COVER STORY

In safe hands

WORDS: PHOTOGRAPHY

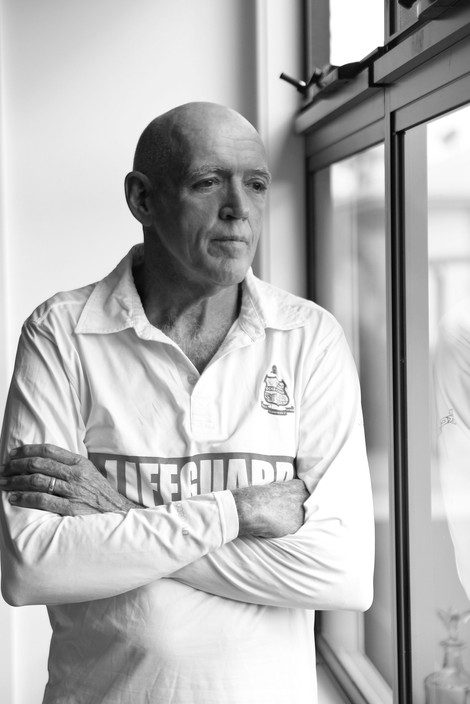

Veteran lifeguard Warren Young talks about serving his city, facing challenges, and hanging up his blue cap after 45 years of keeping watch over the Gold Coast.

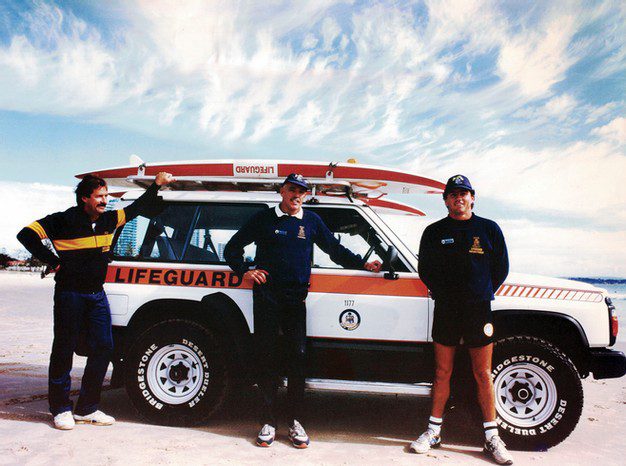

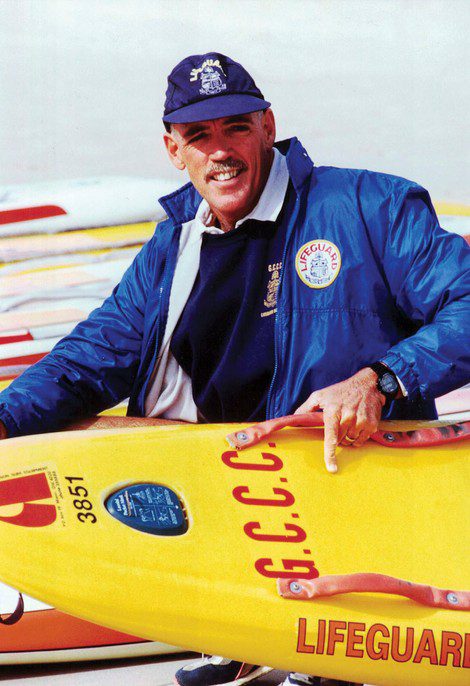

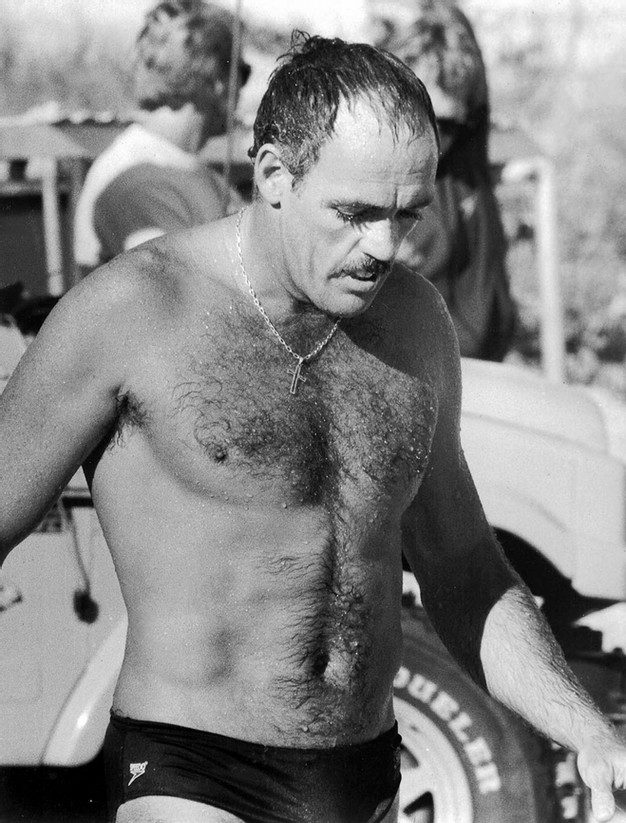

In the tanned and buff ranks of the Gold Coast lifeguard service, Warren Young is the undisputed old salt. But at 69 (he turns 70 in May), our perennially super-fit chief lifeguard still bests some of his much younger colleagues in the service’s gruelling six-monthly fitness tests.

It’s the mark of a man who has devoted most of his life to keeping the Coast’s famous (but often treacherous) 50-odd kilometres of golden beaches as safe as possible. Now, after a remarkable 45 years standing sentinel over the sand, Warren is contemplating the prospect of hanging up his blue lifeguard cap and handing over the keys of his patrol vehicle to one of his loyal lieutenants.

The veteran lifeguard, who’s been dubbed the ‘Silver Fox’, returned recently from extended long service leave to weigh up his future. If he does decide to call it quits, it will be the end of an era for one of the Gold Coast’s true icons.

Warren’s love affair with the Coast and its magnificent beaches began way back in the 1960s when he and his brothers, Blair and Gary, would hitchhike or catch the bus down from their home on Brisbane’s southside to go surfing.

“Mum was a widow and we lived at Acacia Ridge in a [Housing] Commission house,” Warren tells Ocean Road at the dining table of the smart new Koala Park duplex he shares with wife Louise and staffie cross Brandy.

“We were coming down here surfing and I had a mate whose father wanted us to join the [Miami] surf club. I said, ‘Oh, I don’t know; we’re surfers’. But it was the best thing I did.

“You did a two-and-a-half-hour patrol and you could surf all weekend or play touch footy. I really took to it. It was a great environment then. The [surf] clubs did promote leadership. I was appointed club captain in 1972–73 and I really enjoyed it.”

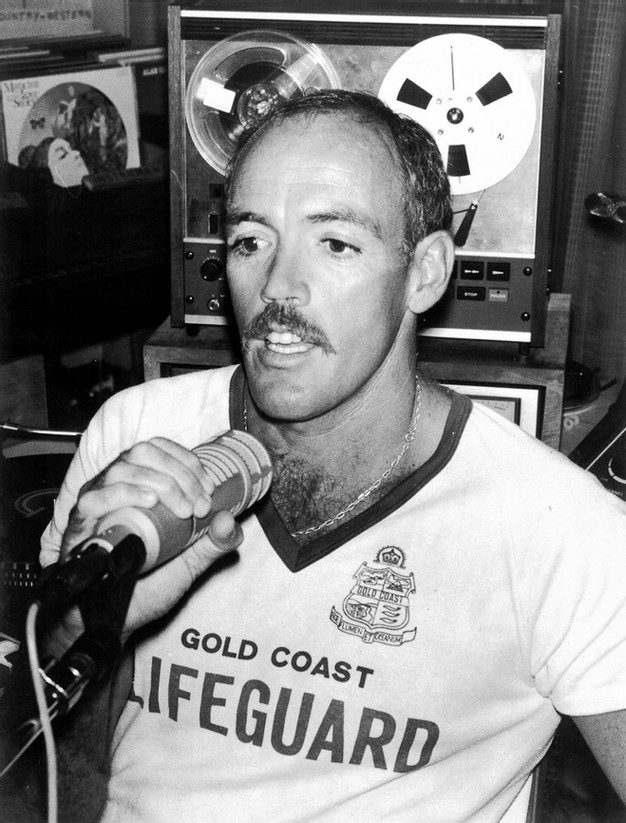

Warren had left school at 15 to work as a telegram boy for Telecom (now Telstra) and later in sales. But in 1973, a job as a beach inspector came up at Burleigh Heads.

“I enjoyed my time at Telecom, but I was working right in the heart of Brisbane and I wanted to be near the ocean,” he says. “The [beach inspector] job came up at Burleigh and I put in for it. Mum was really always supportive and gave us confidence. She let us think we could do anything if we really put our mind to it. I was club captain [at Miami] and I was prepared to do whatever it took.”

With legendary Gold Coast lifesaver and then-lifeguard-boss Marshall Kropp on the stopwatch, Warren successfully completed a swimming time trial at the old ocean baths at Burleigh and duly landed the job. It was the start of what would be an illustrious career helping to preserve not only lives, but also the Coast’s hard-won reputation as a safe family holiday destination.

Unlike today, when two lifeguards usually man the patrol towers and flagged areas, the role of beach inspector back then was a one-man job.

“When you work on your own and you’re responsible for a beach, it really hones your surveillance response skills, because you’re the only one there,” Warren says.

“At first, it’s quite frightening a challenge, but you really read the ocean even better, because you’re looking after people who sometimes don’t know anything about it.”

In April 1975, Kropp — future father-in-law of Warren’s now right-hand man Chris Maynard — decided to vacate the post then known as senior patrol officer.

“All the way up and down the Coast, there were these great big gaps [in patrols] between Broadbeach and Surfers, Surfers and Main Beach, Kurrawa and Miami, and it was getting really dangerous,” Warren recalls.

“There was a lot going on — highrises were going up; there were a few drownings north of Surfers. We didn’t have the staff in those days. So he [Kropp] really felt the pressure and got to the stage where he wanted to do something else in council.

“I’d only been there a year and four or five months, but he advised me to put in for it. He must have seen something in me. Anyway, I got the job. I thought, ‘well, here we go’.”

It was a challenging baptism for Warren, with only about 12 staff to patrol the Coast’s most-popular beaches full-time. Surfers Paradise became known as ‘Death Alley’ after a spate of drownings and near-drownings.

“Highrises were getting built in Surfers,” Warren says, “and people were just going down to the beach in front of their highrise. As you know, conditions along our beaches in certain swell conditions can play havoc. There were some really bad rescues and some drownings, and the Death Alley name was really not good for the Coast.”

The then Surfers Paradise alderman, Eileen Peters (who incidentally was the ‘mother’ of the Gold Coast meter maid service), asked Warren for a solution.

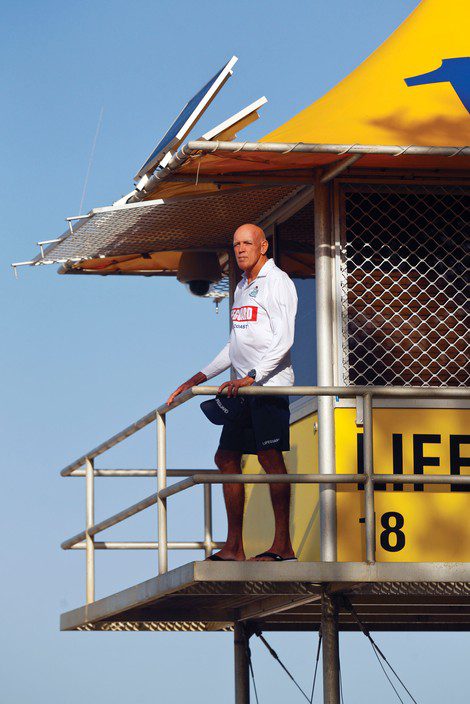

“I said, ‘Well, driving along in a vehicle up and down the beach is only fleeting surveillance. The only guarantee [of spotting swimmers in strife] is constant surveillance from an elevated platform’,” he says.

It led to the installation of the Coast’s iconic yellow patrol towers, starting with one at Staghorn Avenue in Surfers, then Narrowneck, Breaker Street at Main Beach, and eventually right up and down the Coast.

“We had a plan in place and council supported it,” Warren says.

“It helped a lot, because it gave us that interlocking surveillance. That was exciting. I just knew the way our coastline was, there are only a few headlands. So you’ve got this great big expanse [of open beach] and if you can interlock the surveillance and eliminate blind spots, you’re a chance [of saving people]. If there’s no one [lifeguards] there, they drown.”

The first tower did not have a balcony, but these were added after feedback from Warren’s expert team of lifeguards.

“I had guys I trusted, so when you asked for their input, it was just so spot-on,” he says. “One of the guys said not only do you not feel close to the public without a balcony, but you can’t walk out and look north and south — you’re in a box. So after that we got balconies.”

The towers have become a fixture of the Gold Coast cityscape, as emblematic as the famous Surfers Paradise skyline, the theme parks, and the beaches themselves.

“They’re real landmarks — they even won an urban design award,” Warren says proudly. “The towers are always showing up in tourism ads and in paintings at art shows, which just goes to show how iconic they’ve become.”

A lifeguard tower even made an appearance at the opening ceremony for last year’s Commonwealth Games, where Warren and 11 of his comrades had starring roles ushering the athletes into Carrara Stadium.

“It was lovely recognition for the lifeguard service, and we had a lot of fun,” he says.

“Being part of the opening ceremony of the biggest event we’ve ever seen in Queensland was really special.”

But there was also immense pressure on Warren and his team during the Games, with tens of thousands of athletes, officials, and spectators hitting our beaches during the 10-day sporting spectacular — and the eyes of the world watching on.

“We knew the group coming for the Games could range from an unfit person who doesn’t know the ocean to the fittest person who still doesn’t know the ocean,” he says.

“Every beach is accessible 24 hours a day, so it was a real challenge. If you’re relaxed and away from the crowd and no one’s there [watching], they could go [drown] like that.”

Thankfully, Warren and his men and women went above and beyond to ensure beachgoers stayed safe during the mega-event.

As well as the patrol tower innovation, the Gold Coast Lifeguard Service was the first in Australia to get jet skis after Maynard and fellow senior guard Mick Di Betta went to Hawaii one year for a lifeguard challenge and saw how effective the machines were at helping to save stricken swimmers and surfers.

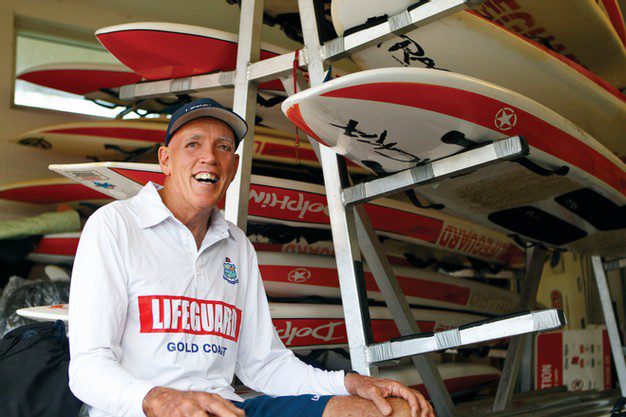

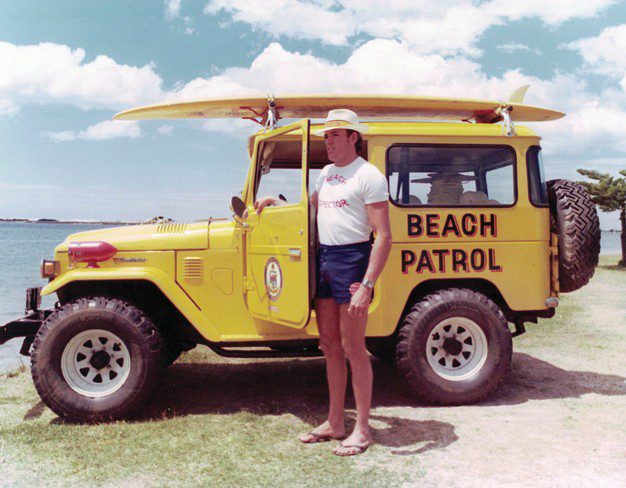

It was a far cry from Warren’s early years when his equipment consisted of a rescue board and a reel, line, and belt on the back of his patrol vehicle.

“Reels were a two- or three-man job, and you just didn’t get them out,” he says of the old-school surf lifesaving device. “If you swim out with one of those and you’ve got the greenhorns pulling you in, you’re going to be underwater most of the time.

“Once I started, I realised that my best friend was the rescue board, without exception. Once you had that flotation, you could actually get people to relax and get them in. And that was so important.

“We also had a siren call system where all the vehicles were fitted with sirens and you could alert other lifeguards of an incident with a push of a button on the radio.”

But Warren says all the technology in the world — including the new-fangled drones being increasingly used in lifesaving — is of little use if a lifeguard or lifesaver doesn’t have their eyes peeled for trouble.

“All those things, the jet skis and everything, are really a backup for the guy on the beach who’s seeing and responding,” he says.

“Whatever happens in this life, if the first responder doesn’t see and react, people die. That skill is just paramount. Once you get good at it, you really start to respond just before someone is in dire trouble.”

While much of his time these days is spent in the office, Warren has been personally involved in countless rescues over the years.

One of the most traumatic was about 20 years ago, when three men were swept out in big seas on the Southport Spit.

“There was no patrol up there then,” he recalls. “We’ve gone up there, and there are waves breaking on the back break. It was an easterly swell, about five foot [1.5 metres]. I’ve gotten there and another lifeguard’s followed me up.

“When we got there, one bloke was already dead. I paddled up to another bloke who was near him. There was a set coming and it was gonna be touch and go. I was trying to get to him before the set hits us.

“I just got to him and said to him, ‘If you let go of this board, you’ll die’. And that’s the last thing I said to him. We’ve got tumbled and all I could feel was this dead weight, which was good, because it meant he hadn’t let go.

“It was so close, because that could have been a double drowning. The ocean doesn’t discriminate. You go out on a soft gutter and all of a sudden you’re on a back bank and you’re in strife.

“The sad ones are when the family’s standing by and you’re trying resuscitation and it’s not going well. It’s not a job where you can pull a curtain over and say, ‘We’ll tell you later’. It’s really difficult at times.”

But there have also been lighter moments, such as the time in 1978 when a photo of an ‘ever-vigilant’ Warren, ordering a woman sunbather cavorting stark naked on crowded Surfers Paradise beach to cover up, was splashed all over the front page of the Gold Coast Bulletin.

It highlighted the many and varied duties of the Gold Coast’s finest: one minute, they can be rescuing a drowning swimmer; the next they can be giving directions to the nearest decent restaurant or helping a frantic parent find their lost child.

“There’s a lot of emotional intelligence involved in being able to talk to people,” Warren says.

“If someone comes up to ask you something, you answer them. ‘There’s a good restaurant here; there’s a movie theatre there. Watch the sun; there are a few bluebottles out there today. Where are you from? Oh, Melbourne. Geez, how good are the Hawks [Hawthorn] going?’

“I used to buy the Melbourne and Sydney papers so I could have a talk about the footy. Once you say to someone, ‘I see so and so’s playing again’, they light up. It’s easy then to talk about the ocean and how they’ve got to be careful.

“I always say to our people, ‘You’re working without a script’. So you’ve got to like people; you’ve got to like talking to them. All the basic things.

“But when you’re talking to them — and it might seem a bit rude — you’ve just got to keep watching the water. And they’ve got to see you watching the water. You’re still talking to them, but your concentration’s got to be on the water. They walk away thinking, ‘oh gee, those guys are on to it’.”

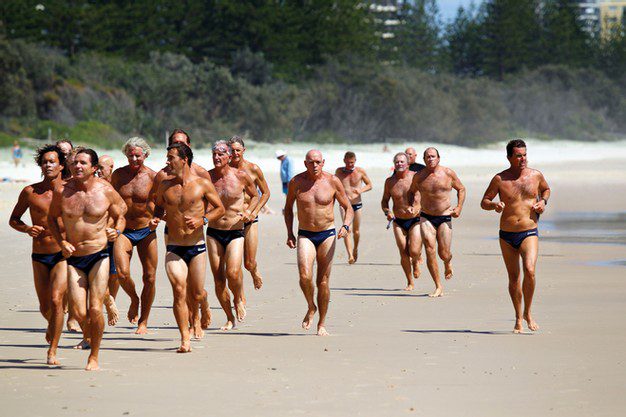

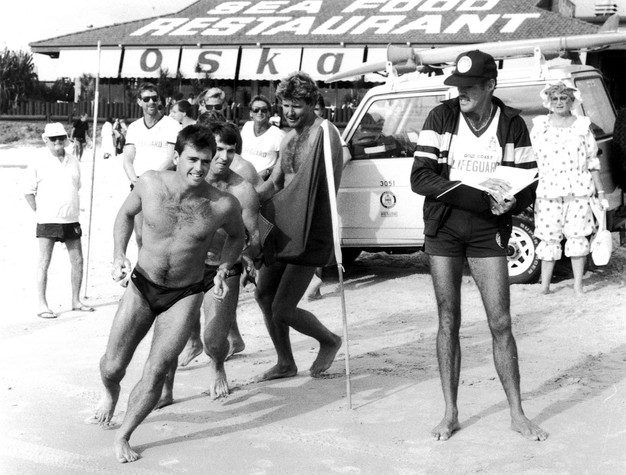

From its humble beginnings, the Gold Coast Lifeguard Service has grown into a $12 million-a-year operation, with 39 permanent staff and 125 casuals who supplement the ranks at peak holiday time, patrolling 39 beaches from Rainbow Bay to The Spit. The guards include top ironmen and ironwomen and even Olympians such as gold medal-winning kayaker Ken Wallace.

“We’ve had some terrific watermen and waterwomen working for us as lifeguards over the years — legends like John Cunningham and Peter Lacey, Olympians such as Ken Wallace and Grant Davies, and guys like [10-time world paddleboard champion and big-wave surfer] Jamie Mitchell,” Warren says.

“You could safely say that we’re one of the most-respected lifeguard services in the world. In Hawaii and the States, we’ve got a very good reputation.

“It’s the same when we go to a lifeguard conference interstate. You know as soon as you speak to those guys and girls that we’re doing the same job, and there’s mutual respect.”

Lifeguarding wasn’t really seen as a viable career in the early days, Warren says, but times have changed.

“The city has grown and the lifeguard service with it,” he says.

“Now we’ve got lifeguards whose children are working with us. Chris Maynard’s daughter and son [top lifesaving competitors Riley and Jackson] and three of my kids (Luke, now 40; Daniel, 38; and Jessica, 36] worked as lifeguards. It’s wonderful to see.’ (Warren and Louise also have another son, Tim, 31.)

Warren says one of the keys to the success of the lifeguard service, which performs between 1200 and 1600 rescues a year, has been the unwavering support of the council (City of Gold Coast).

“We’ve had a lot of support from council — they’ve always been very aware of the importance of beach safety,” he says.

“You only know how important it is when there’s a tragedy, unfortunately. It’s horrific headlines. Death Alley — imagine that headline today? I think this city prides itself on doing things properly.”

Warren introduced the biannual lifeguard fitness test in 1978 and still leads by example, completing the courses every year with his colleagues. One test involves a 750m swim, 1600m run, and 750m rescue board paddle, which needs to be completed in under 26 minutes, while the other is an M-shaped course requiring lifeguards to punch through the break three times.

“The tests involve all the disciplines we use and are both very hard cardio-wise,” he says.

“It’s a job where you’ve got to be fit all the time, and it’s great the way the staff are always prepared for the tests. They and our new recruits know that this is what you’ve got to do to be a Gold Coast lifeguard. There’s no way out.”

Warren, who still swims about 9km a week, admits the test is becoming tougher every year.

“It gets harder — as you get older, you can be fit for your age, but not for any age,” he says.

When he does eventually hang up his rescue board, Warren will have plenty to keep himself occupied.

As well as being a mad-keen surfer, he’s a voracious reader — “I read the labels on Vegemite jars” — and is also a passionate poet and writer. He and Louise also recently returned from a walking tour of Tasmania, and there’ll be more of that in retirement.

Awarded a Public Service Medal in 1999 for services to beach safety, Warren — and the city he has served — will be able to look back on his career with immense pride.

“Looking after people in the ocean is an enormous responsibility, and 45 years is a long time,” he says.

“Not everyone’s cut out for it — watching people in the water. You’ve got to know when to really, really concentrate, but also when to relax a bit; otherwise, you can get burnt out very quickly. When there’s a swell on and the day ends safely, you can tell that our guys and girls are really pleased. We pride ourselves on prevention.”