PEOPLE

Coaching the best

WORDS: PHOTOGRAPHY

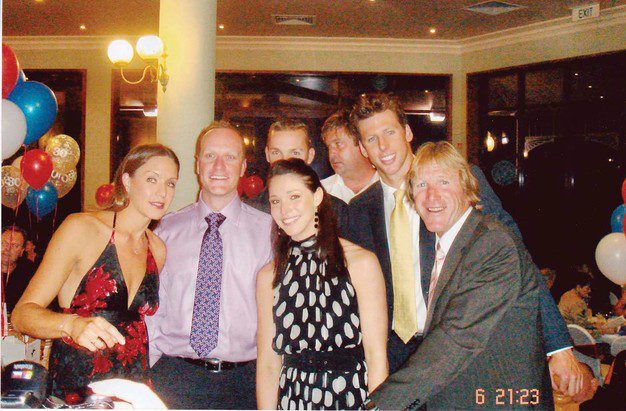

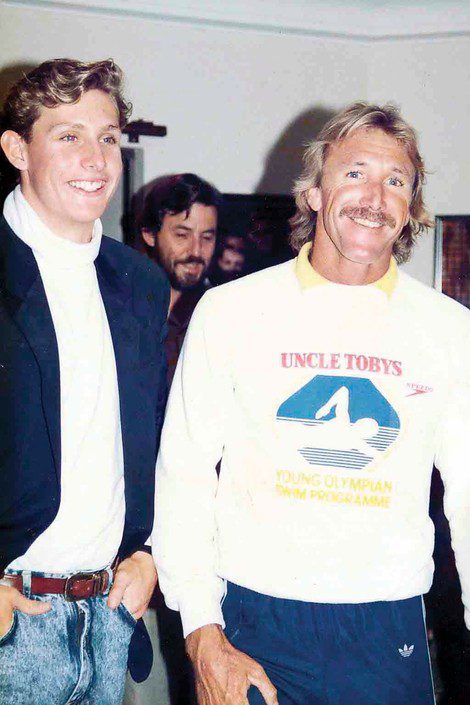

Denis Cotterell is the coach with the film-star looks who was once mistaken for Paul Hogan, the Australian actor of Crocodile Dundee fame, when he travelled to Canada with a national junior team. His bronzed appearance and blond hair are typical of those who lead the active life on Queensland’s Gold Coast, where Denis is also a member and coach of the Surfers Paradise Surf Life Saving Club. Many of his athletes swim for both the Miami Swimming Club and a surf club.

So went the story in SwimNews Online in a June 1998 profile on the Gold Coast swimming supercoach: his greatest swimmer, a still-gangly teenager named Grant Hackett, had won his first world championship in the 1500m five months earlier in Perth. Cotterell had already been coaching for more than two decades, having started at Brisbane’s Fortitude Valley pool in 1967. Looking back now on his career as he approaches 70, Cotterell has lost count of the thousands of swimmers he has coached, let alone the tens (perhaps hundreds) of thousands of kilometres they’ve churned up following the black line. Born in Brisbane, Cotterell started his working life as a physical education teacher after completing his degree at The University of Queensland. He worked at schools in Brisbane and the Gold Coast before a forced transfer to Gladstone saw him quit teaching.

“I was a surfie and didn’t want to go to a mining town,” he tells Ocean Road. Cotterell tried his hand at various jobs, including working on the railways, before taking up a coaching job at the Southport pool in 1971, working alongside the great Lou Vaughan.

“Things were getting a bit competitive between my team and his and I ended up getting the bullet after about three years,” says Cotterell, who was also working as a council lifeguard and nightclub barman to make ends meet. He ended up training his squad in the shark pool and waterski lake at Sea World where the father of one of his swimmers was a marine show commentator.

“It was a pretty interesting time,” Cotterell recalls. “Kids were getting cut up on oysters and getting splinters from the ski ramp swimming back and forth across the lake.”

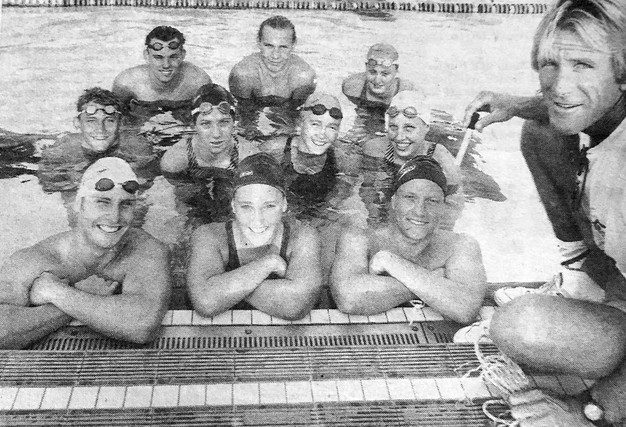

Cotterell also trained his squad at Tallebudgera Fitness Camp before being offered a job in 1976 at Miami Swimming Club, where swimming lessons, as opposed to elite coaching, were an early focus.

“The Gold Coast Bulletin really helped kick things along with a promotion of $10 for 10 swimming lessons,” he says. “I was teaching 40 to 60 kids myself and we had to get in an assistant.”

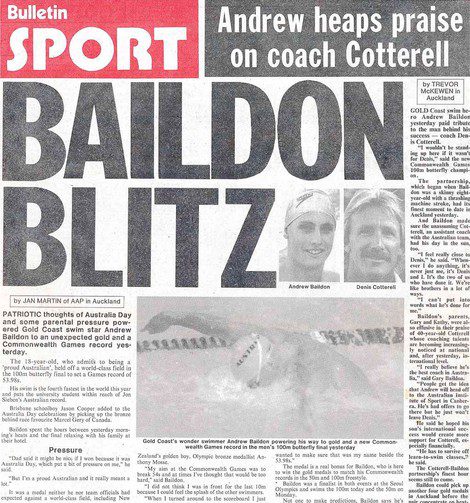

His first big-name swimmer was Andrew Baildon, son of Surfers Paradise newsagent Gary Baildon who would go on to become Gold Coast mayor. “Andy made his first [Australian] team at 15 for the Pan Pacific championships in Brisbane, where he was up against the two-time world record-holder [American] Matt Biondi,” Cotterell says.

Baildon won bronze in the 50m freestyle (in which another American, Tom Jager, won gold and set a new world record). He bagged four gold medals at the 1990 Commonwealth Games in Auckland and became the first swimmer in the Commonwealth to break the 50-second mark in the 100m freestyle. Baildon went on to represent Australia at the 1988 and 1992 Olympics.

But Cotterell remembers one of his most talented swimmers came along well before Baildon arrived on the scene. The Miami pool lessee’s daughter, Janet Rayner, was carving up the pool and “should have gone to the 1982 Commonwealth Games” in Brisbane, he says. “She was a great swimmer, but took up water polo and ended up captaining Australia and winning a gold medal at the 1986 world championships.”

Other top swimmers to join Cotterell’s squad included Olympians Jon Sieben and Daniel Kowalski and Angie Greenwood – mother of pop star Cody Simpson – who won the 1987 Australian 200m butterfly championship.

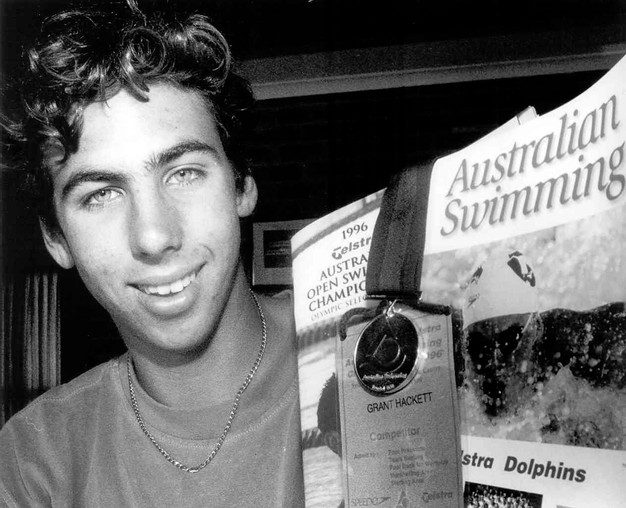

Then along came a kid named Grant Hackett.

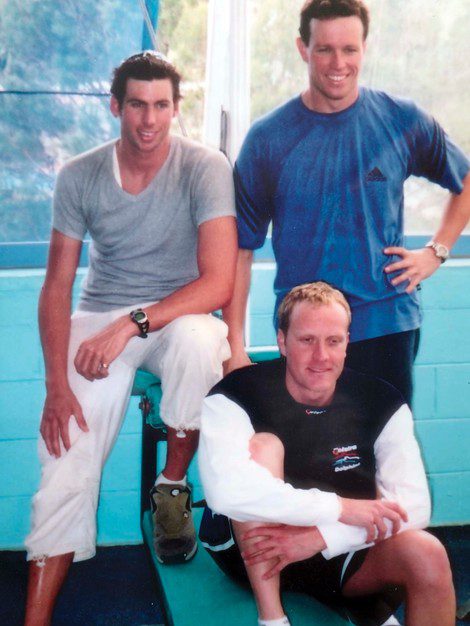

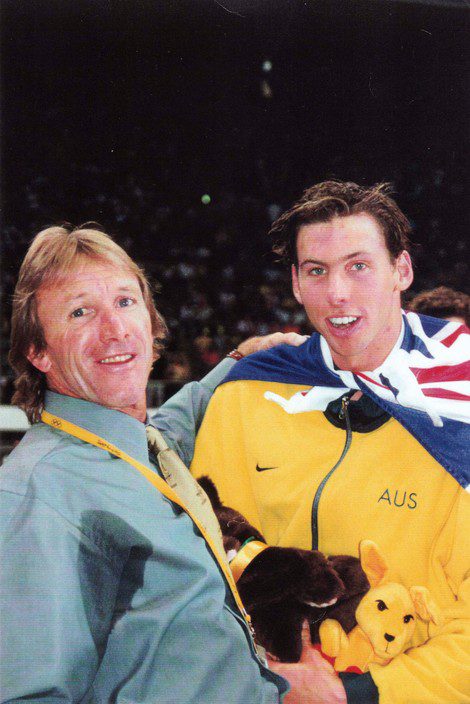

“Grant joined the senior squad at 12, but it wasn’t until after the Olympic trials in 1996 that he really decided to concentrate on swimming,” Cotterell says. “His brother [Craig] was doing well in the Uncle Toby’s ironman series and becoming a hero, but Grant had a different nature. And he was getting faster and faster in the pool.”

Cotterell still vividly remembers Hackett’s words after his first Olympic trials.

“He said to me, ‘I want to be the best in the world. I understand if I’m to be the best in the world, I have to be the best trainer’. And that’s exactly what he became. To this day, people ask me who was the toughest and it’s no contest – I’ve never seen anyone as tough as Grant.

“Plenty of people train quite hard, but he was something else. I was spoilt as a coach to have someone with his work ethic. He was his own worst enemy at times. He’d train when he was flat and make himself sick and lose half a week trying to get better. It was a bit of an Achilles heel for him. But you don’t want to soften that intensity in a swimmer.”

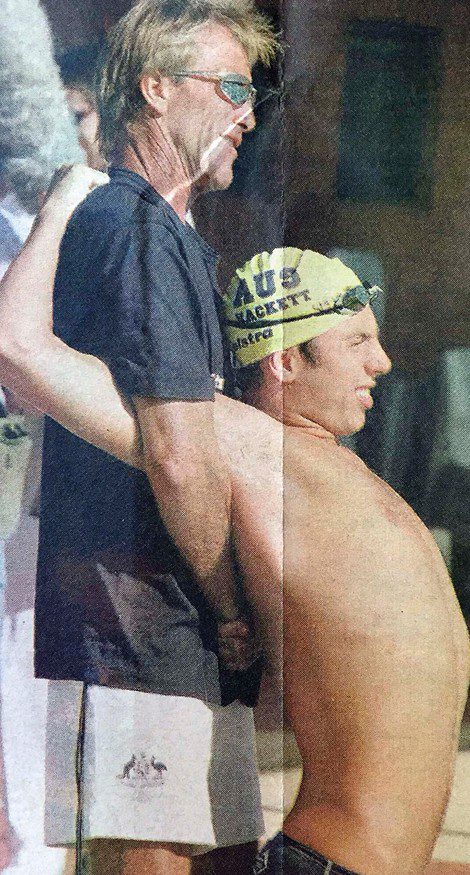

Cotterell says all of Hackett’s Olympic campaigns were beset by drama and sickness, “but he still prevailed”.

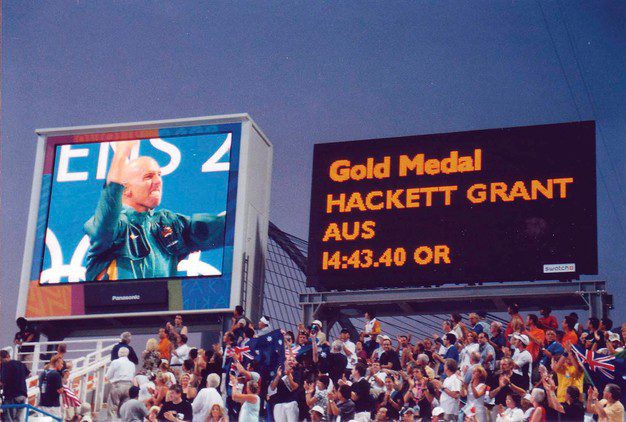

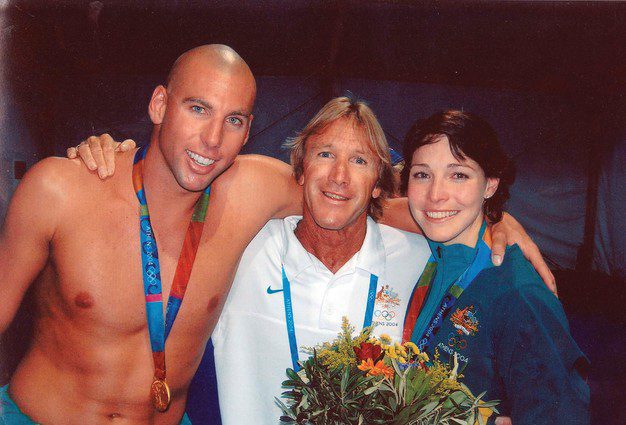

Hackett went into the 2000 Sydney Olympics battling energy-sapping, debilitating Epstein-Barr virus but out-swam reigning champion Kieran Perkins to win the blue-riband 1500m. At the 2004 Olympics in Athens, Hackett was again struck down by illness, but still powered to another 1500m victory over American Larsen Jensen and Welshman David Davies.

Cotterell remembers watching a panicked look come over Australian Institute of Sport swim coach Shannon Rollason as Jensen closed the gap and then caught up with Hackett with 100m to go. “I looked at Shannon and started laughing,” he says. “I said, ‘They’ll need a tank and a bulldozer to stop Grant now’. He ended up taking off and winning by a couple of seconds.”

It was later revealed that Hackett was swimming with a partially collapsed lung. Sadly for Hackett and his coach, he narrowly missed out on becoming the first male swimmer to win three successive Olympic titles in the same event when he finished with a 1500m silver in Beijing, behind Tunisian Oussama Mellouli.

“That was a real shame, because he deserved to win that race and make history,” Cotterell says.

Hackett’s downward spiral after his swimming career ended – culminating in his dramatic arrest at his parents’ Gold Coast home early last year as he battled booze and prescription drug problems and the fallout of a bitter bust-up with singer wife Candice Alley – distressed his former coach.

“You see it a lot in all elite sport – getting out of the game leaves a big vacuum,” Cotterell says. “A lot of sportsmen and women really struggle unless they can replace it with something meaningful enough. The longer you’re in the game, the harder it is to get out, and that was especially the case with Grant. Very few sportspeople have gone into battle against the world’s best year in and year out for as long as he did. He put himself on the line for 10 years and he was undefeated.”

Cotterell says Hackett, with whom he reunited for a comeback that saw him win bronze in the 4x200m freestyle relay at the 2015 world championships, now appears to have turned the corner after spending time with American superfish Michael Phelps in the USA and then relocating to Melbourne to be closer to his two children.

“Grant seems to be in great condition now, physically and mentally,” Cotterell says. “It’s really good to see. A lot of people don’t realise the esteem he is held in in the world of swimming – how much respect he has in and out of the pool from swimmers and officials through to heads of state who have wanted his autograph after watching him swim. People aren’t aware of his real position in the history of the sport.”

Olympic champion turned Channel 7 commentator Giaan Rooney was another of Cotterell’s favourite charges.

Rooney came to his squad at the age of 11, training alongside Hackett and Kowalski. She shot to fame at 15 when she won gold in the 100m backstroke and the 4×100 at the 1998 Commonwealth Games in Kuala Lumpur, but not before Cotterell came to the rescue with fried chicken.

“Giaan was just a kid and was feeling a bit sick in the [Games] village with all the international food,” he recalls with a chuckle. “She had pretty simple tastes and just wanted some normal food, so I went and got her some takeaway from this joint called Kenny Rogers’ fried chicken, believe it or not. I grabbed a box of that and some plain bread and took it to her and it put a smile on her face straight away. It lightened her mood.”

Rooney was also part of the Australian team that topped the medal tally at the 2001 world championships in Fukuoka, despite being sensationally disqualified, along with her 4x200m freestyle relay teammates, after jumping into the pool prematurely to celebrate their win. Cotterell says Rooney, who also won gold and set a world record in the 4×100 medley relay at the 2004 Athens Olympics, struggled with fame. “She was always embarrassed by success,” he says. “It was almost like she had to overcome that feeling of embarrassment to be a winner.”

Cotterell has had his own trials and tribulations.

In the early 2000s, he was struck down by autoimmune disease as years of lack of sleep, pre-dawn starts, chlorine fumes and travel took their toll. “I’d been living on three to four hours’ sleep a night, and eight or 10 cups of coffee a day, for 20 or 30 years, and it finally got to me,” he says.

Cotterell also copped flak two years ago when he disbanded his famous Miami squad to coach Chinese swimmers in the lead-up to the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo. His star charge, Sun Yang – the first swimmer to win Olympic gold in the 200m, 400m and 1500m freestyle – was accused by Australian swimmers of being a drug cheat after taking a newly-banned substance for heart palpitations. He could have claimed a medical exemption, but chose not to.

Cotterell says some Australian swimmers have also been guilty of doping violations and should not be throwing stones from the proverbial glass houses.

“It was three years ago, but people have never stopped getting into Sun Yang about it unfortunately,” he says. “He’s a sensitive guy and he’s been very upset by the suggestion that he’s not clean. People don’t know it, but he and all the Chinese winners drive themselves crazy to stay clean.”

Cotterell says coaching the Chinese allows him to prepare the swimmers for major meets over several months before having an extended period off, giving him more time to spend with his partner Bronwyn, a physical education teacher, and go surfing.

“It’s a much better life balance,” he says.

Cotterell says he would have loved to have been on the pool deck for his home city’s Commonwealth Games, but it wasn’t to be, and he will probably watch the swimming on TV.

“There’s enough talent there for Australia to do really well,” he says.

While he never had the time to have a family of his own, Cotterell says his Miami swimming ‘family’ will always have a special place in his heart. “I’ve coached so many kids from the age of eight or nine up until they were in their 20s, and I’ve coached the kids of some those kids,” he says. “It was hard to walk away from that, but the time had come. It was a huge part of my life and I’ll always treasure the memories.”