LEGAL

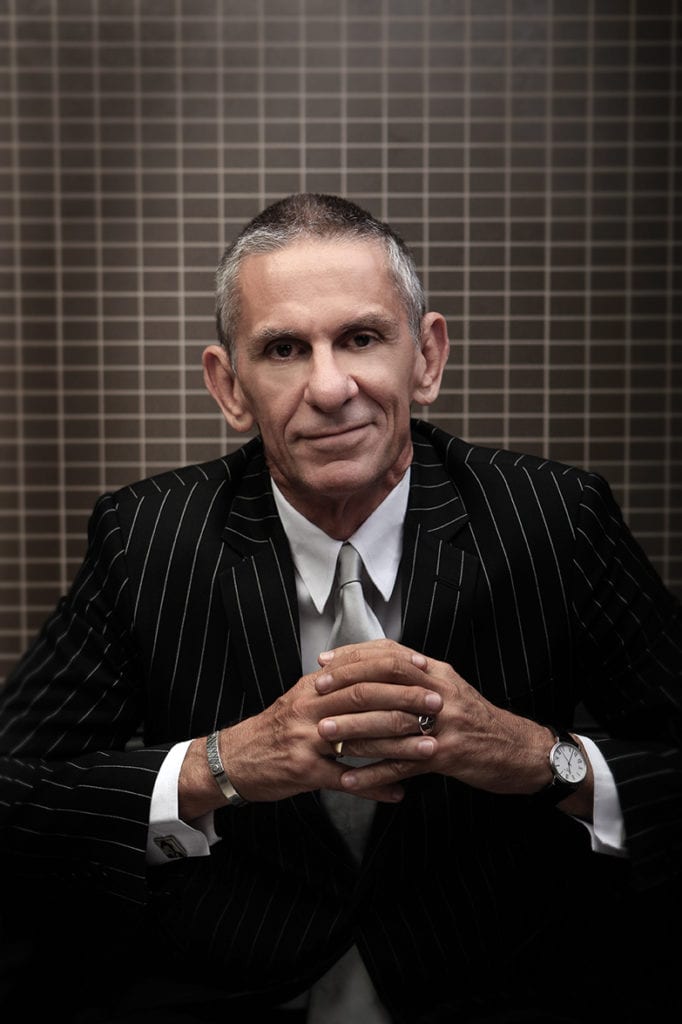

Body Heat

WORDS: Chris Nyst PHOTOGRAPHY Portrait - Brian Usher

When I first started practising law, ‘verbal’ was a dirty word. It referred to the then-widespread police practice of untruthfully asserting a suspect had verbally confessed to a crime they were charged with. To ‘verbal someone’, or to ‘drop a brick’ on them, involved swearing on oath they had admitted their guilt when they hadn’t and therefore involved police fabrication of evidence and perjury.

Not surprisingly, while ‘the verbal’ was an open secret muttered surreptitiously in backstreets and hotel bars, it was strictly forbidden to be spoken of openly unless you were looking for trouble. When defence lawyers alleged it to any police witness in court, it was roundly denied – and that denial firmly corroborated by a procession of fellow police officers.

Until the Fitzgerald Inquiry in the late 1980s, the official line was that ‘the verbal’ was nothing but a scurrilous myth perpetrated by gullible lawyers and their lying clients.

One old Sydney knockabout – admittedly a man of questionable credibility – once told me how he was first introduced to the practice of verballing. He said he had been arrested and taken to an inner-city police station, where two young policemen started slapping him around, trying to get him to admit to a stealing offence.

“What do you blokes think you’re doing?” an older, more seasoned detective demanded. When he got the sheepish reply “Well, gees sarge, we’re just trying to get him to confess what he done”, the senior man scoffed disdainfully. “I know that bloke,” he shot back at them. “You’re not going to bash a confession out of him. He wouldn’t tell the dentist what tooth to pull.”

The sergeant then loaded up a typewriter with paper and carbon sheets. “You’re just hurting your hands belting that bloke,” he added, as he tapped away on the keys. “I’ll show you how to do it.”

He then proceeded to type out a full and informative interview with the silent suspect, in which he allegedly provided a full confession to the offence. Then the sergeant finished it off by typing one question. “Q: Are you willing to now sign this record of interview?” followed by the simple answer. “A: No, I never sign anything.” And that was it. A legally admissible, unsigned Record of Interview.

Until relatively recent times, unsigned and otherwise uncorroborated confessions were admissible in courts throughout Australia. As a result, hours of court time were spent debating what was and was not said behind closed doors in police stations around the country. Notoriously, in the murder trial that followed the infamous 1973 firebombing of the Whiskey Au Go Go nightclub in Brisbane’s Fortitude Valley – in which 15 people were killed – both accused claimed they had been ‘verballed’ with unsigned police confessions.

Their convictions fuelled a long-running and increasingly public controversy around the use of the verbal. Queensland lawyers began calling for mandatory tape-recording of all police interviews, but their calls were shouted down by the Queensland Police Union. Even when the 1976 Lucas Inquiry reported police ’planting evidence, forging warrants and fabricating confessions’ and recommended the immediate introduction of tape recorded interviews, the government stood firm.

But the controversy raged on and had gained substantial momentum by 1987, when then top Brisbane QC, Tony Fitzgerald, was appointed to head up the Commission of Inquiry into Possible Illegal Activities and Associated Police Misconduct. A year later, with daily revelations of serious police corruption flying thick and fast in the Fitzgerald Inquiry, I was retained by the National Freedom Council to petition the government to convene a Royal Commission into the use of allegedly fabricated confessional evidence at the Whiskey Au Go Go trial. As that push was gathering momentum, the government announced new legislation requiring all police confessions to be tape-recorded.

The effect was immediate and game changing. Old-guard police who once lazily relied on confessions were suddenly forced to roll up their sleeves and do the hard work and the new-guard learned to be better detectives, investigators and police. Endless hours of court time – once spent working out who really said what to whom and why – were saved overnight and honest police were spared unfair assertions of impropriety. Police who had resisted the reform for decades suddenly found recorded interviews changed their lives for the better.

Wind the clock forward 30 years. Body-worn cameras are now standard issue for police throughout the country. They are capable of providing a very useful, if not foolproof, account of all interaction with suspects arrested and charged with offences.

Yet, for some reason, the use of BWCs is not mandatory, or even regulated in any reliable way. Police can deactivate their BWC whenever they like, edit the footage before a court case and limit suspects’ access to the footage. So, while BWC footage is regularly produced in court to advance a police prosecution, it is often sadly missing where it might have assisted the defence.

Earlier this year, when NRL star Curtis Scott was charged with a string of offences, including assaulting two police officers, his lawyers were fortuitously able to access BWC footage which showed he was in fact fast asleep under a tree the whole time. The vision showed him being handcuffed, tasered and capsicum-sprayed before regaining consciousness. In a recent unlawful arrest case, the Queensland Supreme Court was told the arresting officer’s BWC was switched off when consent to a search was allegedly given, and in examining assault allegations at the Grevillea Youth Justice unit, Victoria’s Children’s Commissioner was told ‘body-worn cameras were not operative’ during the time of the alleged assault.

This is 2020, folks. We have the technology. Isn’t it time to make police interaction with suspects – warts and all – a matter of provable record?