PEOPLE

Inside NevHouse

WORDS: PHOTOGRAPHY

Nev Hyman is making waves in the sustainable affordable housing industry. ORM caught up with him to talk about his journey from making surf boards to making houses.

Nev Hyman speaks with a missionary zeal. Which is fitting, given he’s a man on a monumental mission to help save the planet and house the world’s poor.

After more than four decades as one of Australia’s top surfboard shapers, Nev is now making waves in the sustainable affordable housing industry, turning plastic waste into homes for the homeless. With about 380 million tonnes of plastic produced worldwide each year — and an estimated eight million pieces of plastic finding their way into our oceans every day — it’s a noble cause indeed, particularly when you consider that more than one billion of the world’s population are also homeless.

It’s been one helluva ride for the red-haired surfboard shaper turned eco-social warrior and the man who’s been dubbed a ‘Ginger Genius’— from the peaks of making boards for some of the world’s leading surfers to the troughs of a near-financial wipeout a few years ago. Now he’s riding high on the crest of his latest venture, NevHouse. He’s also back in the shaping bay, making retro replicas of boards he made for some of his champion team riders back in the late 1970s and 1980s.

ORM catches up with Nev in one of the two neighbouring villas he owns at The Glades golf course at Mudgeeraba (surfing and golf are his two passions). He lives in one villa and uses the other as an office, and we take a seat in the garden of the latter overlooking the 18th hole for a chat.

Nev began his surfboard manufacturing career in the early 1970s in his native Western Australia, starting out at the age of 13 working in surfboard factories.

“I did everything from sanding, glassing, and ding repairs through to (later) shaping,” he says. “That taught me my craft.”

Nev made his first boards in the garage of his Perth home in 1972 and established his own label the following year. After four years with WA outfit Odyssey Surfboards in the mid-1970s, he headed across the Nullarbor and up to the Gold Coast where he set up Nev Hyman Surfboards at Burleigh Heads. It later morphed into Nev Future Shapes, which went on to become one of Australia’s most iconic surfboard brands, with a stable of team riders including enigmatic Queensland and Australian champion Peter Drouyn and star pro surfers such as Michael ‘Munga’ Barry, Sunny Garcia, Danny Wills, Nicky Wood, and Trudy Todd.

From Burleigh Heads, Nev moved to Mermaid Beach where he established a landmark factory-retail outlet on the Gold Coast Highway, churning out thousands of boards a year for the domestic and export markets. Ever the entrepreneur, he built a giant surfboard and made it into the book of Guinness World Records when 45 surfers rode the behemoth at Snapper Rocks. He was one of the pioneers of computerised surfboard shaping, which turned the industry on its head in the early 1990s.

In 2006, Nev really took his business into the future, establishing Firewire Surfboards with partners including former Billabong surfwear company executives Matthew Perrin and Dougall Walker and pro golfers Adam Scott and Ian Baker-Finch. Using a revolutionary epoxy manufacturing process, the business set out to mass-produce lighter, stronger, and greener surfboards. The company’s team riders included 11-time world champion Kelly Slater and other top professionals such as Taj Burrow, Michel Bourez, and Sally Fitzgibbons.

In 2014, Nev sold his majority stake in Firewire to Slater.

“I’m still a passionate advocate for Firewire, and it’s still my board of choice, but I’m no longer involved in the business,” he says.

Dismayed at the amount of plastic pollution he’d seen in the ocean during his years of world travels surfing and shaping — particularly in places such as Indonesia — Nev had invested heavily in a plastic recycling/wood replacement business in 2009. He admits the investment caused him to take his eye off the ball at Firewire, and his relationship with the company began to suffer.

“It was my fault — it all looked glossy from the outside, but I was putting the company, my wife and family through a lot of pain,” he says.

“In 2012-13, I was in a dark place in my life. I was pretty much flat broke and travelling back and forth to Indonesia trying to get the wood replacement business going because my [business] partner had died. I spent seven months in Jakarta and then I got dengue fever.”

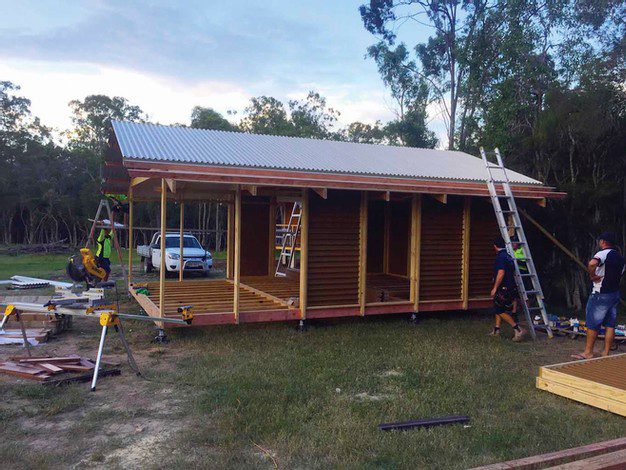

Unable to secure funding — “I realised selling wood replacement products wasn’t sexy enough” — Hyman dumped the technology and, together with experts including Sydney architect and fellow surfer Ken McBryde, came up with a concept for cyclone-proof, modular homes made from wood plastic composite and laminated sustainable timber.

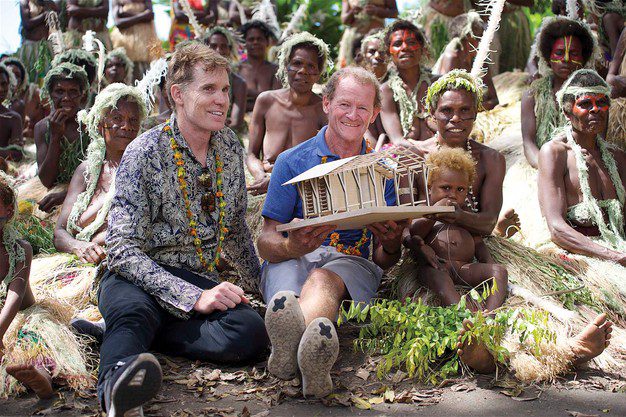

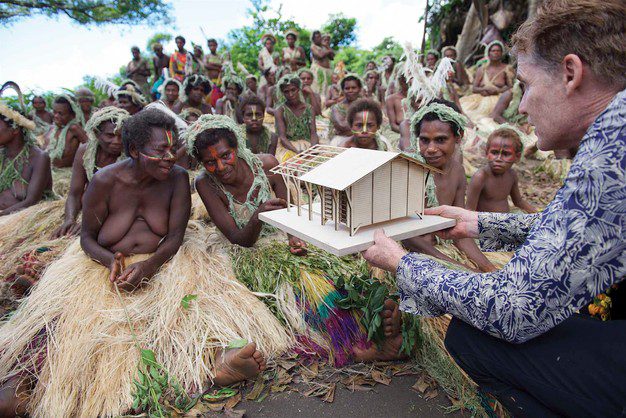

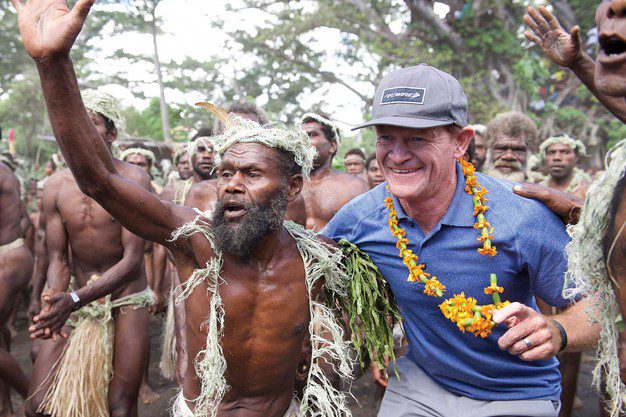

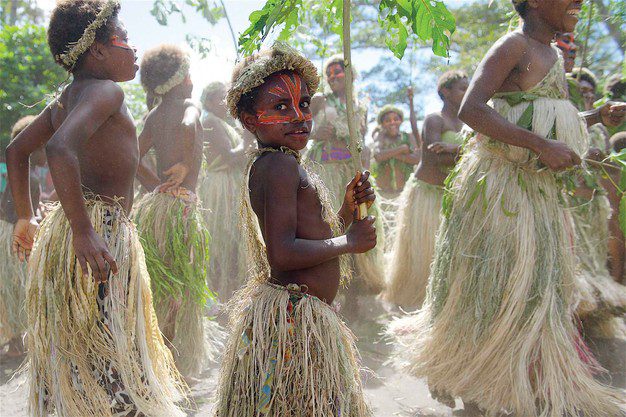

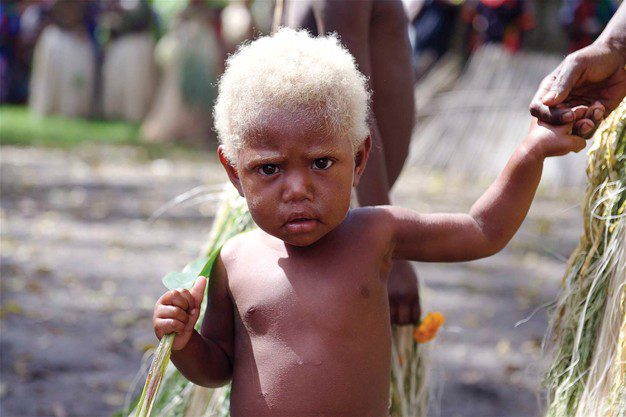

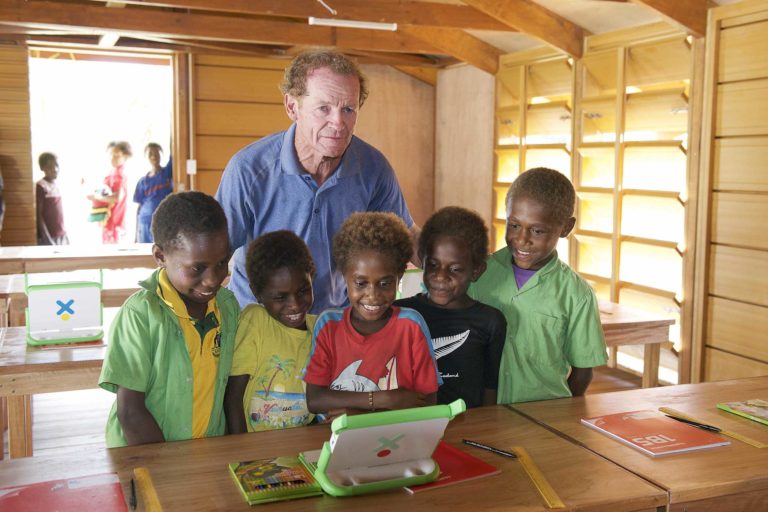

The technology was used to build 15 structures — classrooms, community centres, and medical facilities — on remote Tanna Island in Vanuatu after it was devastated by Cyclone Pam in 2015.

For the first time in living memory, the 12 tribes of Tanna, sometimes fierce rivals, came together for the NevHouse dedication ceremony, sacrificing 12 pigs in Nev’s honour.

Nev says the Vanuatu Government engaged NevHouse to deliver another 1500 structures, but reneged on the deal.

“The corruption in the government made it impossible,” he says. “It set us back financially; it set us back emotionally. We did everything we possibly could do.

“Last year, a member of the government got the contract to build 100 classrooms out of tin. That’s going to cost lives, mark my words. The next Category 5 cyclone that hits Vanuatu is going to kill people. If that happens, in a place where we were going to deliver safe houses, I’m going to kick up a real stink. You’ll see me on 60 Minutes.”

Despite the setback in Vanuatu, Nev still managed to win over Prince Andrew to be crowned global winner of the Duke of York’s Pitch@Palace global entrepreneurship competition — designed to match start-up businesses with investors — at St James’s Palace in London in late 2017. NevHouse beat 25,000 other businesses from around the world to claim the award.

“I love the ocean, but we have a problem,” Nev told the palace audience, which included the prince himself as well as business investment heavyweights. “The problem is plastic. And we also have another problem: the desperate need for affordable shelter around the world.

“What is the biggest business on the planet at the moment? I believe it is affordable housing.”

NevHouse is now working to move into countries including Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Mozambique, Honduras, and Mexico to supply housing and also establish waste recycling facilities known as NERFs (Nev Earth Resource Facilities).

“I’ve met with the president of Honduras and the president of Mozambique,” Nev says. “In Maputo [the capital of Mozambique], 17 people were killed earlier this year [2018] when a huge garbage landfill collapsed in heavy rain and fell on them.

“Much of that rubbish was plastic, and I know for a fact that we can take three tonnes of plastic out of the environment to make one NevHouse. There’s not enough plastic on the planet to make the amount of houses we want to make. Plastic is not evil; it’s the improper disposal of it that is. But we have a solution.”

Nev says he has discussed his business model with “some of the smartest people in the world”.

“I’ve spoken with all the big waste management companies right around the world,” he says. “And nobody has said to me, ‘That’s a load of hogwash; it’s not going to happen’.”

Nev is also working to get NevHouses into Australia’s remote Indigenous communities. A pilot project has been established in Jilkminggan in the Northern Territory, with the aim to train up local Aboriginals to build their own prefabricated NevHouses.

“It’s a sad truth that it costs between $350,000 and $700,000 to deliver and build a 150-200sqm house in these communities, and it’s been like that for too long,” Nev says.

“We can build right now, with our current business model, the same house for $100,000, and we can build it in a matter of days.”

As well, Nev has held talks with the likes of Byron Shire Council about building affordable housing for millennials. And the company has just released to the public a limited edition NevHouse model, known as the Eco-Studio, for uses such as granny flats, art or yoga studios, and retail or commercial spaces.

Between travelling the globe on his NevHouse crusade, Nev is also back in the surfboard shaping bay, recreating hand-shaped, limited edition boards from the 1970s and ’80s ridden by his former team riders including ‘Munga’Barry, Peter Drouyn, Sunny Garcia, and Christian Fletcher. He has kept all the templates and measurements from that golden era of Nev Hyman Surfboards and Nev Future Shapes.

“I don’t want this to be seen as me going back into the surfboard industry, because I’m not,” he says. “All I’m doing is going back to my craft. Over the years, I’ve had so many people who’ve come up to me all over the world saying, ‘I had one of your boards when I was a ‘grom’ back in ’82; it went unreal; I’d love to get another’. The boards of the 1980s are just as good as the boards of 2018, without a doubt.”

Nev plans to give his former team riders a cut of each surfboard he sells “because these guys deserve every little thing I can do for them”. He also hopes it might create a new niche market for old surfboard master craftsmen whose talents have been largely lost to technological advances and mass production.

“It’s about investing in a master craftsman’s art, paying them their dues, and getting a really nice, hand-shaped surfboard to either surf or just hand on the lounge room wall,” he says.

“I’m hoping this little business model will enable some of these guru shapers the chance to make some money and allow washed-up surfers who understand and appreciate surfing history to go back to their happy place.

“I know I’ll cop some flak because I’m the bastard who was mainly responsible for the advent of computer shaping, but this is about going back to my roots and trying to give value to our craft.”

Nev says his involvement with NevHouse has taken him “outside the bubble” of the surfing industry.

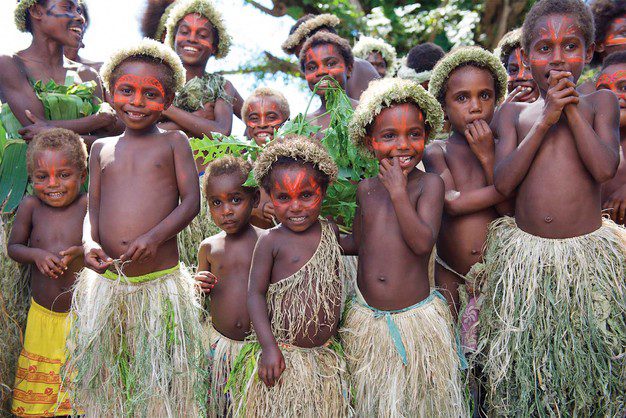

“I’ve had a very charmed life because of surfing, but it’s nice to be outside the bubble,” he says. “I’ve been to remote villages that have never had electricity, a hospital, or a medical clinic. People die just trying to get from A to B.

“To experience the joy of delivering a NevHouse to these people and do something to help the environment at the same time is a special kind of feeling. And we haven’t even scratched the surface yet.”