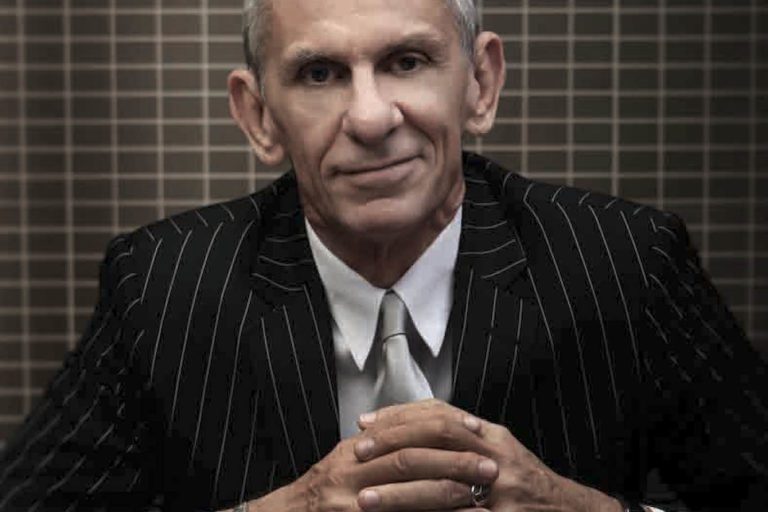

COVER STORY

Criminal Mind

WORDS: PHOTOGRAPHY

With a criminal law career which has spanned three decades and ranged from cops to crooks, Chris Nyst has plenty of stories. Ocean Road visited his Southport offices on the Coast to learn more about his family roots, colourful clients, his novels and films, and TV scripts that are in the pipeline.

I know where all the bodies are buried,” Chris Nyst says, with a wry smile on a face filled with character, tongue planted firmly in cheek.

Or is it?

After a criminal law career spanning more than three decades, Nyst knows some dark secrets he will probably take with him to the grave (unless, perhaps, they happen to bob up cleverly disguised as fiction in one of his novels or films).

“I get told a lot of secrets,” he says, matter-of-factly rather than mysteriously.

Ocean Road is chatting to Nyst in the boardroom of his eponymous Gold Coast law firm, Nyst Legal, from where he has represented high-profile clients including the likes of Pauline Hanson, ‘Postcard Bandit’ Brenden Abbott, arch-conman Peter Foster, tennis bad boy Bernard Tomic, NRL star Greg Bird and the notorious Lacey brothers.

A narrow set of stairs in Southport’s lower Nerang St leads up to his chrome and glass-adorned offices, which resemble a modern art gallery more than a stuffy law firm. In fact, it has doubled as a gallery, thanks to a collaboration with prominent Gold Coast art dealer Lorraine Pilgrim.

Black and white photos of icons including Muhammad Ali, JFK and Martin Luther King hang on the walls and a copy of German-Australian erotic photographer Helmut Newton’s famous coffee table tome, Sumo – with a full-frontal nude of 1980s Playboy model Henrietta Allais on the cover – takes pride of place in the waiting room.

In the hallway, through a partially-opened sliding glass door, you catch a glimpse of a colourful portrait of Nyst, painted by none other than the Postcard Bandit himself. The lawyer sat for the painting in the Arthur Gorrie Correctional Centre.

Today, Nyst is dressed in a sharp brown suit – a departure from his trademark pin-stripes but, like his office, nonetheless fashionable.

He is in his early 60s but is lean and fit-looking, with a physique honed by a love of surfing and boxing. Stylish black specs perch on his nose, which looks like it might have copped a few whacks in his early years as a self-confessed ‘ratbag’.

He was born in Blackall, in south-west Queensland, in 1953 to Edmond and Teresa Nyst, the youngest of three boys (brothers Phillip and Malcolm both are doctors).

The son of former Dutch consul in Marseille, who smuggled Jews into farmhouses around Provence to hide them from the maruading Nazis, Eddie Nyst was, by all accounts, one colourful character. He and his brothers were also forced to flee Hitler’s advances and he fought for the French Resistance when he was just 17.

Eddie later fought for the Dutch Army and alongside the Australians against the Japanese in Borneo.

After the war, he set himself up as a kind of early version of Steve Irwin, spending three-and-a-half years as a field zoologist trapping Australian wildlife including kangaroos, wombats, snakes, possums and galahs for the Rotterdam Zoo.

Eddie became a Brisbane builder but was also something of a renaissance man, whose passions included painting, cinema and listening to orators in the City Domain.

“The old man would take us to The Domain to listen to the guys get up on their soap boxes talk about politics or whatever,” Nyst recalls. “He was a real admirer of the great orators of the day.”

Those orators included Dan Casey, a renowned criminal barrister of the time, and Eddie would also take his sons to the Brisbane Law Courts to see Casey and the state’s other top legal eagles in full flight.

Nyst was inspired by Casey but more so by the films his parents would take him and his brothers to see on a Friday and Saturday night.

“It was the 1950s and 60s and we didn’t have a TV in the early days, we went to the pictures instead,” he says. “I was a bit of a movie buff and decided as a young bloke that I wanted to become an actor. My father was smart enough to convince me that you couldn’t make any money out of acting, and the closest thing to being an actor was to be a lawyer.

“Perry Mason [the fictional American criminal defence lawyer] was big on TV at the time so that probably helped make up my mind to study law.”

Nyst completed his law degree at the University of Queensland alongside none other than his father Eddie, who after retiring from building went on to become a barrister of the Supreme Court of Queensland and High Court of Australia.

“I was a bit of a ratbag back then but he was deadly serious,” Nyst Jr remembered in a 2008 interview.

Nyst did his articled clerkship at the venerable firm of Power & Power in Brisbane’s Edward St.

“It was a very traditional old firm was run by a family of lawyers including Fraser Power, his brother David, father Leo and uncle Leonard so we had to refer to them as Mr Fraser, Mr Leo, Mr David and Mr Leonard,” Nyst recalls with a chuckle.

A love of surfing lured Nyst to the Gold Coast to complete his articles before he and wife Julie, whom he had met in Brisbane, headed off on the obligatory surfing odyssey to Europe, via Bali and Sri Lanka. In Bali, the young couple bought 200 pair of board-shorts and entertained ideas of entering the rag trade after selling them for a handsome profit in the French surf town of Biarritz.

“We bought them for about $2 a pair and sold them for like 25 bucks and we talked about flying straight back to Bali and buying some more boardies,” he says.

It never happened and Nyst had to content himself with becoming a celebrity lawyer rather than a surfwear baron.

After more than a year trekking around Europe in a Kombi, surfing Ireland, Portugal and France and partying with some wild Welsh mates, the Nysts returned to Australia. By this time, Julie was pregnant with their first child Carly, now 32, and a lawyer working in London. Sons Brendan, 31, and Johnny, 24, are also lawyers and work alongside Chris at Nyst Legal (Jonny is also a part-time rock star, with his band The Vernons).

Other daughter Annabelle, 26, is a journalist working with Conde Nast in New York. They’re a family of high-achievers, these Nysts!

On his return from Europe, Nyst set up his own firm in Southport with his old high schoolmate from Brisbane’s Villanova College, Steve Amundsen. They later joined forces with John Witheriff, who would become one of the Gold Coast’s most respected and influential business figures, to form Witheriff Nyst.

He began acting for Abbott, whose case Nyst describes as ‘tragic’.

“There’s no doubt he was completely the author of his own demise but he has done his time – much of it in solitary confinement – and should have been paroled years ago,” he said.

Referring to political embarrassment over Abbott’s high-profile prison escapes, Nyst says: “His case went to a place it should never have gone because of politics.”

Abbott has now been behind bars so long that Brendan Nyst, a mere boy when the Postcard Bandit was first incarcerated, is now representing him in his latest parole bid.

Chris Nyst acted for both cops and crooks at the late 1980s Fitzgerald Inquiry and for the National Freedom Council in an investigation into the infamous 1973 Whisky Au Go Go nightclub bombing in Brisbane in which 15 people died.

Police ‘verballing’ (attributing damaging false statements to crime suspects) was commonplace in the era and while convicted Whisky Au Go Go bomber James Finch would would go on to confess, the NFC investigation led to compulsory tape-recordings of police records of interview.

In the late 1990s, Nyst’s legal career reached a seminal fork in the road.

Witheriff Nyst had been swallowed up by international law firm Minter Ellison, which specialises in corporate work as opposed to criminal law. There were rumblings from the firm’s Melbourne-based senior partners about Nyst’s continued involvement in criminal cases, especially when they learned he was doing pro bono work for Brenden Abbott at a time when Minters major clients included banks the Postcard Bandit had robbed.

“We were the only Minters office that did any crime and even though I tried to discourage it, the crime (clients) just continued to follow me,” Nyst recalls.

“It eventually came to the stage where Minters wanted me to stop doing criminal work altogether. I had 70 or 80 criminal clients and what was I going to say to all those people? Go somewhere else?

“I just didn’t think I wanted to do that so, although it was a bit traumatic at the time, I decided to go my own way.”

In 2001, Nyst set up Nyst Legal with a group of young gun lawyers including Jason Murakami, a former journalist, talented artist and film buff. Together with Murakami, who now works in Sydney, Nyst formed the Griffith University Innocence Project, where law students analyse DNA and other evidence to try to free wrongly-convicted prisoners. Nyst is also an an adjunct law professor at the university.

Nyst says his passion for criminal law probably has its genesis even further back than his days watching Dan Casey at his eloquent best.

“I come from a family who were basically refugees from Fascism and individual rights are very important to me,” he says.

“Post-World War II, a lot of people were very aware of the importance of defending people’s rights.”

Fused with his interest in social justice is a love of characters, of which there are no shortage in what Nyst calls ‘the criminal milieu’.

“I enjoy dealing with people and I’m a great people-watcher,” he says.

“I’m fascinated by characters and many of my clients have been great characters, especially the old-school crooks.

“Many of them are very colourful, funny people who come from humble circumstances, and are just trying to improve their circumstances through dodgy dealings.”

Some of his more memorable colourful clients have included Peter Foster (‘a repeat customer, always up to something, and pretty entertaining’) and an old pickpocket nicknamed ‘Sparrow’ who wanted to sue police because they wouldn’t let him ply his trade at the Brisbane races.

“He’d come up from NSW where he gave the cops a sling to turn a blind eye and he thought the same arrangement applied up here,” Nyst says with a chuckle.

“He got pinched and was not happy. He wanted to sue the police for breach of contract.”

It’s these sort of characters who are fertile ground for Nyst’s crime novels and films.

The release of his debut novel, ‘Cop This’, in 1999, saw him acclaimed by Bulletin/Newsweek magazine as ‘Australia’s John Grisham’. His second novel “Gone” was short-listed for the Queensland Premier’s Literary Awards and his third novel “Crook as Rookwood” won the 2006 Ned Kelly Award, Australia’s leading accolade for crime fiction.

His films have tended to the black comedy genre in the style of Guy Ritchie’s crime caper, Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels and Snatch, laden with likeable rogues and plenty of fast-paced, freeze-frame action and humorous street jargon.

His first film, 2003’s ‘Gettin Square’ which starred David Wenham and Sam Worthington, won multiple awards including an Australian Film Institute Best Actor gong for Wenham.

Nyst’s second movie, Crooked Business in 2008, didn’t achieve the same box office success but won critical acclaim from reviewers including Urban Cinefile’s Louise Keller who opined that the film ‘grabs us by the scruff of our neck and takes us deep into a murky world full of scallywags, tough guys and seriously crazed crims who bumble, tumble and shoot their way through hell and high water’. Crooked Business featured a then little-known Firass Dirani, before he went on to star in Underbelly – The Golden Mile and House Husbands, and win the Logie for most outstanding new talent.

Nyst, who formed his own entertainment company in 2006, has another crime comedy in development which he hopes to film next year and is also working on a ‘cracker of a script’ for a movie based on the Australian horse racing’s biggest scandal, the Fine Cotton affair.

“Three people also want me to do TV script outlines, so it’s busy times,” he says.

“I’ve also got a law firm to run, and that’s really what pays the bills. It’s so hard to put (movie) deals together because Australia is such a small market. You need the cast to attract any sort of decent budget.

“If I had my time over again and wound back the clock 20 or 30 years, I’d probably start writing for international markets, but I write about what I know and like, and that’s Australian stories and characters.”

Many of the characters in his books and films, Nyst admits, are based on real-life clients and events. He has been approached by both police and villains who recognised glimpses of themselves in his works.

“After Cop This came out, I had a visit from a couple of old-time underworld figures – I’m talking serious people – who wanted to know where I was going with this whole story,” he said.

“I think they thought I might have been trying to get some sort of Royal Commission or something going, Of course, I told them it was just a work of complete fiction.”

Lawyers often are pilloried for representing murderers, rapists and child molesters but Nyst says while he has had his suspicions about the culpability of some clients, he can’t recall ever having one confess to having done the crime and telling him to get them off.

“Everyone is entitled to the presumption of innocence and it’s the job of the Crown to prove guilt beyond reasonable doubt,” he says.

“You could not ethically put a self-confessed guilty client in the witness box and get them to perjure themselves by saying they didn’t do it.

“A lot of what we do is about trying to get the best possible result available and that quite often means a guilty plea. My job is to keep you out of jail but if you have to go to jail, it’s to ensure you spend the least possible time in there.”

Like a church confessional, the lawyer-client relationship is a privileged one and Nyst says he has heard his share of secrets, including respectable married businessmen charged with sex crimes who have ‘come out’ as homosexuals.

“They were leading double lives,” he says.

“I get told a lot of things about people’s lives that aren’t necessarily germane to the case and is sometimes really personal stuff. But a big part of the job is trying to take a really bad set of circumstances and make the best of it for our client.

“When I get a client who is guilty of a crime, I give them a glass of milk and a sandwich and tell them to sit down with a piece of paper and a pen and tell me everything about them.

“I want to know their life story because it’s only when you get inside people’s heads that you get an understanding of where they’re coming from, and perhaps therefore what they’ve done.

“You can never make a judge or magistrate understand your client unless you know first what makes them tick.

“You mightn’t be able to excuse some of the bad things they’ve done but it might help explain them.”