BOATING & FISHING

A Night of Terror

WORDS: Shane Watson PHOTOGRAPHY Photographs: John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland photographers - Mr E H Foreman and Mr George Jackman, City of Gold Coast Local Studies Library

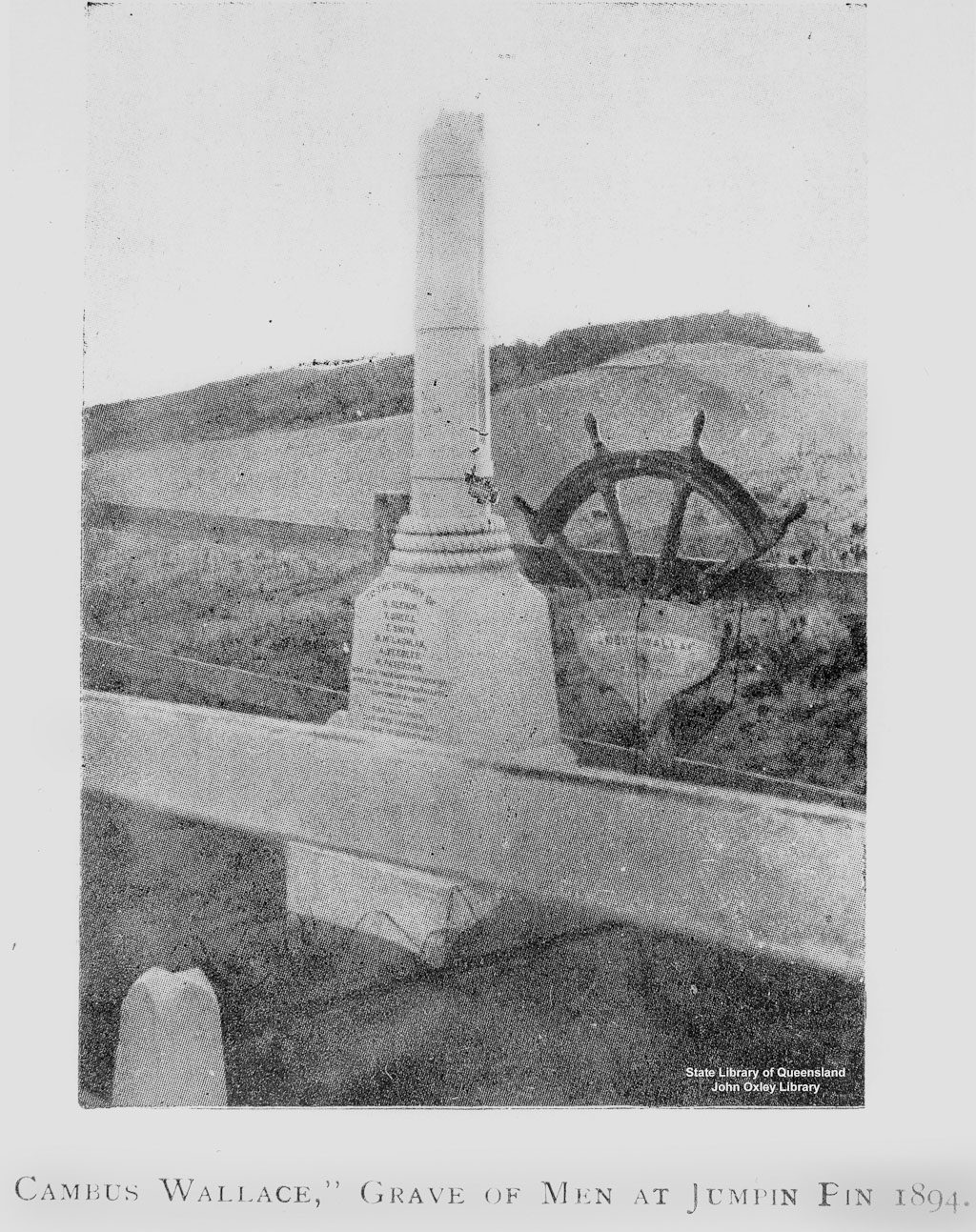

Perhaps one of the shortest nautical stories ever chronicled – four months from maiden voyage to total shipwreck – the Cambus Wallace was wrecked 121 years ago (3 September, 1894) where North and South Stradbroke islands then met.

Pumpin Pin

Dawn begins to break the darkness to the east of Stradbroke Island but the light can’t come soon enough for the stricken seamen of the Cambus Wallace, whose only focus for three hours now has been firmly fixed on staying alive.

Monster waves and fierce squalls create a terrifying and indescribable noise as the ill-fated iron barque is mercilessly ripped apart in a “boiling pot of seething foam” – the crew long ago sought refuge on the poop as angry waves swept the entire length of the main deck.

The main mast of steel had cracked and broken within 30 minutes of the vessel being dumped onto the second beach break, her entire keel of over 200ft smashing on the soft and swirling sand and her lengthy upper part falling toward her bow.

The absence of panic among the hardened sailors strikes “The Old Man”, 27-year-old Captain W. A. Leggat. Some have opted to climb into the riggings to wait for morning.

Just the steward calmly returns to his cabin to wait for rescue and laughs when told to hurry – his body was among five found the next day on the beach. The starboard lifeboat is dangled in the davits, smashed and useless.

Yet another boat is stove in on the same side, so the port-cutter is prepared for launching.

The barque lists heavily to starboard and soon … it’s clear nothing can be done.

Capt Leggat calls for volunteers to run a line the few hundred metres to the beach and two brave souls step forward – the strong-swimming Swede Gustav Kindmark and Jack Reid.

Carrying the hopes of their fellow crewmen – and the heavy, wet rope – they courageously face the sea’s fury head-on.

By the time an exhausted Kindmark makes it to shore, Reid is back on board, reeled in clinging desperately to the lifeline but, nevertheless, still breathing.

Some 40 years later, historian Thomas Welsby wrote in the Brisbane Courier (22 July 1933): “No others would dare the swim, even though it was less than a couple of hundred yards in distance. Heavier seas, as the tide rose, now broke open the hatches, and tons of cargo was washed overboard towards the beach.

“At noon the mate was washed overboard, but managed to reach the shore. Others dived and made the land. As the afternoon began to wane, another attempt at launching a boat was made.

“The carpenter was washed from the tackle and drowned; the cook jumped from the rigging and met a similar fate.

“Then as the day closed and darkness was again coming on, the wind lulled.

“Within 18 hours, the Cambus Wallace had almost disappeared beneath the water, and 22 sailors lay ashore famished and almost nude, with five of their recent companions lifeless near the sand dunes.”

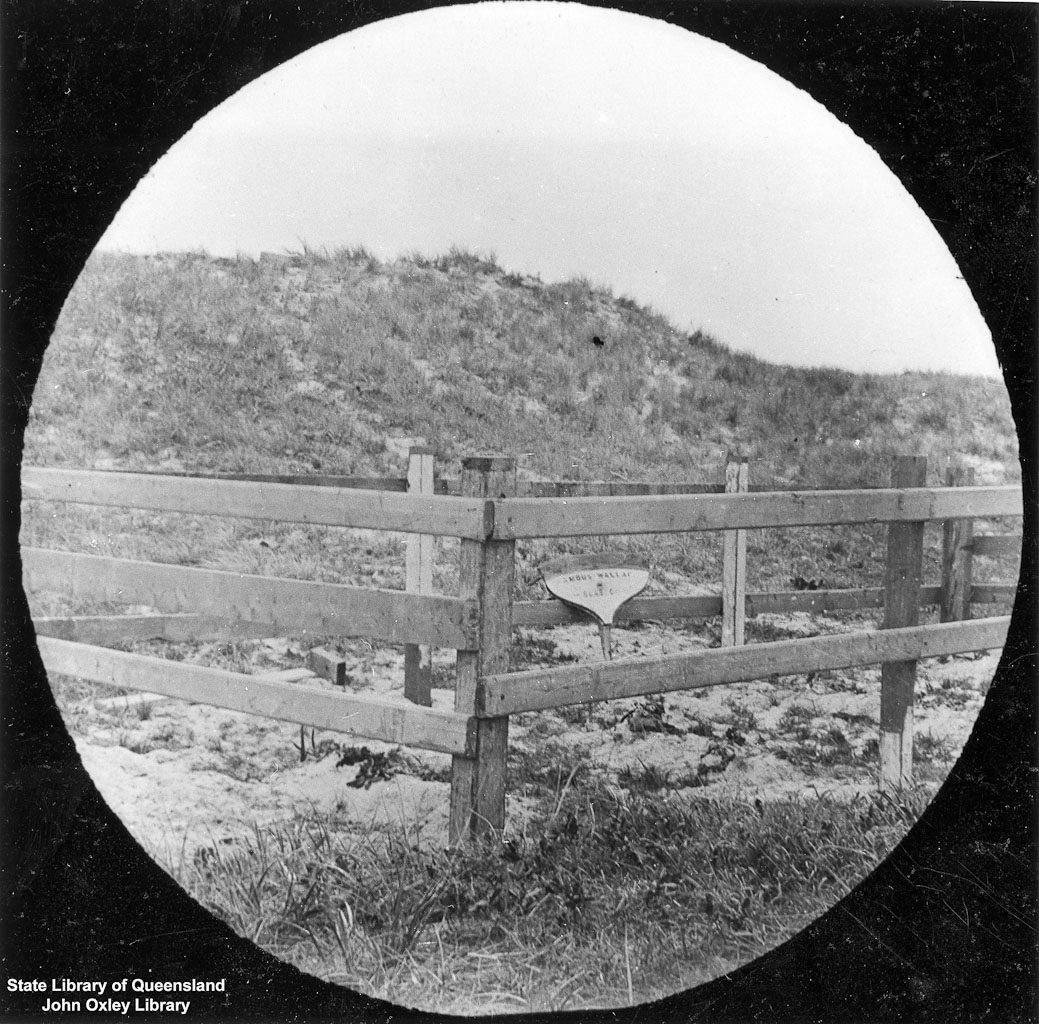

The dead were buried on a sandy hilltop at Jumpin Pin, overlooking the ocean. Welsby records: “Two pandanus trees gave them shade, but not for very long. Before four years had passed the Pacific arose in one of its terrific moods, washed over these hilltops, broke through the island and took its fury into Swan Bay. With it passed these sailors, their resting place being transferred to the deep sea.”

A “weak and injured” sixth sailor died after rescue and was buried at Toowong Cemetery.

Beer, whiskey and dynamite

To some, a shipload of beer and whiskey mixed liberally with a mountain of explosives might sound just like the ingredients needed for one heck of a party… or in the case of Stradbroke Island, some could claim it was a recipe for disaster.

Historical records state that the government of the day, concerned about the safety of the local fishing industry, decided to detonate the large mound of dynamite which never made it to the Queensland gold mines.

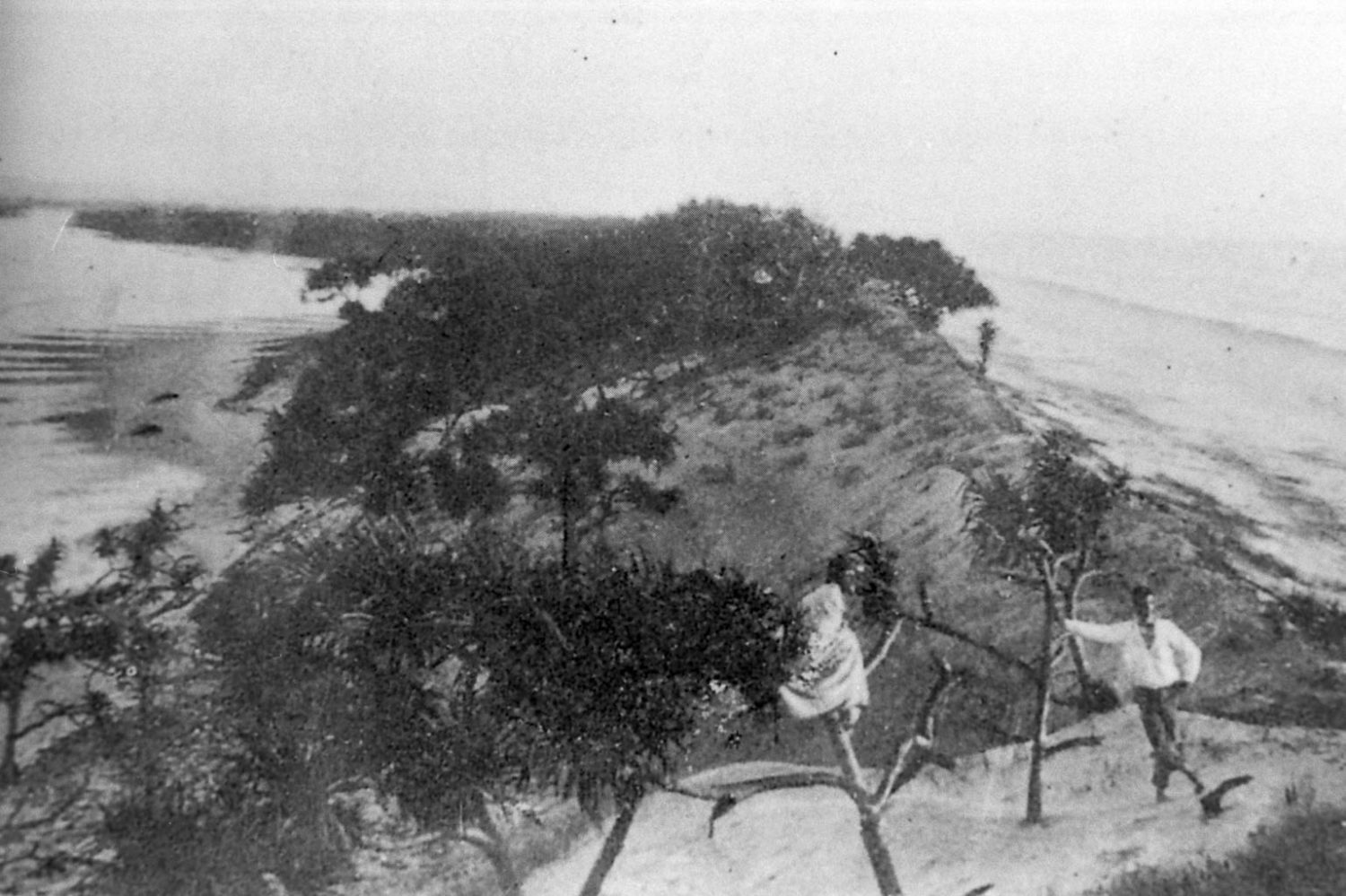

However, it seems the blast was far bigger than anyone thought possible, causing the collapse of the black honeycomb sand foundations and creating huge holes in the dunes in the narrow area of Swan Bay.

The massive explosion was even heard in Brisbane.

Some say it would have eventually happened even without the blast … but the break-through at Jumpin Pin occurred about four years later when another Mother Nature once again lost her temper.

Alone on the beach

Face down in the sand after an exhausting swim to shore, Gustav Kindmark knows he must rise above his fatigue if there is to be any hope for his stricken fellow seamen.

The strong-swimming Swede was the first to make it to land in a brave bid to secure a lifeline but had lost his grip as he was smashed by the relentless waves.

He does not know the fate of Reid, who had jumped into the water with him.

Kindmark staggers to his feet, scours his unfamiliar surrounds and is startled at how quickly the barque is breaking up – he decides to head south, where instinct tells him he is sure to find civilisation.

Historian Thomas Welsby records in the Brisbane Courier: “He soon came to Currigee, not far from Jumpin Pin. There the sailor told his sad story. Kind-hearted oyster men, coloured men as well as white, were soon back at the scene of the wreck.”

Author Garry Hardgreaves, in The Wreck of the Cambus Wallace, suggests Kindmark set off in search of help and finally made out the silhouette of Jim O’Connell riding up the beach on horseback. Unable to understand the Swede, O’Connell took him back to Currigee oyster camp where he collapsed, and was left to rest for the best part of a day before being taken to the Pacific Hotel at Southport where one of the drinkers, Will Hanlon, translated the dire situation and sought out the local police sergeant, who alerted the Brisbane Portmaster.

The next morning, Hardgreaves writes, Hanlon and O’Connell took Kindmark back to the wreck … where they found that same police sergeant perched under a pandanus tree, in an obvious state of intoxication.

When Hanlon asked the policeman if he had any water he had replied: “No, but come up, my boy … there’s lashin’s of grog for the taking of it”.

According to Hardgreaves, the oyster farmers were also pilfering the cargo … “conveying numerous quarts of Burkes Whisky into the scrub”.

Perhaps Welsby puts it more succinctly: “The outer shores of Stradbroke were thickly strewn with every class of merchandise, and became an unbonded warehouse for any and everybody … much “perishable” cargo disappeared, even before the eyes of the Customs officers … probably some who read this may have participated in the salvage, and will appreciate what I purposely will leave unwritten …

‘verbum sapienti sat est’.”

verbum sapienti sat est – Latin: “a word to the wise is sufficient”.

FAST FACT…

Jumpin Pin – “big fellow wave”