspapers, covering grenades in their hand to throw at servicemen. You had no idea who you could trust. It was, in fact, terrifying.

At one point, about three months in, our supply ship, the Jeparit was halted at the docks by strikes and moratorium protests, so all our supplies were held up in Melbourne; everything from ammunition to food and mail. All the stuff we looked forward to. We went 10 days without – that’s a long time when you’re waiting for things you need.

One day I was called into my Commanding Officer’s office and told I was going home the following Tuesday.

“I still have 100 days to go,” I said. “I want to serve out my twelve months.”

I was told my wife had been in touch with the air force back home, was having a lot of difficulty with me being away and the decision had been made to send me home.

I felt extremely humiliated.

You have no idea how difficult it was to go back to my mates and say, “My wife wants me home, and I have been ordered home. I have to go.”

My colleagues didn’t say much but I could tell by the way they spoke to me they weren’t impressed. It made life very difficult in the last couple of weeks in Vietnam. I felt incredibly guilty for letting my friends down. The whole feeling was exacerbated when we got home.

When I was leaving Saigon, there was a rocket attack on the other side of the airfield while we were taking off. It was a quiet trip home.

At 8pm I was back in Sydney, in the arms of my wife with no military instructions about what to do now, you literally returned to civilian way of life 10 hours after leaving a war zone.

All the adrenaline, everything I’d felt for all those months, was supposed to stop at the end of that plane trip. It’s hard to describe how difficult that was. Everything in Vietnam was so intense. We’d spent months not feeling safe, when suddenly I was back home in Moss Vale.

My family didn’t want to talk about what I did in Vietnam. They told everyone else that I didn’t want to talk about it when in fact, I was screaming to get it out. Vietnam veterans were rejected by friends, family and the whole community.

I went to my local RSL and was politely asked to leave. I wasn’t welcome because I was a Vietnam veteran. This wasn’t a war we had won.

I left the air force in 1971, I thought I’d made the right decision not to re-enlist but 40 years later, I’m not so sure about that.

I had 16 jobs in 10 years. I worked in insurance, was a plumber’s labourer, sold furniture and set up my own window cleaning business among other things. I was trying to find something that made me feel fulfilled. Something was happening to me, but I didn’t know what. My marriage broke down.

I had another marriage and that fell apart too. One day I was driving in Newcastle thinking I was on the main street in Gosford. It frightened the heck out of me. I felt I’d lost control of my mind.

My local doctor referred me to see a psychiatrist in Goulburn. I didn’t get much out of the conversation but I asked at the end, “How do you think I’d go at university?”

“You’d excel” he replied.

I was given the number for Griffith University in Brisbane. I did a three-year business degree. I taught in Tafe for four years. University was very fulfilling and teaching felt great for a while.

I didn’t go to a therapist until 1994. I was trying to work out what the hell was happening to me. I was depressed, anxious, I had severe lack of concentration, I was a mess. But I refused medication.

It was at that point that I had a breakdown. I was nearly 48. I argued with my doctor when they diagnosed PTSD.

I met my current wife, Karen, while I was being diagnosed with PTSD. I did an intensive Combat PTSD course to find out more about it. They couldn’t give any advice on how to treat it. They said it was incurable.

It was then that I realised I had to find a way to deal with it myself. Suicide was an option but I didn’t go through with it.

I took up photography. I took photos of everything and anything that looked good.

In 2004, I was the photographer for Brisbane Writers Festival for the week. It was great! I made some good friends amongst the authors and some bought the photos I’d taken of them.

For the next three years I did Brisbane and Melbourne Writers Festival. I looked forward to them all. In 2007 at one festival they had a group of intellectually handicapped people presenting poetry. One lad couldn’t control his body and couldn’t speak apart from some noises he’d made into his own language.

They read some poetry he’d written. It was incredible. He wrote about life. There were mentions of flowers, trees and lots of colour.

I wondered how he would go trying to take photos of what he was writing about. I was introduced to his carer and his father who worked for disability services.

I started a photo workshop for people with disabilities, two hours per week for six weeks. At the end of each course I chose the best photos, blew them up and put on an exhibition at Brisbane library.

I’ve now done 40 courses. I realise it’s my therapy. I did six courses last year; four with mental health sufferers, two with refugees down in Logan. I showed them that language wasn’t a barrier; you can speak to everyone through a photo.

It was amazing to see the look on these people’s faces when they were taking photos. I helped one girl press the button on the camera. It was the first time she’d ever had a camera in her hand. I helped her take her first photo. What an incredible feeling that was and the sheer joy in her eyes.

At the beginning of each course I talk about my PTSD, my experience. There is an instant trust as they know I understand what they are feeling and going through.

At the end of each day I go home to my wife and we would talk about the course. We have relaxing weekends. She knows what it’s doing for me and she couldn’t be happier about that.

Two years ago I took Karen to Vietnam and showed her all over the country. I’d been back once before and still had issues with it. This was her first trip out of Australia ever; it was just as much fun watching her as seeing everything else!

It was interesting to see people progressing with their lives there. I came away feeling I have no qualms about Vietnam anymore. I got my own closure in my own way, in my own time.

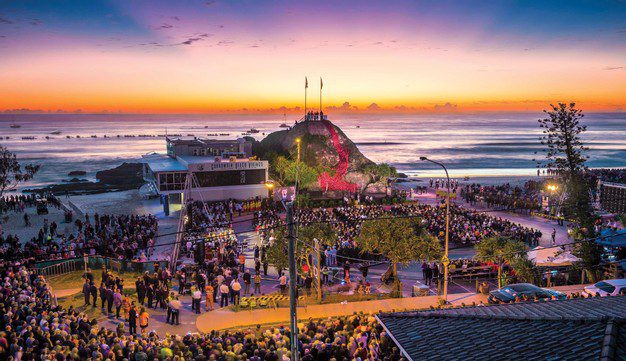

I was in a documentary about PTSD and the premier was at Currumbin RSL. They were able to fulfil my desire to photograph the Currumbin Dawn service that year.

I was so impressed with the way they operate down there that I joined them and their staff’s fantastic. They’re caring, they communicate with the members and they have the welfare of veterans at the forefront of their minds.

Anzac Day to me now is about remembering. I don’t like going to marches. My mind is on those who can’t make it, and with the families of those we lost in the conflict and since. It’s an emotional day. I’ve learnt to accept that it’s an emotional day; I stay at home and do what I need to do.

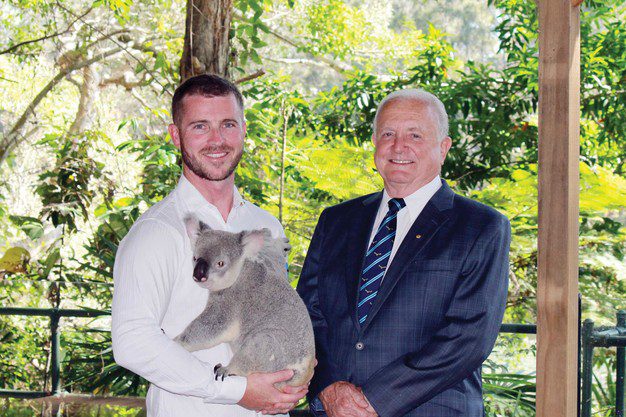

I enjoy attending 9 Squadron reunions. It’s good to see people you haven’t seen for years. At a recent reunion, I met up with a friend I hadn’t seen for 40 years, and who I served with in Vietnam. The relationship you form as friends and comrades in a war zone, is ever lasting.

When we came home we all went our separate ways. We probably hid from things for a long time. Some still are hiding and now it is happening to the more recent service men and women

Now, I’ve found a way of life that works. I have good days, some not so good. It’s certainly still there. I get emotional very quickly and I still have problems concentrating.

Currently I am working with former test bowler Tony Dell who has set up a fantastic organisation, Stand Tall for PTSD. He held the first forum of its kind for people with PTSD in 2015 and it’s an honour for me to be their honorary photographer for all their events and functions. The next one’s in September, PTS 17. I’m getting some veterans involved from here and Canada to create a photo exhibition at this event. We’re going to look at what they consider recovery to be from PTSD, through photography. I’m looking forward to that.”

HOW YOU CAN HELP

Symbolic sleep out at Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary

Currumbin RSL’s Anzac Day service has become an iconic Queensland event.

This year, it has again joined forces with major supporting partner National Trust Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary to offer a symbolic sleep out on the Eve of Anzac Day, in the grounds of the sanctuary itself.

In 2015, the event was a sell out. The entire 100 per cent of profits from ticket sales this year will go direct to veteran’s welfare.

The Anzac Day dawn service at Currumbin, held at Elephant Rock, is one of the largest gatherings in the country.

When: Monday April 24.

Tickets: 500 tickets are available for the sleep out. Includes a designated car park.

Guests: will experience a night under the stars sleeping in swags. When they wake up in the morning it’s just as stone’s throw away to the service.

Monday: access to sanctuary from 12pm. Evening includes entertainment for young and old. A short documentary will be screened and veteran interviews will take place. Kids can play in ‘Critters Craft’ area. There will be a ‘Wondering Wildlife Experience’ and the movie ‘Gallipoli’ will be shown on the big screen.

Anzac morning: up at 3am, small snacks and water provided free of charge. Short guided walk to the Dawn Service.

More info tickets: www.AustraliaRemembers.com.au