COVER STORY

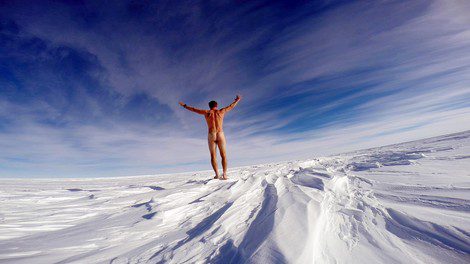

Breaking the ICE! Pink Polar Expedition – survival against the odds

WORDS: PHOTOGRAPHY

The will to survive is a powerful and curious beast – I learned that just four days into my attempt to become the first Australian to cross Antarctica solo and unsupported.

As bad luck would have it, I found myself battling one of the fiercest storms that had slammed into an Antarctic summer in 50 years. In all my years of adventuring I’d never encountered – or even imagined – such unforgiving ferocity.

Nor had I felt such terror. For three days and 12 particularly horrendous hours I knew I was totally out of my depth as the below-freezing blizzard howled its relentless challenge: die or survive.

I remember the sounds as much as the fear but, thankfully, one raged louder than the storm. It was the voice in my head that kept telling me I wasn’t going to be the guy who died alone on the white ice strapped to a pair of bright pink boobs!

If I became that guy, I’d turn the Pink Polar Expedition from an adventure to a comedy … and, worse, I’d be involving everyone who’d supported me in the farce.

A canvas of faces flashed through my mind giving weight to the voice: my wonderful wife and three gorgeous children, Glenn McGrath and the team at the McGrath Foundation, my mates … the women and families I’d met going through breast cancer. They were all good people – none of them deserved to be associated with an idiot who’d died just four days into his attempt to cross one of the world’s most unforgiving landscapes dragging a pink ‘boobsled’.

And that’s the intriguing nature of survival. Perhaps it’s not so much about self-preservation but about preserving the integrity of others. Maybe it’s more about the respect you hold for the people that cross your life path, rather than your own pride.

It doesn’t matter now – I survived and so did the integrity of the Pink Polar Expedition and everyone who supported it. But that notion of the power of being motivated by others has stayed with me. It’s a theme I explore in the corporate talks I’ve given since returning from Antarctica – and it resonates. The feedback I’ve received from those talks reinforces the notion that every business has storms to battle but those that have a cause beyond the bottom line don’t just survive, they flourish. And the people involved with those businesses tell me they’re more fulfilled.

It’s the same in life: we all have our own storms to battle and, whatever the motivation to survive, the trick is taking things from them that enrich our lives. That literal storm in Antarctica was a real crossroad for me – surviving it gave me an incredible faith in my ability to make the right decisions … then and now.

You may have heard about the storm – it was the one that delayed Prince Harry and the Walking with The Wounded Antarctic expedition. While they were holed up in a hotel in Capetown, I was bunkered down in my tent, but living in a strange kind of luxury – the knowledge that I’d prepared to the best of my ability, that I’d given myself the best shot at survival.

I’d trained on glaciers in New Zealand and crevasse fields in the Arctic. Back home on the Gold Coast in Queensland, I’d hauled tractor tyres through the soft sand of my local beach and up the wooded hills of Currumbin Valley. I’d gorged myself on an unfamiliar diet of junk food to fatten up for the inevitable weight loss (which incidentally turned out to be 22kg).

And I’d upskilled, seeking out the advice of the world’s leading polar experts including Borge Orsland, the Norwegian explorer who held the speed record I was attempting to beat. Remembering my first conversation with Borge evoked a wry smile as the storm battered my tent. I’d rung him to tell him I was challenging his record and to ask for his help. I could almost hear his smile down the phone line – I’m sure he thought an Aussie from the beaches who’d never skied before posed no threat at all! Sadly for me, at that point on the ice, his record was looking pretty safe indeed.

Still, I did have a chuckle remembering the conversation. My sense of humour may have been black but it was still in tact – and, so was my tent. Researching the right equipment was critical to my preparation. So far the tent was holding (thank you Wild Earth) but I knew if it failed, death by exposure was certain. That instinct to survive kicked in and ironically it was the bright pink ‘boobsled’ that came to my rescue – I used it as a fortress, digging into the ice and snow and embedding it as a buffer against the gale-force winds.

During those three stormy days, I rebuilt my ‘boobsled’ wall on too many occasions to remember, not just because it was my literal ‘buffer against the storm’ but also because my trusty tent was constantly becoming buried in a sea of life-threatening white.

In between these times I lived another cliché: waiting out the storm.

Fear and loneliness stalk you like wolves on any solo journey – one on either side of you. You have to keep them at bay or they feed on your confidence. In Antarctica on Day 4 of the Pink Polar Expedition, it seemed they also wanted to take shelter from the storm and crowd my wind-blown tent. It took all my resolve to shoo them away – I knew I had the physical strength to battle the storm but I also had to believe I had the mental fortitude. On day seven, the storm abated and I continued my journey in the knowledge that my life had shifted forever because I’d learned yet another cliché rings true: the storm really does maketh the man.

There were many challenges on the 53-day crossing that required me to muster mental power. In fact they started on day one when the doors of the Ilyushin aeroplane opened and the blast of frigid air hit my lungs, along with a sense of panic as I realised that once I stepped off that plane there was no warmth until I’d reached the other side of the continent.

Another was the Somo Veken Glacier – deep snow, steep slope. And, I had to climb it – twice! I had two supply sleds, weighing 180kg in total, and I couldn’t climb the glacier with both of them so I had to split the load, covering step by terribly small step once … and then again.

There was also the crevasse field: mile after mile of tension knowing that one wrong decision would see the heavy sleds pull me through the ice in a moment.

Falls were pretty much a daily occurrence, but one accident brought my only other truly near-death experience on the ice. My methods of travel were trekking, skiing and kiting and, on this occasion, I lost my nine-metre kite. On another, my kite harness exposed my stomach to the elements resulting in a nasty rump steak-sized frostbite that I had to manage for the majority of the journey.

One of my worst days started out as one of my best: the wind was pumping and I was making great mileage until I stopped and realised my food sled had flipped and split open, scattering my meager supplies on the ice. I trekked back eight kilometres to rescue what I could but I’d lost a lot … and was totally out of food by the time my journey ended.

The doldrums hit often and the wind-less days were really hard to deal with, particularly just before Christmas when there wasn’t a breath and I was stranded just kilometres from the South Pole. When I finally reached the Pole, I was only at the two-thirds point of the crossing and it took all my resolve to leave here and keep going … but I’ll forever be pleased I did because for every bad moment on the ice there was an equally rewarding one.

In contrast to the horrid sounds of that first storm, there was the incredible sound of Antarctica’s silence. The days of doldrums were a nightmare but the days of wonderful wind were a dream as I flew across the ice, feeling the freedom of a bird. The glacier was tough but reaching the plateau was a joy. The lost food was a worry, but my first meal after finishing the crossing (steak and trifle!) was the best I’ve ever had. And, I can’t ever remember a beer tasting so good!

All of this started with a dream: to raise breast awareness and funds for the McGrath Foundation. If dragging that crazy pink ‘boobsled’ across the ice prompted one person to have a breast check, it was all worth it! And, we managed to raise nearly $250,000 for the McGrath Foundation. At the end of the day that’s what this was all about … but I’m pretty proud that we managed to beat a few records in the process.

Since returning home as well as joining the speaking circuit, I’ve been continuing my veterinarian work and planning itineraries for expeditions to New Zealand, the Amazon, Africa and Antarctica through my 5th Element Expeditions company. I’d love you to join me on one of our expeditions down the track but, for now, I leave you with two thoughts: The first is one of my favourite mantras – “never forget to dream”; The second is a quote from T.S. Elliott: “Only those who will risk going too far can possibly find out how far one can go”.