BUSINESS & EDUCATION

AN UNCOMMON COMMODITY

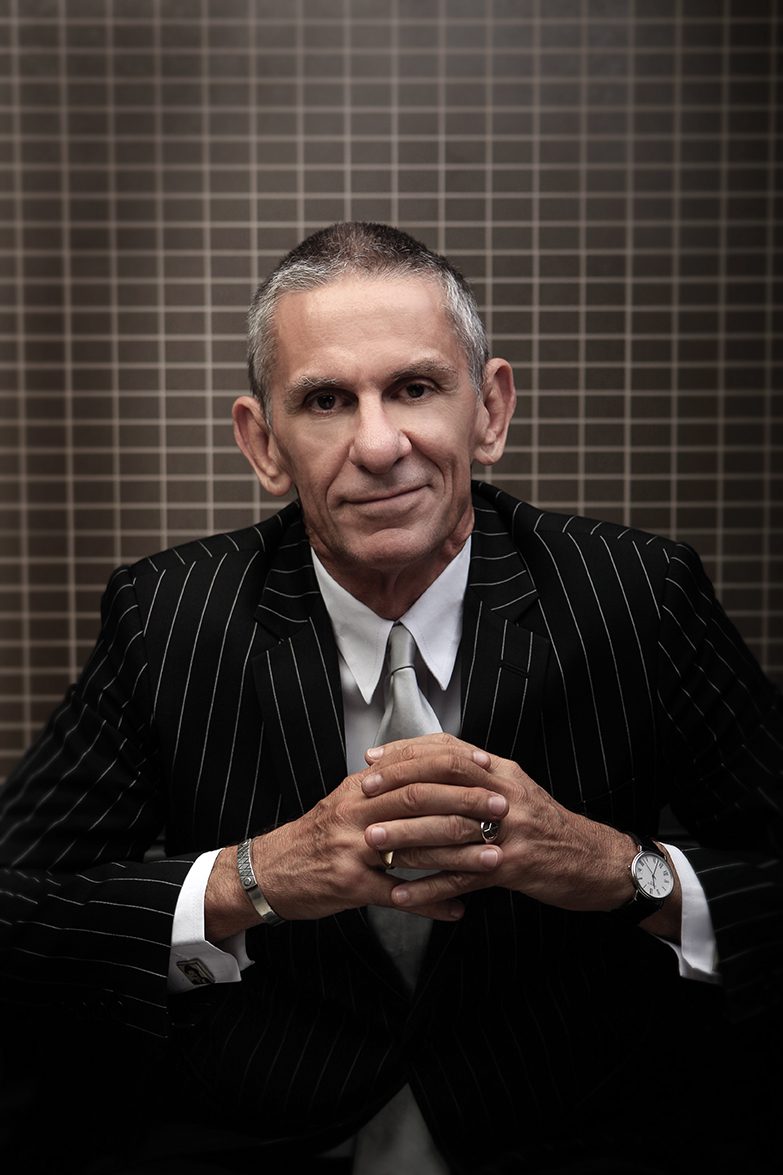

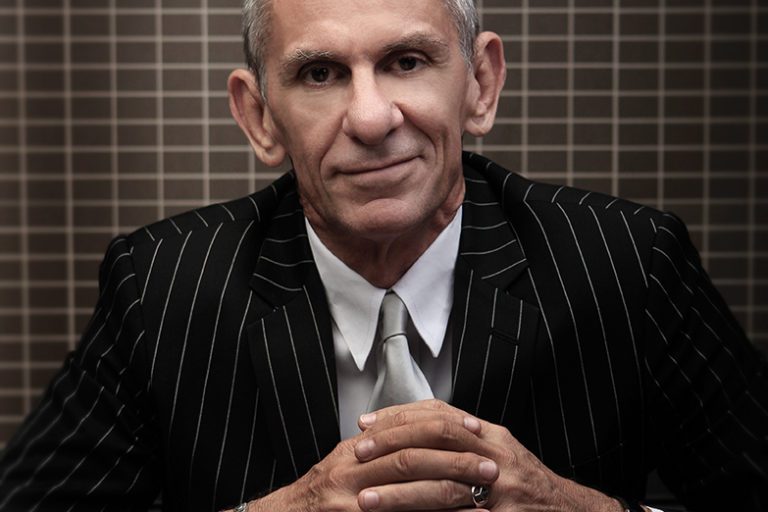

WORDS: PHOTOGRAPHY

Without doubt, self-preservation is the most powerful and compelling of all human instincts. The will to survive – physically, emotionally, financially – is acute and compelling, inextricably ingrained in our human condition.

In his 2007 book Courage: Eight Portraits, former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown used the stories of eight outstanding figures of the 20th century to construct an intimate study of the concept of personal courage. Each of his subjects had one feature in common – their willingness to ignore their own well being in favour of a perceived greater good. It was not fool-hardy, risk-taking bravado that Brown focused on, but what he referred to as “sacrifice and determination for a higher purpose; the courage that endures and prevails, and eventually dignifies all humanity.”

I recently acted for a young man summoned to appear at a secret hearing, conducted behind closed doors, as part of a criminal investigation by a standing commission of inquiry. Euphemistically referred to as “Star Chamber hearings,” over the past several decades such secret inquisitions have become an essential and commonplace element of the Australian legal landscape, conducted by investigative bodies like the Australian Criminal Investigation Commission, the Queensland Crime and Corruption Commission, and a host of other inquiry commissions around the country, to gather criminal intelligence. The big feature that essentially distinguishes the investigative powers of such commissions from those of traditional police forces is their power to compel their targets to answer their questions. Like the citizens of all countries that inherited the British system of justice, Australians enjoy a Common Law right to silence. That means no one can be forced into answering questions, or coerced into saying anything they think may incriminate them. It’s a fundamental right considered by many so elementary and essential to liberty that countries like America have enshrined it constitutionally, meaning no law can be passed to erode or remove it. But in Australia the right to silence can be removed by legislation, and that’s what invariably has been done in the case of our commissions of inquiry.

So my client was given no choice. He had to answer whatever questions were asked. He was told the hearing was secret, he had nothing to fear, nothing he said would ever be published, and no one would know what he said. His answers could never be used against him, unless what he said was untrue.

And therein lay the rub – if anything he said was deemed by the commission to be false, he could be charged with perjury.

But he had no problem with that. He had nothing to hide. There was no allegation against him. Someone had claimed that his boss, a political figure, had seriously blotted his copybook in the presence and hearing of my client, so the commission was looking for evidence to shore up the case.

The only problem was my client claimed he knew nothing of what was being alleged. If his boss did anything wrong, he knew nothing about it.

And when he testified at the inquiry that’s exactly what he told the commission. But that didn’t cut it. The message was clear from the commissioner. We’re not interested in you. We’re not suggesting you’ve done anything wrong. But we know what happened, and we believe you were present. We know the truth, and we want you to confirm it was so. If you don’t confirm what we believe to be true, we’ll conclude that you’ve lied, and we’ll charge you with perjury.

My client had a lot to consider. He wasn’t a criminal. He was just an ordinary, everyday Joe with three kids and a mortgage, pulling a wage and doing his job. Yesterday his biggest gut-ache was making the train on time; tomorrow he was facing the prospect of selling his house to pay lawyers who may or may not succeed in keeping his butt out to gaol.

There were a lot of hard questions, but one easy answer: say what the commissioner wanted to hear.

My mind wandered back to the infamous case of The Crown versus Falzon. Way back in 1989 – another time, another world – in the wake of the Fitzgerald corruption inquiry, I was retained by Michael Paul Falzon, a bushie biker from rural Mackay, charged with cannabis production. The main witness against him was an old drifter Fitzgerald investigators were convinced knew Falzon had been harvesting hooch with a local detective. So they put the frighteners right through him. Two lawyers attached to the Inquiry interviewed him with vigour, on tape, threatening to bury him “lower than shark-shit” if he didn’t admit what they knew to be true. At first the old man denied it, but soon his courage dissolved, and eventually he became a crown witness.

Naturally I subpoenaed the tapes, which disclosed the extent of the investigators’ threats, and the learned trial judge, the Honourable Justice de Jersey (who would later become the Chief Justice and eventually the Governor of Queensland) summarily excluded the witness’s evidence, ruling it was improperly obtained. The legal profession was agog at the investigators’ outlandish behaviour, and one defrocked police detective even quipped to me privately “I lent on plenty of witnesses to get what I wanted, but I was never silly enough to do it on tape!”

Perversely, the very behaviour the law so roundly decried in that case, soon became enshrined as standard procedure by commissions of inquiry established in the wake of Fitzgerald. Nowadays the practice of threatening witnesses with dire consequences if they don’t fall into line with what is proposed as ‘the truth’ is everyday practice.

My client had consistently assured me it just wasn’t true. If his boss did something wrong, he wasn’t aware. But when push came to shove, was he willing to gamble his future, and that of his family, ona matter of principle? Courage is a lamentably uncommon commodity. My client agreed that he’d seen it and heard it. He signed up the statement, and they let him go home.