GOURMET

Vegans, hippies, and the bearded crew!

WORDS: PHOTOGRAPHY

As society becomes increasingly health conscious, many have questions around wine itself. Here’s ORM’s insight into organic choices, why there’s a growing trend toward them, and what to choose.

With a rising consciousness of all things healthy, land care, sustainability, the minimal use of chemicals, and a focus toward a healthy lifestyle, the subject of organic and biodynamic farming resonates with the community.

It seems obvious really that sustainability in winemaking and the notion of ‘green’ wine (organic and biodynamic wine) has appeal in this part of the world. One senses green wine serves to complement nature, our personal wellbeing and positive lifestyle choices. Green wine serves our earth mother instincts well.

As Max Allen writes in his book The Future Makers: Australian Wines for the 21st Century: “I believe we carry within us an archetypal idea that wine is a natural product of the earth, just grapes grown naturally, fermented naturally. We would like to think that the wine we drink has not been buggered around too much, if at all.”

One only need look around our local suburbs and towns to see flourishing growers’ markets and to witness a farmer’s pride and joy toward caring for the land and producing wholesome foods.

The same applies to wine.

Visit a cool bottle shop to see a section devoted to organic/biodynamic/natural wines, or notice the increasing amount of organic and biodynamic wines on restaurant wine lists.

Defining organic and biodynamic wine

Green wine may sound like a concept for the vegans, hippies, and the bearded crew, but for me it involves taking a sustainable approach to viticulture (the growing of vines) and the subsequent making of wine using the organic and biodynamic principles of farming as identified by Rudolf Stenier in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Rudolf Stenier was an Austrian-trained scientist and philosopher who founded ‘biodynamics’. He was the first scientist to publicly state that farming land needed special care and that prolonged use of synthetic herbicides, pesticides, and fertilizers caused a rapid decline in the health and fertility of a farm’s soils, plants, and animals. He was also the first to identify that a farm is a single self-sustaining organism that thrives through biodiversity and the integration of crops and livestock to be a closed-loop system of fertility.

Enter biodynamics.

Specifically, organic and biodynamics are varied yet similar approaches of two ideals requiring clarification. Wine Australia defines organic viticulture and winemaking as “grapes grown and processed using no synthetic or artificial additives, chemicals, herbicides, pesticides, fertilizers or genetically modified products or organisms”.

Simply put, it is what actually happens at the vineyard — and not necessarily what happens in the actual winemaking process. Organically-farmed vineyards also rely on natural treatments or homeopathic-type treatments to treat the soil and plants. Be good to the land, and plants and livestock will flourish.

Interestingly, prior to 1847, all wine produced would have been organic due to the absence of synthetic chemicals and fertilizers.

On the other hand, the official definition of biodynamic farming, according to the Biodynamic Farming and Gardening Association, is “a spiritual-ethical-ecological approach to agriculture, gardens, food production and nutrition”.

In particular, biodynamic farming and the making of wine takes on a holistic approach where the same principles of organic practices are applied but also the vineyard is treated as a single ecosystem encouraging the regeneration of micro-organisms in the soil, using tools and techniques derived from the vineyard itself.

Essentially, biodynamics takes cues from the lunar cycles, which determine the best times to harvest grapes, prune, and irrigate, and when to leave the vineyard alone. If this sounds a bit hippie, think for a moment how tides are influenced by the lunar cycle (high and low tides and so on), as is the moisture in soil.

The lunar cycle outlines four, three-day periods called fruit day, which is best for harvesting; root day, which is the best day for pruning; flower day, which is best for leaving the vineyard alone; and finally leaf day, which is ideal for watering plants.

Homeopathic preparations are extensive in biodynamic farming. Wine Folly identifies nine compost preparations, which include everything from “manure and cow horns to yarrow blossoms (mentioned in Homer’s Illiad for treating wounds), chamomile (a natural antiseptic) and stinging nettles (a natural cleanser). Of course, there is no serious evidence on whether or not cow horns are a truly necessary component in what is ultimately a dedicated organic gardening process”.

But there you go — cow horns and biodynamic homeopathies. I can just see vegetarians cringing at the thought. Biodynamic farming is not limited to such preparations but also relies on animals such as sheep to eat weeds or by growing special flowers between each row of vines as a form of controlling weeds by natural means.

Some winemakers actually play music to the vines to ensure plants grow rigorously and healthy. Check out the vineyard DeMorgenzon from Stollenbosch if you think I’m joking.

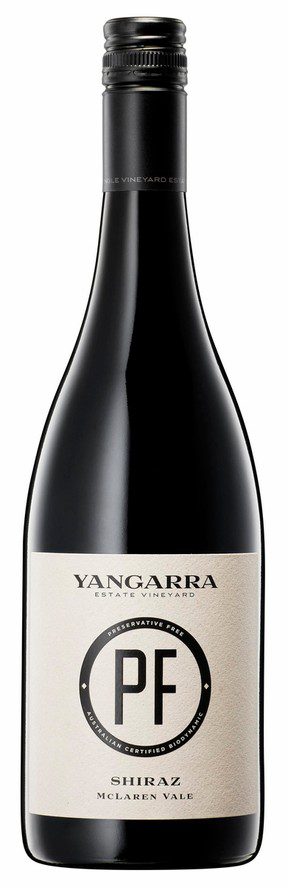

Is it preservative-free?

Is organic and/or biodynamic wine preservative-free? The answer is no, not necessarily. Sulphur dioxide (preservative 220) quite often occurs naturally in wine production. However, in both organic and biodynamic wine, added sulphur is permissible but is kept exceptionally low, with levels ranging from 25–75 parts per million (ppm), sometimes higher, but not as high as non-organic/biodynamic wines, which have up to 500 ppm or more.

The use of added sulphur in wine is always a bit controversial, but by contrast many naturally dried health food fruits and foods for example contain much more sulphur than wine. Some dried fruits may contain as much as 3000 ppm.

Likewise, our busy streets contain more sulphur than in a bottle of wine. Note the addition of sulphur is not a new thing in winemaking, but rather has been used over thousands of years to protect wines against spoilage.

But what does it all mean?

I get asked for vegan-friendly wines regularly — so why is grape juice not vegan-friendly?

Simply because clarifying cloudy wine (all wine is cloudy to start with) undergoes a fining process. This fining process usually involves using agents such as fish bladder proteins, egg whites (like chefs use to clarify consume soup), or other animal proteins to remove the cloudy haze in wine, thus making the wine non-vegan-friendly.

Vegan-friendly winemaking techniques use clay or charcoal to remove the cloudy haze by capturing all the particles and dropping them to the bottom of the tank. Another technique is to not filter or fine the wine at all, thus leaving the wine cloudy and, of course, vegan-friendly.

Natural wines

There is no official definition of ‘natural wine’ per se. To even suggest that wine is either made natural or unnatural is controversial in itself and ambiguous to say the least.

In an article published by The New Yorker on 18 November 2019, author Rachel Monroe raised a good point that “to call it natural (wine) is merely to make a general claim of virtue”.

“Specifically, what people mean when they declare a wine to be natural, then, depends on a constellation of factors: the soil, the grapes, irrigation or its absence, the harvest methods, the amount of sulfur, what machines were or were not involved — even, perhaps, the winemaker’s personality and politics, and where and how the bottles were sold. There are many ways to be virtuous, or to fail at it.”

The movement began in the 1960s in France, and in Beaujolais of all places.

Wiki states: “Some fans insist that natural wines must have zero sulphites added, while for others some addition at bottling stage is allowed. In any case, the total amount of sulphites present in a natural wine is significantly lower than in ‘non-naturally’ produced wine. Most agree that the grapes used must come from organically grown vineyards (certified or not), and that only wild or indigenous yeasts be used to ferment the juice (as opposed to a laboratory-produced cultivated yeast strain).”

Further research would suggest that grapes should come from dry blocks that have not been artificially irrigated and are naturally low-yielding, with no mechanical harvesting or additions to the wine such as acid, tannins, or added sugars, with minimal filtration and oak ageing.

For me, it’s just wine — sometimes stinky, sometimes clean, sometimes cloudy, sometimes clear, but usually bottled, with a catchy label. Will this trend continue like ripples in a pond or fade and die like a beautiful flower — the jury is still out.

Orange wines

Orange wine is not made from oranges. According to Wine Folly, “orange wine is a type of white wine made by leaving the grape skins and seeds in contact with the juice, creating a deep orange-hued finished product”.

Wine Folly states: “To make an orange wine, you first take white grapes, mash them up, and then put them in a large vessel (often cement or ceramic, but not always). Then, you typically leave the fermenting grapes alone for many days or longer with the skins and seeds still attached. Orange winemaking is a very natural process that uses little to no additives, sometimes not even yeast. Because of all this, they taste very different from regular white wines and have a sour taste and nuttiness from oxidation.”

I’ve tasted some rippers, including Cullen’s Amber, which is made in amphora (ceramic wine vessels) and Whistler’s Back to Basics Skin Contact wine, which is cloudy and vastly different to the pristine style of Cullen. Both are delicious and definitely orange in colour!

But what about minimal-intervention wines?

Where you hear or see the use of the term ‘minimal-intervention’ wines, the scholarly view is meant to mean all of the above. Many would argue that natural wines and minimal-intervention wines are one and the same.

For me, the term minimal-intervention wine is less controversial than using the words ‘natural wine’. By now, I’m hoping you have gathered that all of the abovementioned points about these wine types preferably use traditional winemaking techniques and incorporate organic principles.

For the most, they are going to look differently and smell and taste differently to more conventional wines. In my opinion, to get the best out of these types of wines, decant first, use big and wide open-style glasses, and give the wine plenty of time to air.

Is it certified?

Not all wines claiming to be organic, natural, minimal-intervention, or orange are certified organic. Personally, I look for the certification on the back label of the bottle. They are the real deal.

Certified organic wines follow strict rules and guidelines and are only certified after a three-year assessment period. Once certified, a vineyard is assessed yearly in order to retain certification.

A recent article written by Daniel Honen and appearing in the Guardian states: “There are two prominent organic certifying bodies in Australia that most winegrowers will use to prove that their wine is organic. These are Australian Certified Organic (ACO) and the National Association for Sustainable Agriculture, Australia (NASAA). Look out for the particular certifying body’s logo, which, in most cases, will be printed somewhere on the wine label. This is your assurance that what you’re drinking is actually organic.”

Certification can be costly, especially for small producers, but hats off to the wineries that meet both the rigours and costs of certification. Look for either one of the logos and take comfort in knowing they are genuine organically-certified wines. Also be mindful that organic/biodynamic certifying bodies and their logos will be different from other countries.

About the author

Peter Panousis works for Mezzanine Wine. He has a degree in hospitality, is WSET-trained and has undertaken extensive wine education. Raised on the Gold Coast, Peter is an experienced operator of restaurants and cafes, which has included owning two award-winning restaurants. Peter is also a member of the Australian Society of Viticulture and Oenology (ASVO) and an Associate Fellow with the Australian Institute of Management (AIM).

You can catch Peter on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram @peterpanwine