PEOPLE

Dugongs, Pig & Wuru

WORDS: PHOTOGRAPHY

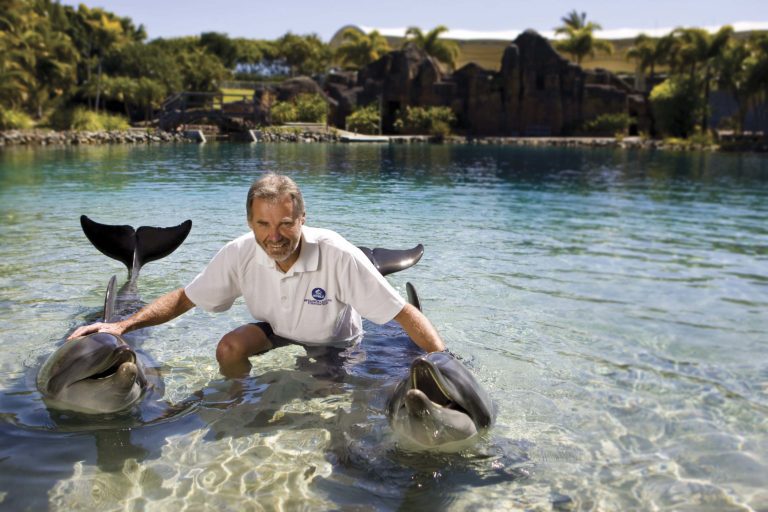

When the Sea World Research & Rescue Foundation started almost 30 years ago, no one could have imagined just how many rescues and research projects would take place there. In that time, the Foundation has run over 200 marine animal research projects and rescued many animals. Here, Trevor Long, who has been there since the very beginning, shares his stories and what are, for him, standout species.

The will to survive – physically, emotionally, financially – is acute and compelling, inextricably ingrained in our human condition.

I started working at Sea World more than 40 years ago. At the time the marine world was my yearning and I wanted to know more. Since then, I have seen many changes both good and bad in the marine environment; however, my love and appreciation of the marine world only continues to grow.

We started the Sea World Research & Rescue Foundation almost 30 years ago and since that time we have funded more than 200 marine animal research projects and rescued many animals. I feel a particularly strong connection with the animals we have had at Sea World and the many species I have been involved in rescuing. Dugongs are one of those standout species.

Dugongs are herbivorous marine mammals. In Australia they live around the northern half of our coastline, from southeast Queensland to Shark Bay in Western Australia, in embayments and other sheltered waters that support the seagrass meadows on which they feed. In Queensland, for example, significant numbers of dugongs live in Torres Strait and in Shoalwater, Hervey and Moreton Bays.

Globally, and along much of the urbanised coast of Queensland, however, dugong populations are declining and the species is classified as vulnerable to extinction.

A large adult dugong can be around three metres long and weigh between 500 and 600 kilograms. The calving season extends from spring to mid-summer, and there is a prolonged period of maternal investment. Newborn size varies within the range of 1-1.25m in length and 20-35kg in weight, and the single calf is thought to suckle from its mother for at least 18 months although it will also begin to eat some seagrass within a few weeks of birth. Dependent calves that are orphaned or otherwise become separated from their mothers would have little or no prospect of survival on their own.

In November 1998, a small dugong calf was found stranded at Forrest Beach, near Ingham in North Queensland. After being returned to the water and then found ashore again the following day, the calf was flown to Sea World in a light plane chartered by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. The male calf was at the lower end of newborn size range, being 1.09m long and weighing only 19.7kg. Although the aim of rescuing this young animal was to ultimately return him to the wild, having unsuccessfully tried to raise neonatal dugong calves on two previous occasions we were very unsure about his chances.

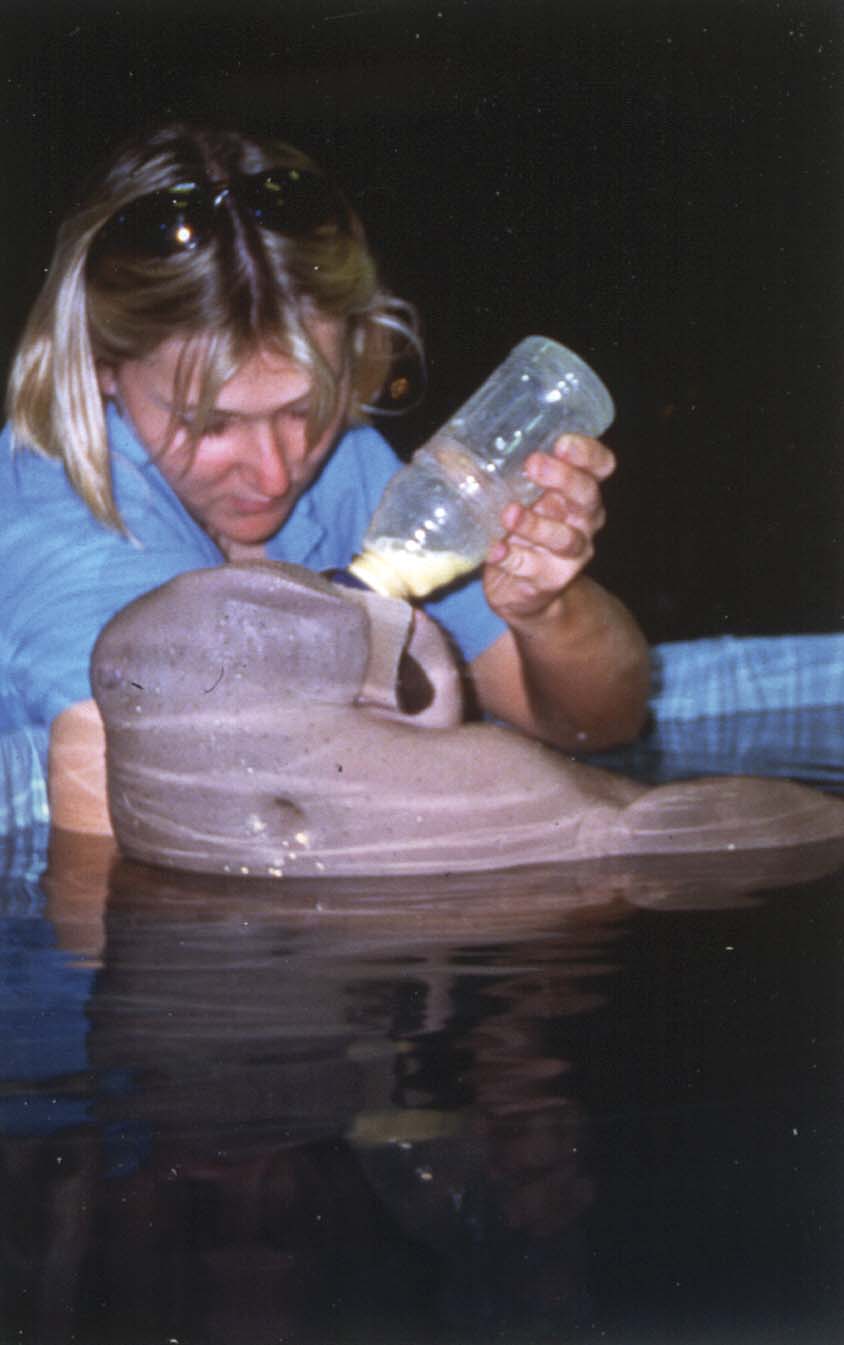

The calf was initially bottle-fed every two hours around the clock and required frequent veterinary treatment during the first two and a half months, after which his health stabilised and he began to make steady progress. Eventually nicknamed ‘Pig’, he continued to receive bottles of milk until he was fully weaned by 19 months of age and was eating an enormous amount every day. We took care to ensure that he would eat several species of seagrass preferred by dugongs, but for convenience and cost his staple diet consisted of a variety of salad vegetables.

As dugongs feed from the substrate, we had to design special feed plates that would anchor his food at the bottom of the pool.

Pig was the first neonatal dugong calf to be successfully hand-raised, and we had to carefully consider if a naïve juvenile could assimilate back into the wild environment. In November 2001 when just under three years old, he was transferred to a very large saltwater lagoon on the southern end of Moreton Island. Here, Pig was able to feed himself entirely on seagrass without requiring any supplementary feeding from us, and he remained in the lagoon for four months.

After this period, weighing 197.5kg, Pig was released into Moreton Bay. To assist us to monitor his progress post-release, he had been fitted with a satellite tracker generously loaned to us by dugong researchers at James Cook University in Townsville. This tracker was attached to Pig by a 3m long tether to a padded belt around his tailstock, which allowed the tracker’s aerial to come to the surface if he was feeding in shallow water.

A crucial part of such tracking harnesses is a weak link that would allow the animal to break free should the tracker or tether become entangled in anything in the environment (e.g. mangrove roots or fallen trees). Unfortunately, less than three days after he was released, Pig’s tracking harness washed ashore bearing scratches and cuts on the tracker and tether that clearly indicated it had been mouthed by a shark. His location and fate remained unknown.

Eight months later Pig was found near Kooringal Township at the southern end of Moreton Island, in a seriously malnourished state and with multiple injuries consistent with tusk wounds inflicted by another male dugong. He was taken back to Sea World for treatment, and placed in a specially heated rehabilitation pool in our Veterinary Quarantine Centre. He had lost more than 25 per cent of his bodyweight since release. Grave fears were held for his survival as his eating patterns and weight fluctuated, showing no steady pattern of improvement.

Many months into his recuperation, consensus grew amongst various stakeholders that it would be unjustifiable and not responsible to contemplate any future attempt to release him. Eventually, in August 2004, Sea World sought and was granted permission from the Queensland Environmental Protection Agency to transfer Pig on to Sea World’s Wildlife Exhibitors Licence. Pig lived at Sea World where he could be seen by the public to raise awareness of dugongs and threats to their survival.

The hand-raising techniques developed during Pig’s original rehabilitation proved useful, after the January 2005 stranding of another baby dugong near Rockhampton in central Queensland rescued from the beach by Queensland Marine Parks rangers.

Due to her weight and length, we estimated that she may have been between one week and one month old. We chartered a light plane from Coolangatta Airport and collected her the following day. Upon arrival at Sea World, when placed in a small pool she exhibited odd behaviour, immediately turning over on to her back and putting her flippers in her mouth. When she needed to take a breath, she would keep her body straight and simply roll over, then roll upside down again. She also passed blood in her urine for several days. Due to the nature of her injuries, we believe she had been struck by a small boat.

The condition and behaviour of the calf, now named Wuru, gradually improved until she was able to swim around the pool normally; however, she continued to sleep at the surface, and usually slept upside down (dugongs are supposed to sleep on the bottom, right way up). After 11 months, Wuru had still only ever slept on the surface of the water and because of this we considered that she would not be a suitable candidate for release.

We sought and were granted permission to keep her as a companion for Pig. In late 2008 came an opportunity to house Pig and Wuru in a much larger pool than was available at Sea World, and they now call Sea Life Sydney Aquarium home.

n Despite being iconic to Moreton Bay and heavily entrenched within indigenous culture, we became aware of the little amount of information known about this species. Together with The University of Queensland we now undertake a yearly health assessment of dugong in Moreton Bay. In the next edition of Ocean Road we will bring together a rodeo involving researchers, vets and many other stakeholders.

What can you do to help dugong?

Slow down on your boat or jetski, particularly when going through areas known to have a high population of dugongs and turtles. This will help to protect the animals and the seagrass meadows they feed on.