FEATURED

Judging the Judges

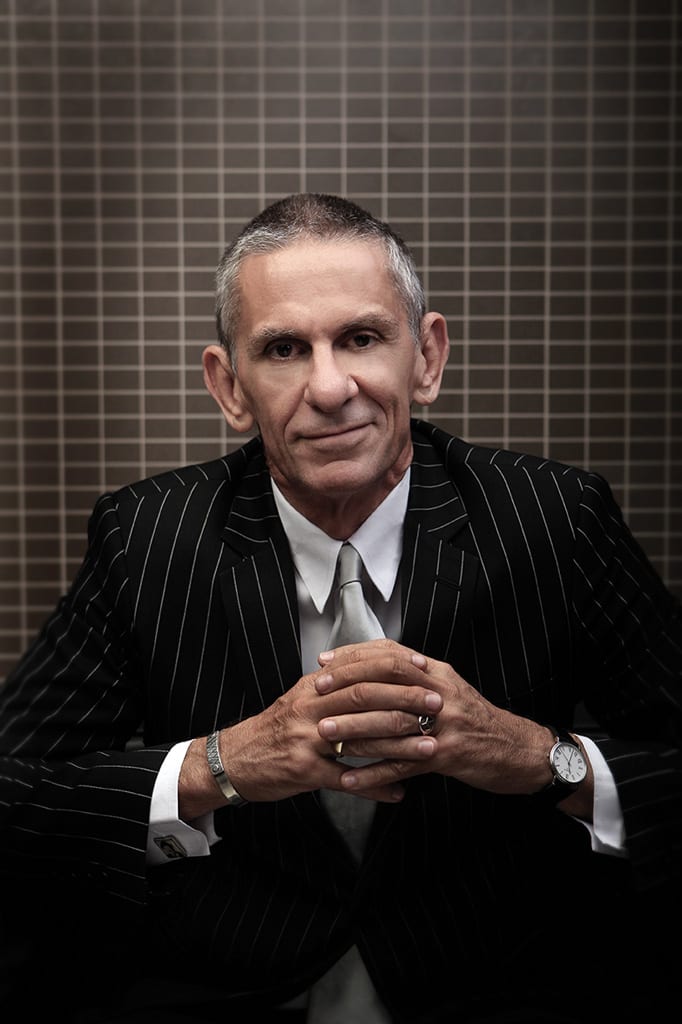

WORDS: Chris Nyst PHOTOGRAPHY Portrait - Brian Usher

I once acted for a wild-eyed zealot charged with possessing and supplying cannabis. He insisted he was entirely innocent, and demanded to defend the charge, not because he didn’t do it, but because the law was an ass. Marijuana use was, he assured me, as old as the pyramids themselves, and hemp was a gift from the gods. Any law prohibiting its use was patently absurd…

My answer was simple. “You could be right. The law could be wrong, wrong, wrong. But it’s still the law. If you want to change it, go run for parliament; but until you do, the law is the law, and you have to obey it.” Unsurprisingly, my client didn’t like my advice, but it was correct.

Whether or not you think marijuana is a medical miracle, if the law says no-go, you can’t have it. No matter how much you want to protest publicly if the parliament says stay off the streets, you stay home. That’s the neat, unswerving, unquestioning approach of all lawyers. But is anything – including the law – really that simple?

In July this year, in the German city of Hamburg, a 93-year-old man was tried in the Children’s Court. Why? Because the crime with which he was charged occurred 76 years ago when he was just a teenaged boy.

In 1944, as a 17-year-old, Bruno Dey was a tower guard at Stutthof, the Nazi SS concentration camp near what was then Danzig, in German-occupied Poland. Set up by the Nazis in 1939 to detain Polish political prisoners, Stutthoff ended up holding 110,000 inmates, of whom an estimated 65,000 died from illness, malnutrition and murder by gas chamber and execution.

Sent to Stutthoff as a Wehrmacht soldier in September 1944, Bruno Dey was found guilty of complicity in the murder of the 5232 victims who perished while he was on guard at the camp.

His lawyer, Stephan Waterkamp, argued that as a 17-year-old, Dey “saw no escape” and could not be expected to defy the SS. But the prosecutor Lars Mahnke told the court “When you are a part of mass murder machinery, it is not enough to just look away.” Judge Anne Meier-Goering agreed. In convicting Dey, she told him, regardless of his orders, he had an overriding duty to “respect human dignity at all costs, even if the cost is your own safety.”

In the wake of World War II, a series of war crimes trials were conducted by US military courts in the occupation zone in the German city of Nuremberg. Amongst them was what became known as the Juristenprozess, or the Judges’ Trial, presided over by US judges in 1947.

By that time, many of the significant figures of the Nazi regime had either been killed or had long since gone missing, but the defendants in the Judges’ Trial were not high-ranking generals or death camp commandants, they were former respected prosecutors and judges of the Special Courts and People’s Courts, where Nazi Germany’s program of racial purification was implemented, by applying the law of the land.

Not surprisingly, the American judges judging the judges found themselves grappling with some very uncomfortable questions concerning the culpability of those who merely administer the law. Was it the role of a judge or a prosecutor to refuse to impose a law they considered inherently unjust? Were they morally culpable for applying the law of the land, if that law was itself reprehensible?

That dilemma was powerfully played out in popular fiction in what became one of the greatest courtroom dramas in cinematic history. Stanley Kramer’s Oscar-winning 1961 film, Judgement at Nuremberg, a fictional dramatisation of the Judges’ Trial – released less than 15 years after the actual events – was a tour-de-force, as controversial as it was highly-acclaimed.

The film featured Spencer Tracy as Judge Dan Haywood; a decent, tolerant man called on to oversee the trial of four German judges – most notably the internationally-respected jurist and legal scholar, Dr Ernst Janning, played by Burt Lancaster – each accused of knowingly sentencing innocent people to death in accordance with Nazi law.

As Janning’s firebrand young lawyer Hans Rolfe (played by Maximilian Schell) brilliantly defends him and his fellow judges, the distinguished judge sits defiantly silent through most of the trial. But eventually, when Rolfe attacks in cross-examination a young woman accused of having a relationship with a Jewish man contrary to Nazi law, Dr Janning rises solemnly to his feet, and dramatically interrupts, in one of the great cinematic moments of the 20th century.

“Herr Rolfe,” he demands, “Are we going to do this again?”

Through outraged objections and uproar in the courtroom, Janning acknowledges his guilt, and all four defendants are sentenced to life in prison.

Later, when the judge visits the sentenced man in his cell, Janning apologetically says of the Final Solution, “I never knew it would come to that.”

“Dr Janning,” Haywood replies, “It came to that the first time you sentenced a man to death you knew to be innocent.”

Of the 16 German jurists and lawyers prosecuted in the 1947 Judges’ Trial, all but four were convicted of war crimes, and crimes against humanity, even though they protested they were just doing their job, dutifully following the law.

The judgement at Nuremberg decided, forever, it’s not quite as simple as that.

Whether you’re a 17-year-old tower guard or the esteemed Chief Judge of the Special Court, there’s still always what’s right and what’s wrong.

Criminal Lawyer Chris Nyst