CRIME

KILLER NEXT DOOR

WORDS: Denise Cullen PHOTOGRAPHY Supplied by the Australian Police Journal

An Ipswich (Queensland) missing person’s report turned murder investigation proves a little forensic knowledge can be a dangerous thing.

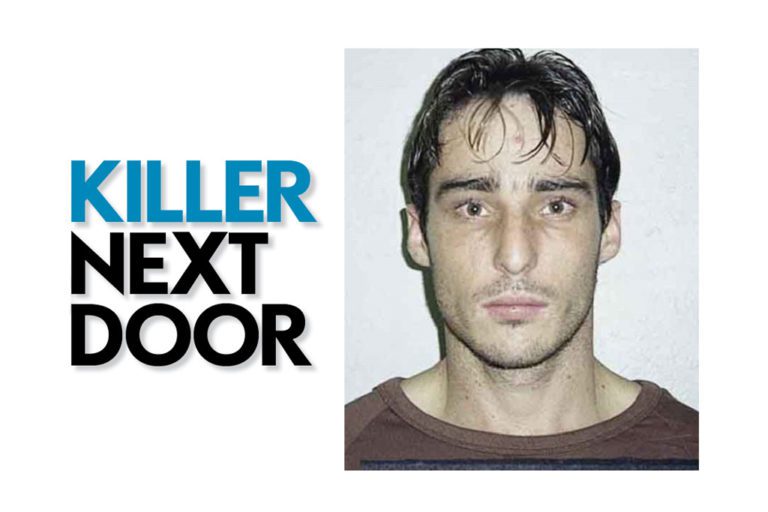

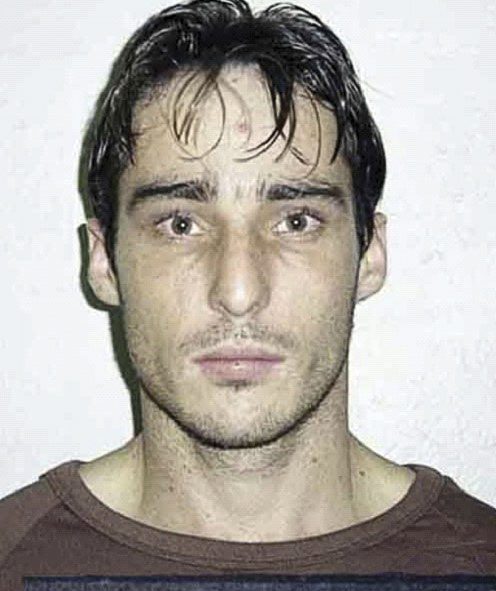

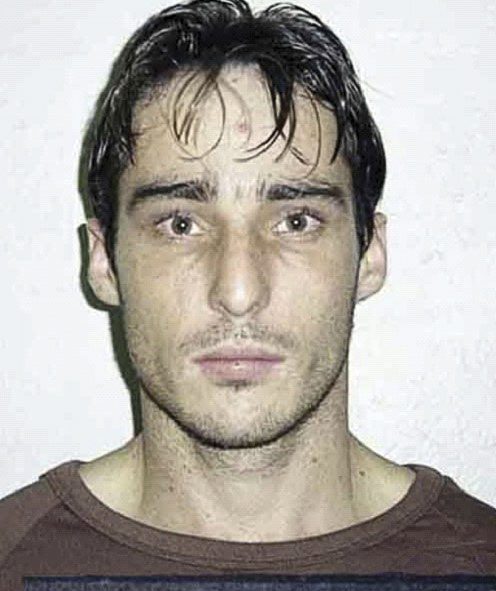

Convicted Murderer – Paul Anthony Vaughan

JUNE 1999

Twilight was turning to darkness when 17-year-old Nicole* stepped off the bus and started walking towards her home in Brisbane. It was the same route she took every day. She didn’t notice the stranger watching her—hadn’t seen him on the other days either—so she was blindsided when she felt his hot breath on her neck as he seized her and forced her into the boot of his car. He drove and drove. She gathered her wits. Fought back. Screamed. Kicked out the tail light of his car. Then he stopped, opened the boot, said something – she doesn’t recall what. She noticed a thick roll of packaging tape in his hand.

“Are you going to tie me up with that?” she said. “Please don’t.”

There was something about her manner which softened his resolve. He invited her to sit in the front seat, placing the packaging tape on the seat between them. He started to drive again. Nicole spotted a knife in the centre console.

“Are you going to kill me?”

“Nope.”

He grabbed the knife and threw it out of the car window. “I’m not gonna kill you.”

But he indicated, in crude terms, that he still intended to tie her up and rape her. Nicole cast about for a means of escape. A diversion. She offered the man some cannabis. The gesture seemed to calm him down. After driving still further, he released her, without causing her further harm. When police located her abductor, he pleaded guilty to a charge of having assaulted Nicole with intent to rape her—having detained her against her will with intent to carnally know her. He was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment. Though prison authorities opposed his early release to parole in 2002, he was back out in the community in less than three years.

31 AUGUST 2004

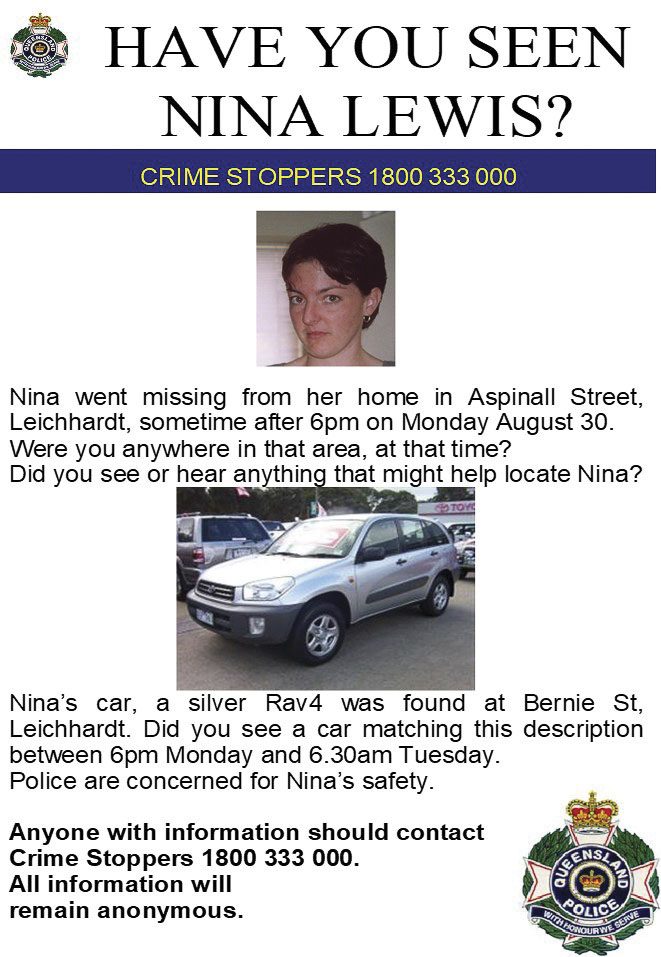

It wasn’t like Nina Lewis not to show up for work. Unable to reach her by phone that Tuesday, Nina’s boss at the Goodna Cash Converters and two workmates went around to her home in the Ipswich suburb of Leichhardt. There, they found her car missing, her front door unlocked, and the house in disarray. Telephone logs show that Nina’s concerned colleagues called police at 2.48 pm.

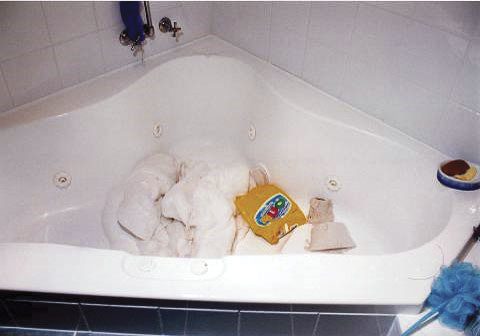

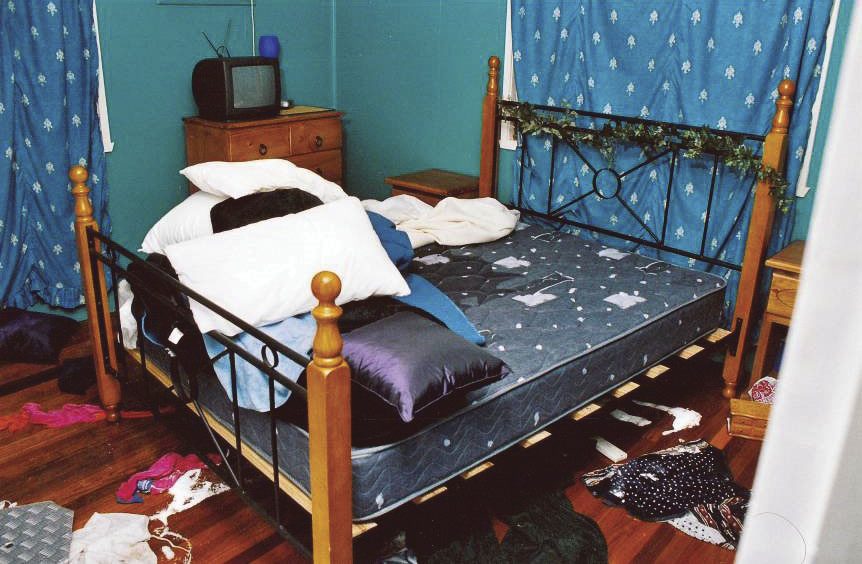

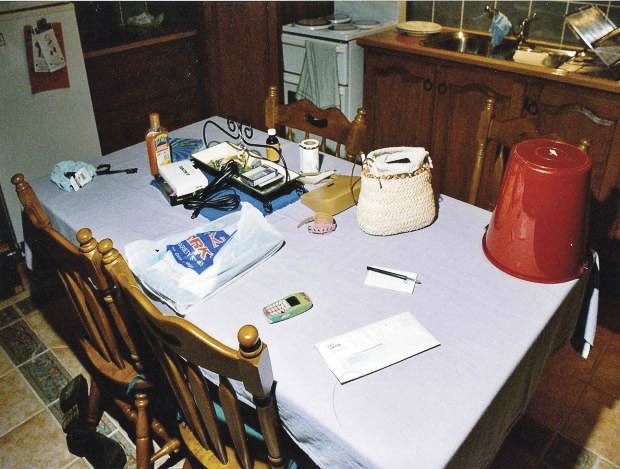

The officers who came to take the missing person’s report shared Nina’s colleagues’ sense of dread. Toilet rolls, an opened packet of washing powder and a doona had been used to block up the overflowing spa bath. Hot water flooded the house. Condensation clung to the ceiling. Undissolved laundry powder was scattered on the tiled and wooden floors. The double bed had been stripped of linen, and pillows and cushions haphazardly piled atop the mattress. Though the house had been ransacked, Lewis’s mobile phone, wallet and handbag, sat untouched on the kitchen table. Responding officers noted cash lying on the floor, in plain sight. Whatever this bizarre scene was about, it wasn’t money.

But something of a story was starting to take shape. The scattered laundry powder and flooded floors suggested that whoever had done this had desperately wanted to wash away the physical evidence. This, in turn, revealed an understanding of the importance of forensic evidence to police investigations. Worldwide, investigators report that crime scenes increasingly bear the tell-tale marks of their architects’ forensic awareness. Gloves are worn to avoid leaving fingerprints. DNA-destroying bleach is used to clean up blood. Bodies are dumped to delay their discovery. Television crime dramas are sometimes blamed for increasing levels of forensic awareness – the so-called ‘CSI effect’. Some have even called for shows such as Waking the Dead and Silent Witness to stop giving the secrets of forensic science away. However, another explanation is that the forensically aware offender has had previous brushes with the law. The British criminal profiler David Canter claimed that offenders who are able to hide their tracks have probably been in the criminal justice system before. They’ve had the opportunity to learn from their past mistakes.

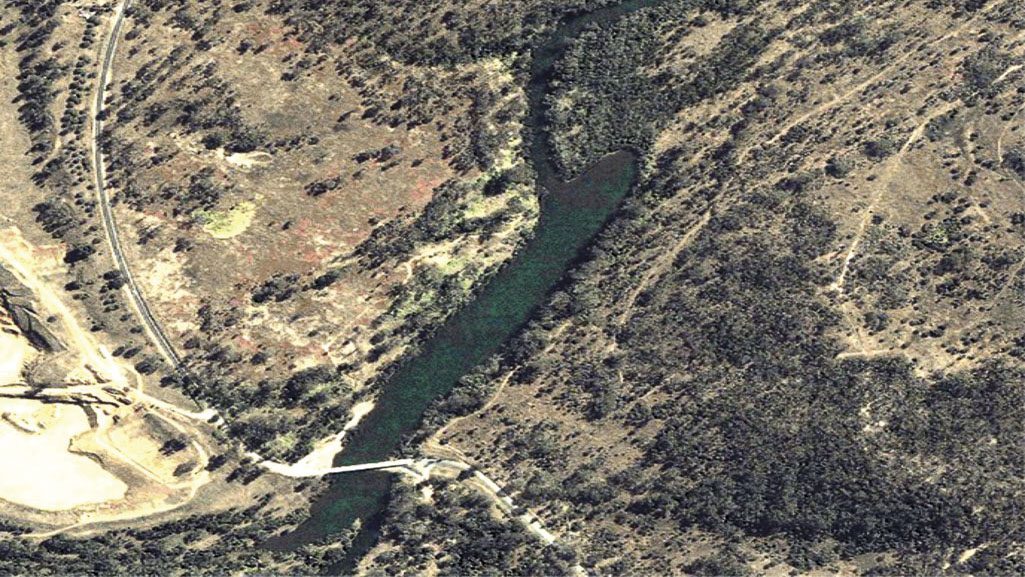

Just over an hour after the first call to police was made, searchers located Nina’s missing silver Toyota RAV4 in bushland at Wulkuraka, behind a Steggles factory, about a kilometre from her home. The inside of the vehicle had been stuffed with hay and pillowcases and towels from Nina’s house. It also contained a pair of men’s running shoes, and number plates which had been ripped off the vehicle, folded up and stuffed under the front seat. Scorch marks suggested that whoever had assembled this bizarre tableau had then started a fire, presumably in an attempt to send the car and its contents up in smoke. But the person responsible had then rolled up the car’s windows and shut the doors, starving the fire of oxygen. Instead of destroying evidence, the would-be arsonist had unintentionally preserved it.

Detective Senior Sergeant Tom Armitt, now working within the Fortitude Valley Criminal Investigation Branch (CIB), has been involved in more than 60 murder investigations, many of them high profile, including the murder of Dulcie Birt (1) and Eunji Ban (2). But, at that time, he was a plainclothes constable with Ipswich CIB. He’d already worked from 8 am to 4 pm but received a call from his boss at around 7.30 pm. “He told me to come back to work immediately, as there was a missing person’s job, and he had a strong sense that it might be a murder,” Armitt said.

A major incident room was established. Police conducted neighbourhood doorknocks, scoured bushland, took statements, and made media appeals. Nina’s house and the site of her abandoned car were cordoned off as crime scenes to allow scientific examiners to do their work. Bank and telephone records were seized. One of Armitt’s first tasks was to take statements from Nina’s friends, family members, neighbours and colleagues, in order to complete a thorough victimology. “We were looking for any angle to start working on why she went missing, and we needed to know her habits, her friends and associates; anything to get us started,” Armitt said.

Piece by piece, a fuller picture of the missing Nina Lewis came into focus. A long-term relationship had broken down six months earlier and, in its wake, Nina had become depressed. However, she had since emerged from the gloom and was getting rid of the reminders of that relationship. On the Sunday, she’d gifted her ex-partner’s gym set to a colleague, in whom she had some romantic interest. After loading the equipment into his car, the pair had shared a beer, and then a kiss. On the Monday, she’d gone into Goodna Cash Converters on her day off. She borrowed a large ball-peen hammer, so she could knock down the bolts in the concrete floor of her garage. The bolts had previously been used to secure the gym set but were now a trip hazard. Nina and her boss had lunch before she headed home at about 2.30 pm – her last known sighting. She rang her mother at about 6.00 pm that night – her last known conversation.

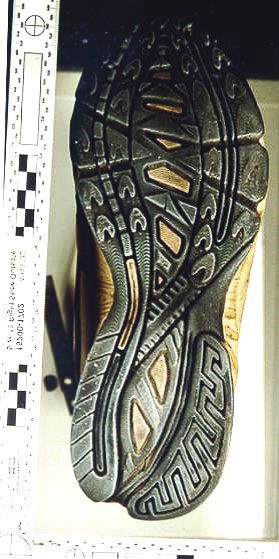

Searches of Nina’s house, car and their respective surrounds continued. The ball-peen hammer was nowhere to be found, nor was there any blood evidence or fingerprints. But a distinctive shoeprint was located in the pile of undissolved washing powder on the kitchen floor. The tread and wear patterns were a perfect match for the shoes found in Nina’s car, meaning the person who’d dumped and then tried to incinerate them had stomped his way through her house. For investigators, this isolated clue was a stroke of luck. Yet so many unknowns remained. How had this shadowy figure been able to access Nina’s house without causing any damage? Was he known to her? Why had he driven her car back towards her house? Did he live nearby?

Police resources were stretched to their limit because of two other major murder investigations taking place at the same time. Bravo-Settler, the investigation into the triple murder of Neelma, Kunal and Sidhi Singh in April 2003, would continue for another five-and-a-half years before Neelma’s ex-boyfriend Massimo “Max” Sica was charged (3). In eerie parallels to the Lewis case, the Singh siblings were found dead in an overflowing hot spa at their parents’ home, and the killer had used bleach and other materials to clean the murder scene but left behind a sock print. Bravo-Vista, instituted following the disappearance of Daniel Morcombe from a bus stop on the Sunshine Coast just before Christmas in 2003, was also consuming significant amounts of investigators’ time and attention. It would be another eight years before Brett Cowan was charged with the teenager’s murder (4).

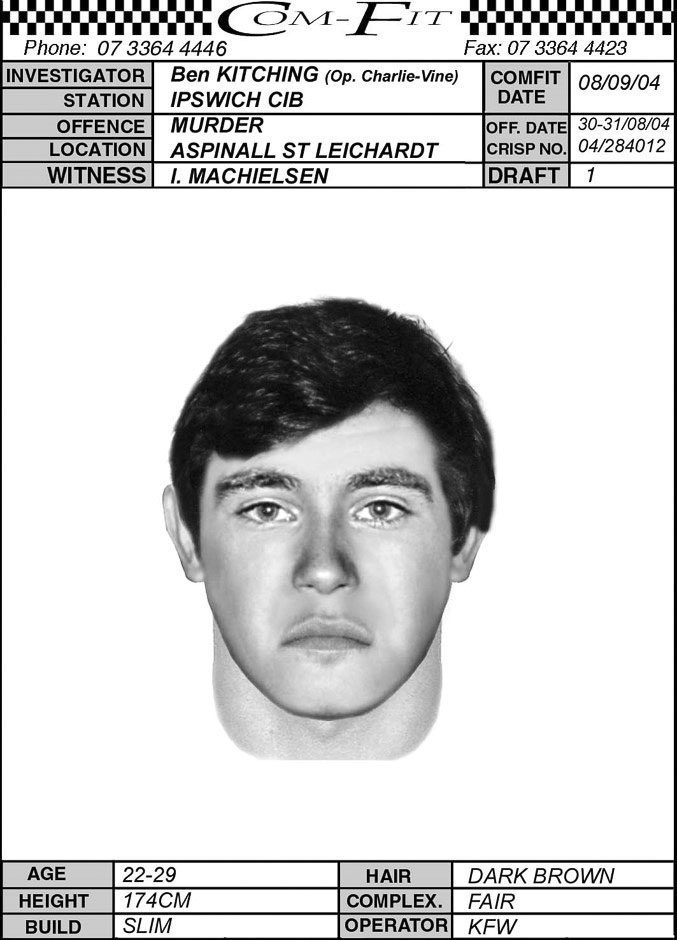

As a result of police doorknocks, and the distribution of fliers, many residents reported seeing Nina’s car on the evening of her disappearance. The timing of these sightings differed, but most mentioned a dark-haired man, driving aimlessly around the neighbourhood and nearby streets. One witness, who was out with his children while walking the dog after dusk, provided chilling additional details. The witness thought he’d noticed a girl in the car, and “It looked like she was sleeping”. He sat down with a police artist to complete a computer-generated image (COMFIT) which turned out to be an eerily accurate representation of the man who would ultimately be apprehended. Searches had also identified a new crime scene – a small patch of bushland which yielded a roll of grey duct tape, and a small ‘RAV4 camel’ soft toy. The latter was one of a range of branded accessories released by Toyota Australia in time for Christmas 2003. Witnesses who knew Nina well confirmed it to have come from Nina’s car. However, what happened to her at this lonely spot remained unknown.

4 SEPTEMBER 2004

On Saturday afternoon, a kayaker navigating a bend in the Brisbane River near Ipswich came upon a woman’s body in the water. The lower half of her body was unclothed, she’d been blindfolded and gagged, and her wrists and ankles were trussed with grey and black duct tape. The grisly discovery was made several kilometres downstream from the Kholo Creek Bridge, near to where the body of Allison Baden-Clay would be found, by another kayaker, eight years later (5). Police efforts were now officially a murder investigation, code-named Operation Charlie-Vine. The body was transported to the John Tonge Centre at Oxley for forensic analysis. Meanwhile, police divers and SES volunteers combed the river and its banks for days in search of further evidence. By the investigation’s end, dozens of people would have been interviewed and hundreds of pieces of information examined by a team of 20 detectives.

Nina was identified from dental records. The autopsy revealed that, with no water in her lungs, and large skull fractures, she had not drowned. Rather, Nina had died from massive head injuries. She was believed to have been bludgeoned to death with the missing ball-peen hammer, subsequently located by police divers in the water just off the river bank. Sergeant Andrew Rowan from the Queensland Police Service’s scientific section also recovered other items – towels from Nina’s house, and the pants she was wearing on the day of her disappearance. These pants also had duct tape attached to them. “(Rowan) did the tape mechanical fitting and the removal of the tape from Nina’s body and was instrumental in the preserving of the vital evidence,” Armitt said. “He was able to confirm that the section of tape that was attached to the pants fitted in a sequence of application to her body – the black tape first, followed by the silver.” Police hypothesised that Nina’s killer had violently “blitzed” her in a surprise attack as she answered her door. After disabling her, the perpetrator had fashioned a sling from her doona cover in order to move her to the car. She was kept captive for several hours before being killed.

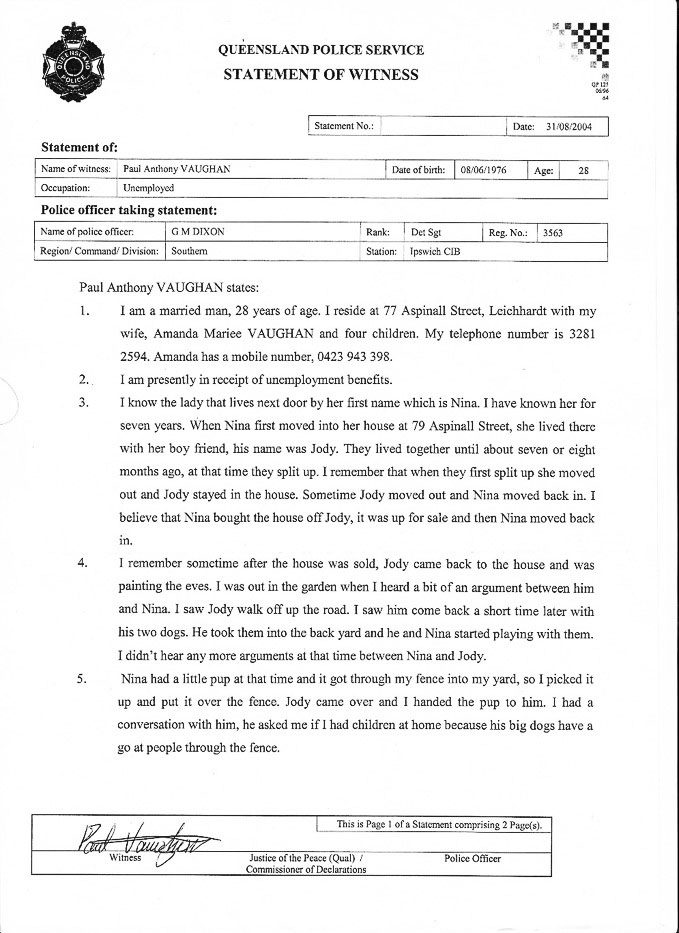

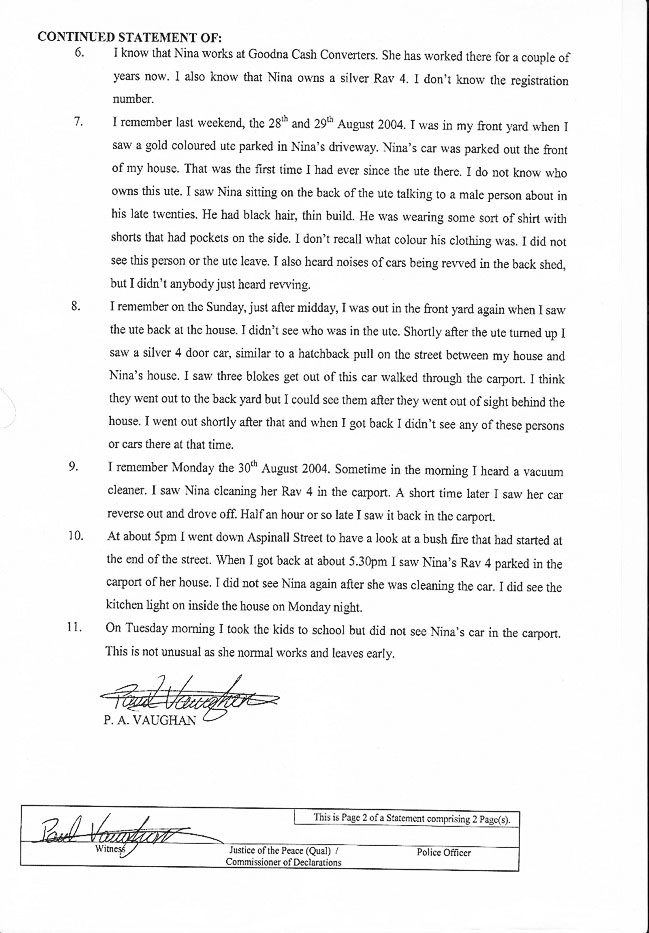

Suspicion was beginning to settle on Nina’s neighbour, Paul Anthony Vaughan. Aged 28 years, Vaughan lived next door with his wife and four children. He’d already spoken to police and provided an innocuous statement in the early days of the investigation. On the Sunday, he said, he’d seen a ute parked in Nina’s driveway; she’d been sitting in the back of it talking to a man in his late 20s, black hair, thin build. On the Monday morning, he saw Nina vacuuming her car in the carport. The vehicle was still parked there late that afternoon. “On Tuesday morning, I took the kids to school but did not see Nina’s car in the carport,” he said in his two-page witness statement dated 31 August 2004 (the day Nina was reported missing). “This is not unusual as she normally works and leaves early.”

However, police knew that Vaughan was still on parole for the June 1999 abduction of a teenage girl who had managed to talk him out of raping her with the promise of cannabis. At the time of Nina’s disappearance, Vaughan was five months’ shy of his full-time release date. When police went back to see him the day after his initial statement, he tried to pretend it had slipped his mind. “There is one thing I forgot to tell youse blokes last night. That, um, I’m on parole, and I did – I did two-and-a-half years’ gaol as well.” Police asked for further details. “For something similar – a similar offence, but it was attempted rape [indistinct]. I’m still on parole for it and stuff … I got a five-year sentence [indistinct]. Apparently, I was supposed to have chucked her in the boot of – boot of my car and that, and drive her out and was going to rape her and that, but then I took her home. And then they got me for [deprivation] of liberty and attempt to rape.”

Vaughan was asked to return to the police station where he provided another statement to police. This time he also accounted for his movements in the days prior to, during and after Nina’s disappearance. “He told police that he had been ill the night she disappeared and had gone to the hospital for treatment and later returned home and watched a movie,” Armitt said. “We got enough details so that we could follow up and see if we could verify his version or not. This proved to be very important during our subsequent investigations.”

Police kept a very close eye on Vaughan after that. Aware that he was under surveillance, Vaughan became increasingly rattled and attempted to shift blame towards an associate dubbed “Fat Cat”, telling anyone who’d listen that this man was good for Nina’s rape and murder. “He’s the one that carried hammers around and knives, not me,” he protested. He told his parole officer that “the cops are trying to get me for this”. Each successive version of Vaughan’s story became more elaborate, and his behaviour more erratic. He and his wife spent hours driving around town to avoid the active crime scene next door. Vaughan would stop his car at traffic lights, then abruptly decamp, in an attempt to evade police. The cracks were starting to show, but there was still no physical evidence linking him to the crime.

Back in the laboratory, Sergeants Paul Francis and Paul Peacock went to work on the grey duct tape which had been wrapped around Nina’s ankles. In a world-first method using liquid nitrogen, they set about snap freezing the tape to neutralise its stickiness and separate its layers. They then examined both the sticky and shiny sides of the tape and found a single fingerprint among the layers. However, when they ran the print through the database, there was no match. Frustrated, the fingerprint experts reassessed. Perhaps the print had been lifted from the sticky side but had actually been transferred there from the shiny side – a mirror image. When they flipped the image and ran it through the database a second time, a hit came back immediately. Paul Anthony Vaughan.

It was the break police had been waiting for. Yet Armitt remained cautious. Could the print have been laid down on the tape any other way than by the owner applying the tape to the victim’s ankles? Fingerprint experts confirmed that the print was embedded on the tape well within the sequence of its application. There was no other possible explanation for its existence other than Vaughan applying the tape to Nina’s body himself.

That was the moment Armitt realised, “We’ve got him.” The level of excitement was palpable, and there were a few quiet high fives as people began to prepare for the next phase of the investigation – locating and arresting Vaughan in connection with Nina’s murder. It was Armitt’s job to conduct the interview. It was also the first homicide arrest of his career.

“The importance of the situation was not lost on me,” he explains. “It was very daunting but also humbling.” Though he was surrounded by a solid team, the pressure not to misstep was immense. “My boss reminded me not to blow it up in my mind too much,” Armitt says. “He urged me to see (the case) as an assault in which a person died and to follow lines of inquiry and questioning as I would in any other investigation so that I could keep my head in the job and not get overawed and miss things, or let the situation get to me.”

9 SEPTEMBER 2004

Vaughan was located as he and his wife drove to attend – of all things – a Tupperware party to which they’d been invited. He was arrested and transported to Queensland Police Headquarters in Roma Street for interview. During the three hours and 20 minutes of interviewing which followed, he maintained a position of “total denial”. “Vaughan (was) very, very cunning, so he would just have an answer for everything despite how ridiculous his lies were,” Armitt said. For example, in a story corroborated by his wife, Vaughan claimed he’d been unwell, and had attended Ipswich Hospital on the night of Nina’s disappearance. However, when police told Vaughan that the hospital had no record of his attendance, he switched tack, claiming that he’d become fed up with waiting. “(There were) too many people up the hospital so I’ve turned around, drive (sic) out of the hospital and went up the main street … (and) drive straight home,” he said.

But, police pointed out, they’d already checked his version and surveillance footage showed he’d never been in that waiting room. Vaughan argued that he’d driven past and seen through the glass doors that the waiting room was full. But surveillance footage from the hospital’s extensive CCTV system showed Vaughan’s car had been nowhere near the hospital that night. “So, then he changed (his story) altogether, saying that he went to his private doctor,” Armitt explains. Investigators continued to pick apart Vaughan’s shifting versions of events. “He’d have to readjust every time we would trap him with evidence that he was lying,” Armitt said. “It showed how the investigators’ groundwork in checking out his version and negating it bit by bit and preparing for the interview was so crucial. Also, it was important for us not to leak info to him as to what we knew and keep laying down open questions to him, letting him trap himself and then refuting it with the evidence gathered. Had we not been prepared, it would not have worked so well.”

Next, detectives moved onto the evidence found in Nina’s abandoned car. Vaughan floated a tale in which he was framed by the real murderer, Fat Cat. Yes, Vaughan agreed, the shoes in the car were his, but they’d been stolen from his front porch, just like a shirt had been stolen from the washing line. The tape used to restrain Nina? That, too, had been nicked from his house. In a revealing exchange, Armitt then asked, “Paul, why would there be evidence from yourself on Nina?” Armitt was referring to the fingerprint found on the tape. However, lacking knowledge of this discovery, Vaughan assumed that, by “evidence”, his accuser meant “semen”.

Vaughan later admitted that he and his friends had discussed Nina, and evaluated her as a potential sexual partner. When Vaughan watched her kiss her colleague out the front of her house that day, it was as if a match had been tossed into kindling, the flames of his sexual deviance roaring to life. Most people who entertain rape fantasies never feel compelled to act upon them. But for men like Vaughan, such preoccupation may serve as a prelude to sexual crimes, particularly sexual homicide.

The day of the kiss, he remarked that Nina was “a slut”. This is consistent with research which suggests that rapists share a common set of implicit theories or cognitive distortions. One of the most common is that “women are sex objects”. Polaschek and Gannon (2004) studied sexual offenders’ descriptions of their offence process. The “women as sex objects” implicit theory was amply portrayed by one participant in the study who stated, “I remember thinking, ‘Oh, I’m fucked now. I’m going to prison for a long time, so I may as well get the most sex out of this that I can’.”

Detectives finally asked Vaughan outright if he had killed Nina. He exploded. More anger. More denials. Eventually, Armitt stopped the recording. “We’re charging you with this murder,” he said. “We have more than enough evidence to charge you, and we know you did it, so you telling us the lies and getting caught out just makes it look worse.” Armitt left the room, leaving Vaughan alone.

After several minutes Vaughan began to cry. He requested to speak with police again. He withdrew his earlier statements. He was coming clean, he said. He didn’t kill Nina, but he had been present when Fat Cat did, and he gave a detailed description of events and locations. Vaughan sat in a second interview with the police and said that Fat Cat had broken into Nina’s home, knocked her down, and tied her up and placed her in her own car. Fat Cat tried to have sex with Nina at the site where the camel toy was found, but Nina had kicked out and hurt him, and he wasn’t able to do it. Fat Cat then killed her near the Kholo Creek Bridge.

Vaughan took the police to the riverside where police had earlier located Nina’s pants and towels and demonstrated to the police how Fat Cat had killed Nina with the hammer he’d found in Nina’s car. This was the first time the hammer had ever been mentioned. The murder weapon was a detail police had deliberately not disclosed. As such, Vaughan was showing the police his intimate knowledge of details only known to the killer. The detectives were less than impressed. “He knew then that he was trapped in his lies,” Amitt said, with a shake of his head. “His change of heart in making the semi admissions was calculated to suit his situation in that he could account for him being involved and leaving his prints but not actually doing it.”

But because Vaughan’s latest version was out there, it had to be explored. A crucial part of his narrative was that when he and Fat Cat drove out of the bushland location where the toy camel was located, they were seen by a person driving a white Ford utility who seemed to have paid them particular attention. At that time in the police investigation, no witnesses had come forward to report this sighting. So, police made a public appeal. Barry* then made contact. He stated that he was the man driving the white utility and that he recalled seeing the Silver RAV4 leaving the bushland that night. When police pressed Barry to provide a time frame for these events, he provided more than just a guess. Barry knew he’d left his home immediately after logging off the internet that night. His computer recorded that time as exactly 12.02 am. As he left his house and drove up the street, he saw the RAV4 exit the bush and drive down towards the railway line. Something about it made him think the car had been stolen. But, shrugging his shoulders, Barry had decided to drive on, not sure of what he’d seen. This gave police almost the exact time that the RAV4 had been driven away from bushland.

Continuing on with the police investigation, Fat Cat was interviewed, and his house was searched. He denied killing or raping Nina. He was able to recall and account for his movements in which he shared his home with his elderly grandmother. Both of them were night owls and unemployed. One of Fat Cat’s regular habits was to drive to a highway roadhouse on the Cunningham Highway near North Ipswich to purchase takeaway meals from the hotbox. “He said he liked that service station, as it was open late and catered meals well after other places had shut, which suited his lifestyle,” Armitt said.

The night of Nina’s abduction, Fat Cat had driven to the service station to purchase a meal for himself and his grandmother, which they consumed at home. The location gave police a means by which to verify Fat Cat’s story, and they seized the service station’s CCTV footage. Police determined that Fat Cat had spent 20 minutes at the service station that night, talking to the attendant and waiting for his food to be prepared. Fortunately for Fat Cat, this corresponded to the same stretch of time in which Barry had reported he had seen the silver RAV4 leaving the bushland. “Fat Cat could not have been in that RAV4, nor could he have been involved in the murder as Vaughan stated,” Armitt said. Only Vaughan could have been in that RAV4 because Fat Cat was confirmed to be kilometres away at precisely the same time. “This was probably the luckiest and best-tasting meal of Fat Cat’s life,” he added.

CONVICTED

Vaughan was unrepentant during his first court appearance. Handcuffed as he was escorted out of Ipswich Magistrates Court, he yelled “love youse”, to no-one in particular. For the next two years, the case proceeded through the courts. In police interviews, Vaughan acknowledged that he had changed his modus operandi based on the mistakes he’d made in 1999. The evidence against him, in that case, included shoeprints, fingerprints and fibre analysis. When in Nina’s house, he wore pillowcases over his feet and hands so that he wouldn’t leave prints. He’d only handled the sticky tape with bare hands because it wasn’t manageable any other way. From the earlier abduction, Vaughan had also learnt not to leave behind a live victim. In this respect, Vaughan’s actions were different from other sexual homicides, in which the torture and death of the victim is part of the thrill. Vaughan’s motive for killing was more pragmatic. It was to avoid getting caught.

Convicted Murderer – Paul Anthony Vaughan

But these admissions, and their relationship to previous convictions, were creating all kinds of legal headaches. There was much argument about the admissibility of Vaughan’s prior criminal history, due to his habit during an interview of referring to “when I got done before”. Every single time this legal argument arose, Armitt’s heart was in his mouth, thinking that this could cause the case to collapse.

“To admit evidence of prior offending is not allowed in court as it jeopardises a person’s right to a free trial and the pure examination of just the evidence before the court,” Armitt explained. “The evidence of propensity or similar fact is highly contentious as it may unfairly sway a jury. The reason it was so important in this case was Vaughan’s constant referral himself to his own prior offending in his interview as to why he did or did not do something. So, every time he mentioned this, there was a risk the court could rule it inadmissible which would then strongly reduce our ability to produce evidence of his interviews in the lies and the later ‘confession’ before the court.”

The Queensland Court of Appeal heard the legal arguments presided over at the time by Chief Justice Paul de Jersey. It was ruled that evidence of Vaughan’s prior offending could not be led by the prosecution in the form of the first victim, Armitt noted. However, the admissions and the references made by Vaughan to his prior offending were admissible in that they were direct evidence of what was on his mind and drove his actions during the commission of the offence.

13 NOVEMBER 2006

Finally, having lost his legal fight to exclude his interviews and partial admissions, Vaughan crumpled under the weight of evidence and pleaded guilty to the murder of Nina Lewis. He admitted in his plea that everything he’d claimed that Fat Cat did, he’d done. Vaughan received a life sentence. During sentencing, Justice Margaret White described the murder of Nina Lewis as an “appalling” crime. “Her family are utterly devastated at what you did to her,” she said. Under Queensland legislation, Vaughan will be eligible to apply for parole after serving 15 years of his murder sentence. At the time of writing, he remains in prison.

FOOTNOTES

- Dulcie Birt was reported missing from her home in Riverview, west of Brisbane, in 2009. Four years later, her lover Alwyn John Gwilliams pleaded guilty to her manslaughter.

- Eunji Ban was bashed to death in a park near Brisbane’s CBD in 2013. Alex McEwan is currently serving a life sentence for her murder.

- Max Sica was convicted of the murders of the Singh siblings in July 2012, and sentenced to life imprisonment, with a non-parole period of 35 years.

- Brett Cowan was convicted in 2014 of the murder of Daniel Morcombe and sentenced to life imprisonment life in prison with the possibility of parole after 20 years.

- Gerard-Baden Clay was convicted of his wife’s murder in 2014 and ultimately sentenced to life imprisonment for murder, with a 15-year, non-parole period.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Denise Cullen is a Brisbane-based psychologist, forensic registrar and journalist who writes on crime, psychology and law. Read more of her work at www.denisecullen.com.au Twitter: @CullenDenise

An asterisk * in this story denotes the use of a pseudonym

REFERENCES

Armitt, T. (2018). Operation Charlie-Vine.

Balemba, S., Beauregard, E., & Martineau, M. (2014). Getting away with murder: A thematic approach to solved and unsolved sexual homicides using crime scene factors. Police Practice and Research, 15(3), 221-233.

Baranowski, A. M., Burkhardt, A., Czernik, E., & Hecht, H. (2018). The CSI-education effect: Do potential criminals benefit from forensic TV series? International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 52, 86-97.

Beauregard, E., & Bouchard, M. (2010). Cleaning up your act: Forensic awareness as a detection avoidance strategy. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38, 1160-1166.

Beauregard, E., & Martineau, M. (2014). No body, no crime? The role of forensic awareness in avoiding police detection in cases of sexual homicide. Journal of Criminal Justice, 42, 213-220.

Canter, D. (2003). Mapping murder: Walking in killers’ footsteps. London. Virgin Publications.

Carabellese, F., Maniglio, R., Greco, O., & Catanesi, R. (2011). The role of fantasy in a serial sexual offender. A brief review of the literature and a case report. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 56(1), 256-260.

Doneman, P. (2006, 15 November). Concealment led to arrest. The Courier-Mail. Retrieved from www.couriermail.com.au

Foley, P. (2004, 7 September). Body find leads to murder hunt. The Queensland Times. Retrieved from www.qt.com.au

Foley, P. (2009, 24 January). Investigators find a prime suspect and miracle evidence. The Queensland Times. Retrieved from www.qt.com.au

Greenall, P. V. (2012). Understanding sexual homicide. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 18(3), 338-354.

Greive, C. (2004, 9 September). Hunt finds new clues. The Queensland Times. Retrieved from www.qt.com.au

R v Vaughan; ex parte A-G (Qld) [2006] QCA 216

Maniglio, R. (2012). The role of parent-child bonding, attachment, and interpersonal problems in the development of deviant sexual fantasies in sexual offenders. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 13(2), 83-96.

Polaschek, D., & Gannon, T. A. (2004). The implicit theories of rapists: What convicted offenders tell us. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 16(4), 299-314.

Salfati, G., & Taylor, P. (2006). Differentiating sexual violence: A comparison of sexual homicide and rape. Psychology, Crime & Law, 12(2), 107-125.

Simeoni, B. (2006, 16 November). Life sentence for ‘appalling’ murder. The Queensland Times. Retrieved from www.qt.com.au

Watt, A. (2006, 15 November). Family wants justice. The Courier-Mail. Retrieved from: www.couriermail.com.au

Watt, A. (2006, 14 November). Why was killer released? The Courier-Mail. Retrieved

from: www.couriermail.com.au